By Hannah Stainbank, First Year, English

The Lyra Poetry Festival entered its fifth year in 2024, with events including workshops, walking tours, readings, lectures, and slams. I was able to volunteer at Simon Armitage’s reading and Q&A, and the Grand Slam final.

Admittedly, I went into that event knowing very little about Simon Armitage, other than that he is the current poet laureate. I found that he was likeable, down to earth, and very funny, reading poems that felt tangible and alive. Hearing the poetry read by its author made for a richly immersive experience, in which it was easy to fully concentrate on and appreciate his chosen poems. The observations in his poetry are both astute and approachable, without any indication of pretentiousness. He spoke about writing poetry over lockdown, when it was becoming increasingly popular, and how this wasn’t a time to suddenly become ‘experimental’ or ‘avant garde’. He gave the sense that he writes for a purpose other than self-indulgence or expression, but rather for the widespread benefit of all who want to read his work. None of this is to say that his poetry is at all simplistic or that it endeavours to talk down to the reader (or in this case, listener), as he dislikes poetry that expects you to agree with a ‘force-fed’ point of view. Overall, I found his poems to be multidimensional, with ideas that can be universally enjoyed and related to, largely thanks to his quick, dry humour. I especially enjoyed the first poem he read, ‘Thank You for Waiting’.

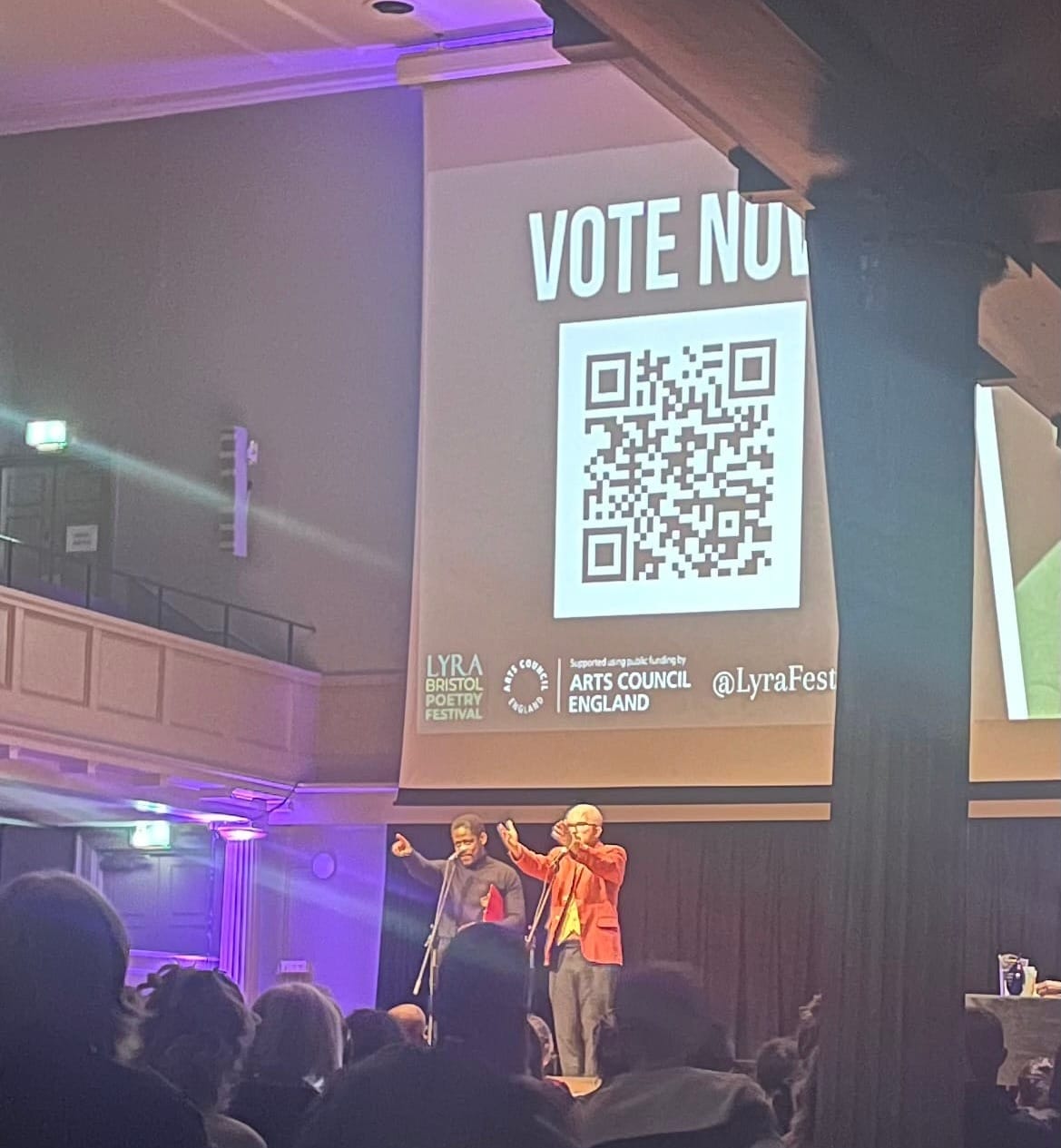

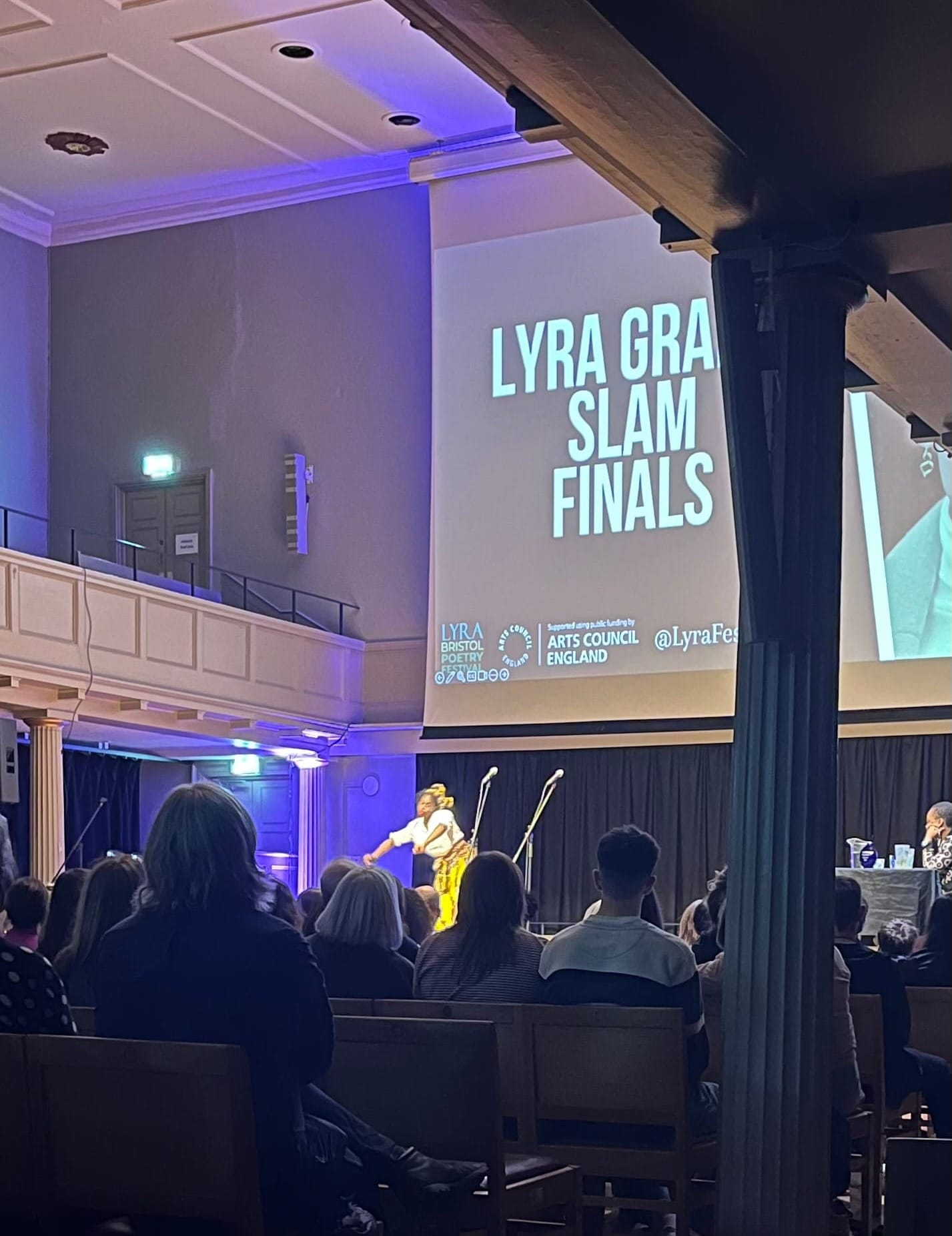

Later that evening, it was the Grand Slam Finals. The crowd was noticeably younger than Simon Armitage’s, though generally still twenty and thirty something’s rather than students. The atmosphere was lively, from the ooh’s and aah’s (described as ‘poetry digestion noises’) to clapping and stamping after each performance. There were eleven performers, all of whom had qualified previously, and they were each given three minutes for their poem. After this, the audience and judges voted on the best poets, and the top three performed a new poem each. Excitement in the room only grew as the evening continued, and as each poet had a uniquely different voice and style, it became increasingly difficult to decide on who was ‘best’ in such a subjective and deeply personal medium.

I went into the slam slightly sceptical, having never been to one before. I was wary of the popular connotations of slam poetry; I’d only ever really seen it mocked as something that is overly dramatic and, at times, a bit cringe-worthy. In general, I was pleasantly surprised. The poetry was sensitive and emotive, but also punctuated with moments of humour, and the diverse range of poets meant that I didn’t feel that my sense of ‘slam poetry’ as a whole could be pinned down to an individual style, though I did keep some of my scepticism. Firstly, at times I felt the performance aspect of it came at the expense of the poetry, with slammers increasing their pace to reflect their emotions (or to keep it under the 3 minutes), but also preventing me from being able to fully hear and register their words. That being said, I was sat at the back of a large room, so my experience is not the same as the paying audience sat in front. Also, there’s something to be said for trauma becoming a kind of currency within the slam. Poems were largely centred around various traumas and the ways in which they are experienced, with a few exceptions. It’s certainly a valuable way of raising awareness around the variety of issues and lived experiences people have, and it is powerful in eliciting a strong reaction in the audience, but it raises questions surrounding the trivialisation of trauma: listening to back-to-back three minute packages of people’s darkest thoughts and times makes it difficult to take the time and mental space necessary to fully appreciate each individual’s experience, and how they transform this experience into art. I appreciate that this medium provides catharsis for the poets and can be either relatable or enlightening to the audience, but I wonder if at times the poets feel a pressure to offer their traumas to the audience because it is a reliable way of getting a positive reaction.

However, the poem that won, by Joe Eades, focused not necessarily on trauma, but instead on the poet’s relationship to her daughter. It was emotional and tender, expressing the difficulties of motherhood and the unwelcome inevitability of letting go when both mother and daughter grow up. Another finalist explored the nature of motherhood, after being accepted into the final due to a poem about grieving her mother. Her final poem was an ode to the women that helped her throughout her adolescence, and its power was only magnified in light of her previous poem. Through coupling the two, beginning with her grief and trauma, and moving to an appreciation of the people around her, in just two poems she painted a poignant picture of how she interprets her role as a daughter. I was very grateful that she got into the finals and was able to share that second poem.

Across only two events of the festival, I was able to experience an incredible range of poetry from talented poets and up-and-comers to well established professionals. The poets were inspiring and intriguing, and I’m grateful that a festival like this exists within Bristol to make poetry accessible for all.

Featured Image: Tara Bell

Will you be attending the next Lyra Poetry Festival?