By Ellen Jones, Second Year, Politics and International Relations

We’re rarely more aware of the world around us than at the start of a new season, when that world begins to change. Though British spring tends to drag its heels, it’s the littlest things—flowers knuckling up through the earth, or a patch of blue sky—that announce its arrival in a cycle far bigger than us. With that in mind, here are three reads to take into the brighter, longer days of a new season.

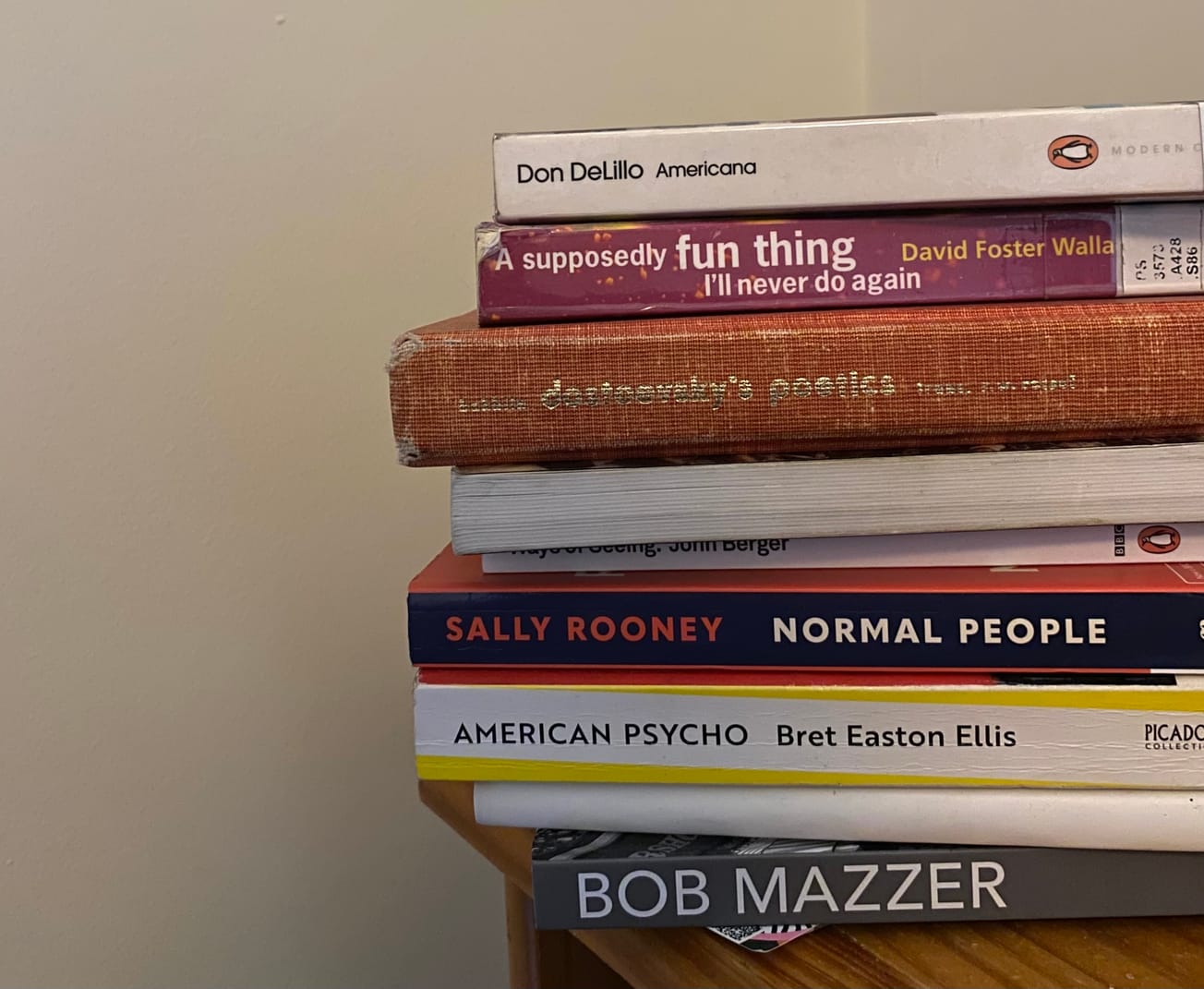

New and Selected Poems, Mary Oliver.

Mary Oliver’s poems capture the physical touches of the changing seasons, in all their delicate beauty. The attention her works give the natural world, following it through its death in autumn and winter, into its rebirth in spring and summer—there is a poem for every season in this collection, with my personal favourite being the poem, Wild Geese. Oliver’s reflections in Spring Azures, Peonies and Blossom are as gently lovely as the flowers she describes.

Poetry collections can be tricky to approach—the instinct can be to try and tackle them page by page, like a novel, which can quickly become overwhelming. Instead, this collection of nearly 150 poems by Mary Oliver is maybe best enjoyed intermittently, dipped in and out of every so often over a cup of tea, or opened to a random page. Her poems look at natural landscapes over the changing seasons, but also our place as animals that can often feel so disconnected from these landscapes; in her words, she ‘announces our place in the family of things’.

Foster, Claire Keegan.

Few authors treat the little things with quite the affection and care that Claire Keegan does. At just under ninety pages, Foster—like much of Keegan’s work—is a novella that can be read in one day; it follows a young girl in rural Ireland, being taken from her crowded family to stay with her relatives, the Kinsellas, on their farm for the summer, as her mother prepares to have another baby. Shy at first, the girl’s relationship with the Kinsellas gradually grows into a fond new attachment—the only limit is the summer, which must eventually end.

A tender story of family, childhood and secrets, the concise and subtle style of Keegan’s prose lends a captivating weight to each and every sentence, and allows the smallest everyday details—a jar of jam, or a choc-ice—to become something more profound. Though books can be a vital source of escapism from ordinary life, into fantasy lands or distant histories, there’s something special about a book that can actually make the world we live in seem a little bit more wonderful. This is the sort of feeling that Claire Keegan’s writing gives me, and it’s the same sort of feeling I get when spring takes hold, and sun starts to show, and the trees begin to blossom.

The Archive of Alternate Endings, Lindsey Drager.

The Archive of Alternate Endings focuses on the cycles that surround us in a slightly different way: rather than centring on the changing seasons, it instead revolves around the journey of Halley’s Comet, a celestial body visible from Earth every seventy-five to seventy-nine years.

Technically, the novel might come under the science-fiction header, as it tracks various instances of the comet’s movements over Earth between the years 1378 and 2365—but it doesn’t feel much like science fiction. Rather, what the comet links are several individual human stories—primarily focused on sibling relationships—taking place beneath it, across the millennium: Hansel and Gretel lost in the forest, Johannes Gutenberg and his twin, a sister and her gay brother in America in 1986.

Drager explores humans, their sexualities, their art of storytelling, and their habit of loving each other, from the vantage point of a comet fulfilling a cycle far greater than any of us. It’s a devastatingly beautiful novel, yet difficult to summarise —I’ve never read anything like it. But Halley’s comet will next be visible from earth in the year 2061: that’s over a hundred seasons that will come and go between then and now and an infinite amount of stories.

Featured image: Ella Carroll

What books have you read this month?