By Ella Fraser, Arts Subeditor and Melissa Braine, Arts Deputy Editor

Hosting an eclectic line-up of major writers, artists, and thinkers, Clifton Village LitFest returned for its third year on the 11th-13th November 2022. Taking place in the intimacies of Clifton Library and the Christ Church, Epigram attended heartfelt conversations with authors Lily Dunn and Kit de Waal.

Lily Dunn – Sins of my Father: a Daughter, a Cult, a Wild Unravelling

As part of Saturday’s events, Lily Dunn was warmly welcomed by members of the public in the Clifton Village library. Introduced by Professor Helen Taylor, author and lecturer of Creative writing at Bath Spa University, Dunn proceeded to effortlessly absorb everyone in the room with her touching and fascinating autobiography, Sins of My Father: a Daughter, a Cult, a Wild Unravelling.

Dunn told an autobiographical account of her childhood, focusing specifically on a troubled and seemingly unpredictable father, whom Dunn’s complex relationship with lays the basis of her heartfelt story.

Her early life, defined as an “idyllic family with a large house in London”, Dunn described as tainted by the instability of her troubled father; a successful entrepreneur and owner of a publishing company, he was haunted by unresolved emotional issues, which led him to engage in extramarital affairs.

Dunn states that this sexual deviance was a precursor to her story’s most focal event, his joining of the Bhagwan Shree Raneesh movement. The movement, which Dunn assuredly labels to be a ‘cult’, focused on eastern philosophies which played into western ideals of hedonism and self-fulfilment. Appealing to those who Dunn described as ‘bored of their mundane life’, her father decided to leave behind his family for India, and later Italy, in pursuit of these ideals.

Dunn spoke of swinging between the romance and reality of her father’s behaviour, reigniting her recollection from both angles. She describes him as ‘charismatic, beautiful and affectionate’, but capable of ‘narcissistic destruction’ that left her in a ‘suspended state of longing in his absence’.

The contrast of her two perspectives played out between her home-life in London and chaotic summerly visits to her father’s commune in Tuscany. She recalls a passage of her book, when at the commune she was urged at 13 to have sex with one of her father’s friends. Dunn humorously defends her father, as he withdrew his suggestion upon finding his friend’s gonorrhoea tablets.

Just had an amazing event at Clifton Literary Festival talking about #SinsOfMyFather and some excellent interviewing from @rushton67 - a big audience too! On this beautiful sunny autumn day #memoir #WritingCommmunity pic.twitter.com/9HLfseF7fG

— Lily Dunn (@Lilydunnwriter) November 12, 2022

What I found to be most intriguing was Dunn’s self-reflection on her experience of Jungian psychoanalysis; the idea of her father’s world reflecting the shadow self, and her inner turmoil of wanting to submerge in his hedonistic reality. She spoke of her experience of Jungian psychotherapy as a guide to understanding her father as an archetype, helping her to objectify her experience.

It is this reflection, it seems, that has led her to transmit this story with such positivity and grace. When queried by an audience member as to whether she had forgiven him, she answered firmly “I don’t think I have to forgive him. It is the landscape of my upbringing. It has served me and my creativity.”

Dunn recognised the book to be exactly what she envisioned, conveyed by the earnest and impassioned tone she maintained throughout the entire talk. She was received by a calm and receptive audience, most of whom felt comfortable in connecting to her story both silently and vocally.

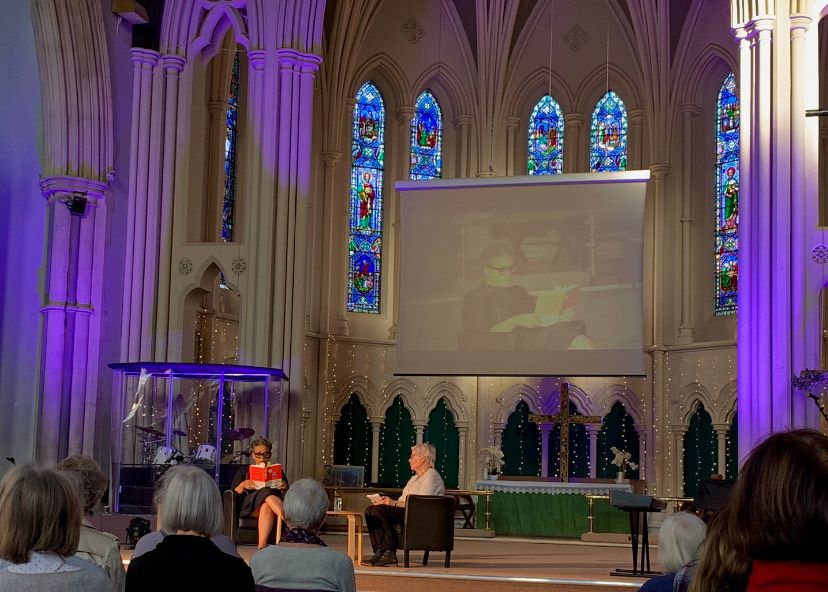

Kit de Waal – Without Warning and Only Sometimes

Novelist, editor, and memoirist with her second book longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the event Epigram attended on LitFest’s Sunday programme was Kit de Waal’s Without Warning and Only Sometimes. In conversation with Sarah LeFanu, Kit de Waal produced a comedic yet heartfelt discussion about her latest book.

Serialised on BBC Radio 4, Without Warning and Only Sometimes is a compelling memoir about discovering what it means to be loved in a family defined, yet conflicted, by religion and culture, and answering the question of “what was it like to be strange?”.

The title of the memoir derives from a warm memory; Kit recounts her time in a freezing bedsit, where her room sat on top of the basement which held an industrial boiler. The Landlord would move the boiler “without warning and only sometimes”, wafting a comforting draft through Kit’s floor vent. Kit explained that goodness and warmth happens in life… without warning, and only sometimes!

Born in 1960 and growing up in Birmingham as a “mixed race” woman, Kit already felt out of place. Attending a Grammar School circa 1972, Kit explained that there were three Black children in the entire school. Kit went on to describe her extended family dynamics that contributed to her feelings of being “unusual”. She spoke of her two grandmothers who withheld love but humorously stated they were the “same woman in different colours”. Kit explained that both of her grandparents migrated to England for a better life, and the idea of their children marrying a different race horrified them.

Being a product of this united love, Kit and her four siblings were othered within their own family. Kit however found comfort and a “tribe” with her siblings. Once her memoir was complete, Kit sent proofs to her siblings and gave them the power of veto – anything they wanted out, she would delete. Only one sister objected to two words. It was important to Kit for their blessing, acknowledging that she had different experiences, but their blessing meant she had accounted for their experience too. Kit held sentiment in saying “I wouldn’t be here today without them”.

Honest, witty, warm-@KitdeWaal on her novel Without Warning and Only Sometimes with Sarah LeFanu @CliftonLiterary @BristolLibrary pic.twitter.com/OVzYqV7Dd9

— Jane Shemilt (@Janeshemilt) November 14, 2022

Kit’s childhood was defined by her mother’s Jehovah’s Witness’ baptism, where celebrations were taboo and her weekends were spent preaching on doors. Kit performed a reading from her memoir, speaking of Jehovah’s Witness’ constrictive teachings and how this conflicted with her personal desires – “having freedom and fun is worth the end”. Kit ultimately left home at sixteen, no longer wanting to live a “joyless” Jehovah’s Witness lifestyle.

Kit spoke fondly of her parents, with reminiscence and a deeper longing for what she was deprived of. She spoke of her father’s disappointment of not belonging in England, nor the West Indies, but also of his passion for classic film that sparked her interest in storytelling. Kit described her father as “haphazard” and “unpredictable”, and seemingly uninterested in his children until he cross-examined them on film trivia. Kit had more of a complex relationship with her mother, an assumed bipolar, which Kit described to have shaped herself into an observer, a skill vital for writing.

Dedicating Without Warning and Only Sometimes to her parents, Kit made a disclaimer that “they were not good parents”, but she was loved, and that was all that mattered. Kit found warmth and comfort with her parents without warning but only sometimes, but for this she was grateful for the occasional instead of nothing at all.

I left the event feeling warm at the tenderness in which Kit conversed, but also broken at the nostalgic longing that was portrayed through Kit’s comedic and light tone. It was a beautiful conversation and reading, and I urge everyone to read Kit’s extraordinary memoir.

Featured Image: Clifton Library, courtesy of Epigram

Will you be attending Clifton Village LitFest next year?