By Phoebe Mackie, Third Year English

We are all familiar with a certain stereotyped trope in war films; the young Western male who goes off to fight in France with lofty patriotic ideals. I’m talking about Desmond T. Doss in Hacksaw Ridge, Lance Corporal William in 1917, and Saving Private Ryan, to name a few. But in these movies, there is a narrative which has been lost, stories which have fallen through the cracks. That is the narrative of British colonial subjects, 2,350,000 from Africa alone, who were brought from their homeland to fight in World War One. This is the story John Akomfrah is determined to tell in his film Mimesis, currently showing at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.

Mimesis is a collation of footage from the World War One archives interspersed with a modern retelling of individual African soldiers' experiences. Just as British troops went into World War One with naïve patriotic ideas and romanticised notions of war, Akomfrah aims to capture the less conventional narrative of the British colonial subjects and their trust in the British empire turning into disappointment as they entered the Western front.

Akomfrah effectively contrasts the deeply intimate with the impersonal. The intimate modern retelling of men from all over Africa leaving their wives and mothers at home, then travelling to Europe by boat, and finally contemplating the vast death and devastation that they encounter there is thoughtful and beautifully framed. This image, contrasted with the real footage of Africans working alongside white Europeans at wartime jobs reminds the viewer of the enormous scale of the war, and consequently the disregard for the individual.

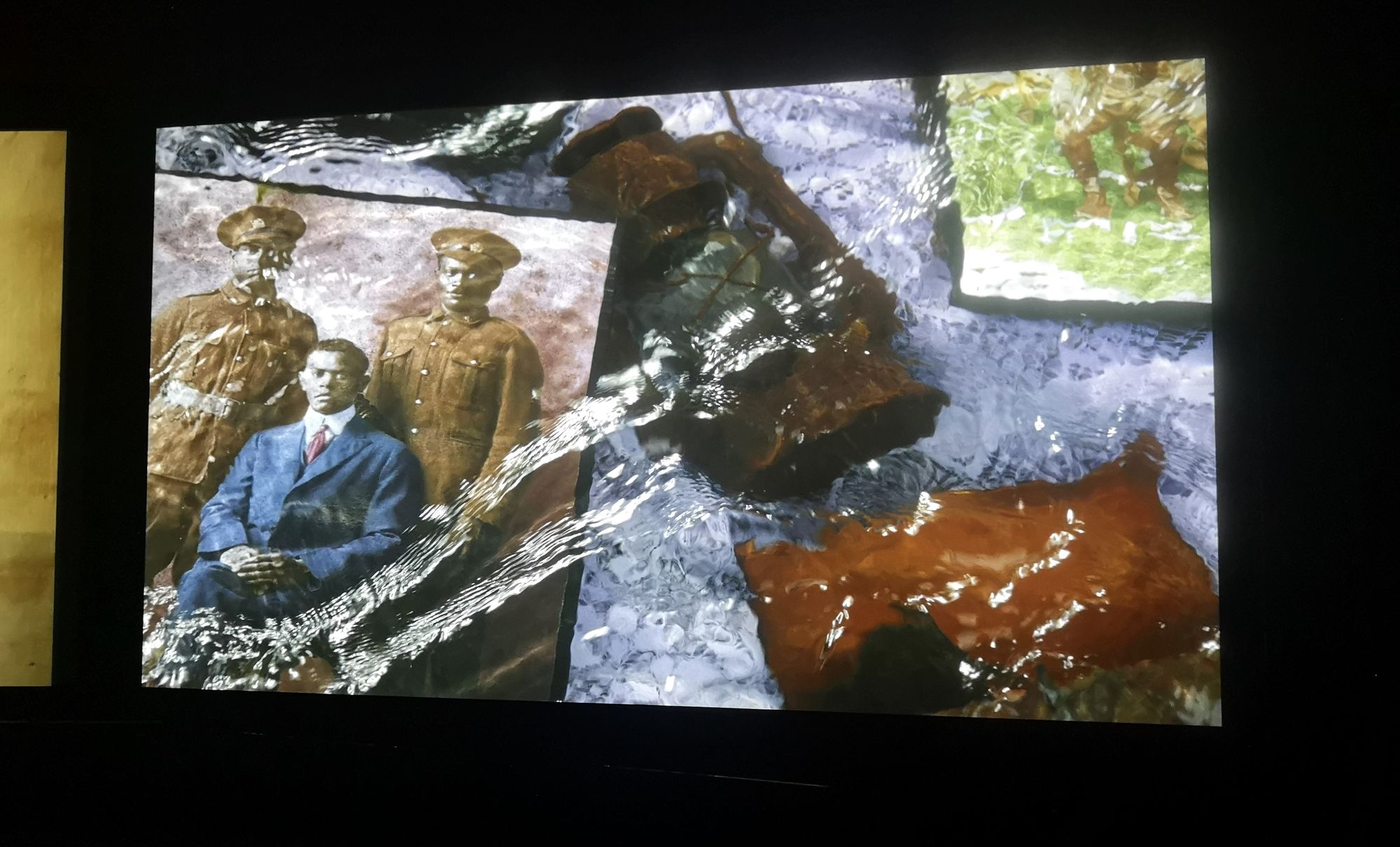

The film takes the viewer on a chronological journey of the Africans who travel from their homes to France, segmented by black and white original footage. Throughout this, Akomfrah uses water in a striking and unusual way. One of the opening scenes which recurs throughout is of a collection of African soldiers’ belongings, such as a photograph, a blanket, and an instrument with water running over it. Left wondering the significance of these objects, I found this imagery of water not only gave an extraordinarily beautiful effect but left a sense of ambiguity. Are they the objects brought with the African men to France and then tossed into a lake after their death? Or are they meant more metaphorically as a collation of tangible objects that made up their lives, to highlight the pitiful sadness of what is left of them after they’re gone?

Akomfrah plays with the conventional single-screen movie experience by having not one but three large rectangular screens, all depicting something slightly different at any one time. There are moments when the screens have totally different scenes on them, one in black and white from 1917 and another in colour and from the 21st century. Other times the screens show the same scene but one from a different angle, or one happening a few moments before the other. Initially, I found Akomfrah’s use of time and space incredibly disorientating as my eyes constantly moved from one screen to another, anxious not to miss anything. But as the film progressed, I got the sense that that was Akomfrah’s indented effect; he demonstrates a beautifully playful relationship with time.

The end of the film lost some of the beautiful ambiguity and sensitivity that the rest of the film had. Near the end, the film showed the African soldiers back in Africa each in turn sitting on chairs and being “shot”. To me, this felt staged and so obviously constructed that it took on an artificial tone. Then the “dead” men each entered a modern room filled with objects and lit by LED lights. This to me made the film take on a slightly bizarre, futuristic, other-worldly tone which contrasted too heavily with the subtle realism of the rest of the film. For me, the message was strongest when Akomfrah left the viewer with more questions than answers.

Nevertheless, Akomfrah's film is stunningly beautiful and deeply thought-provoking. I came out of the film not only moved but angry that these are the stories which have been totally disregarded by the Western narrative of World War One. I suspect that was precisely Akomfrah’s intention.

Mimesis: African Soldier runs from 1 October – 8 January at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery.

Featured Image: Courtesy of Milan Perera

How did Akomfrah's Mimesis make you feel?