By Mia Stevens, MA English

THE CROFT / Flamingos, feathers, flamboyance - we recognise the feeling of camp, but how do we define it? Mia uses Sontag's essay to distill the true identity of camp.

When one thinks of “Camp” one can’t help but conjure a number of exciting and seductive possibilities. Eurovision, for example, the return of ABBA, or the hyper-realistic paintings on the sides of funfair rides. Bubble tea, High School Musical, Katy Perry’s music videos, The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Namely those which seek to revel in a sense of flamboyance, exaggeration, artifice, and most importantly, a complete and un-wavering seriousness in the art they set out to create.

Next year will see the sixtieth anniversary of Susan Sontag’s landmark essay ‘Notes on Camp’. Since its original publication in 1964, Sontag’s paradigm for camp has been called upon over the years in an effort to define such an elusive sensibility. It was used as the theme for the 2019 MET Gala, for Drag contests, Instagram captions, academic essays. Each iteration of Sontag’s ideas welcomes new candidates into the canon of camp.

As Sontag points out, it is not easy to define a sensibility, nor is it easy to categorize what is or isn’t camp, or even for whom camp is reserved or to be utilized. Camp has in recent years become synonymous with certain people, mannerisms, even modes of speech, namely those of the gay community. In fact, “camp” is often employed as a surrogate definition for the word “gay”, though more so to describe gay men than women. Speaking from inside this community, I often find myself pondering questions to do with the extent to which campness is indeed a conscious or subconscious mode of gay style. To what extent, if any, is it intrinsic to queerness?

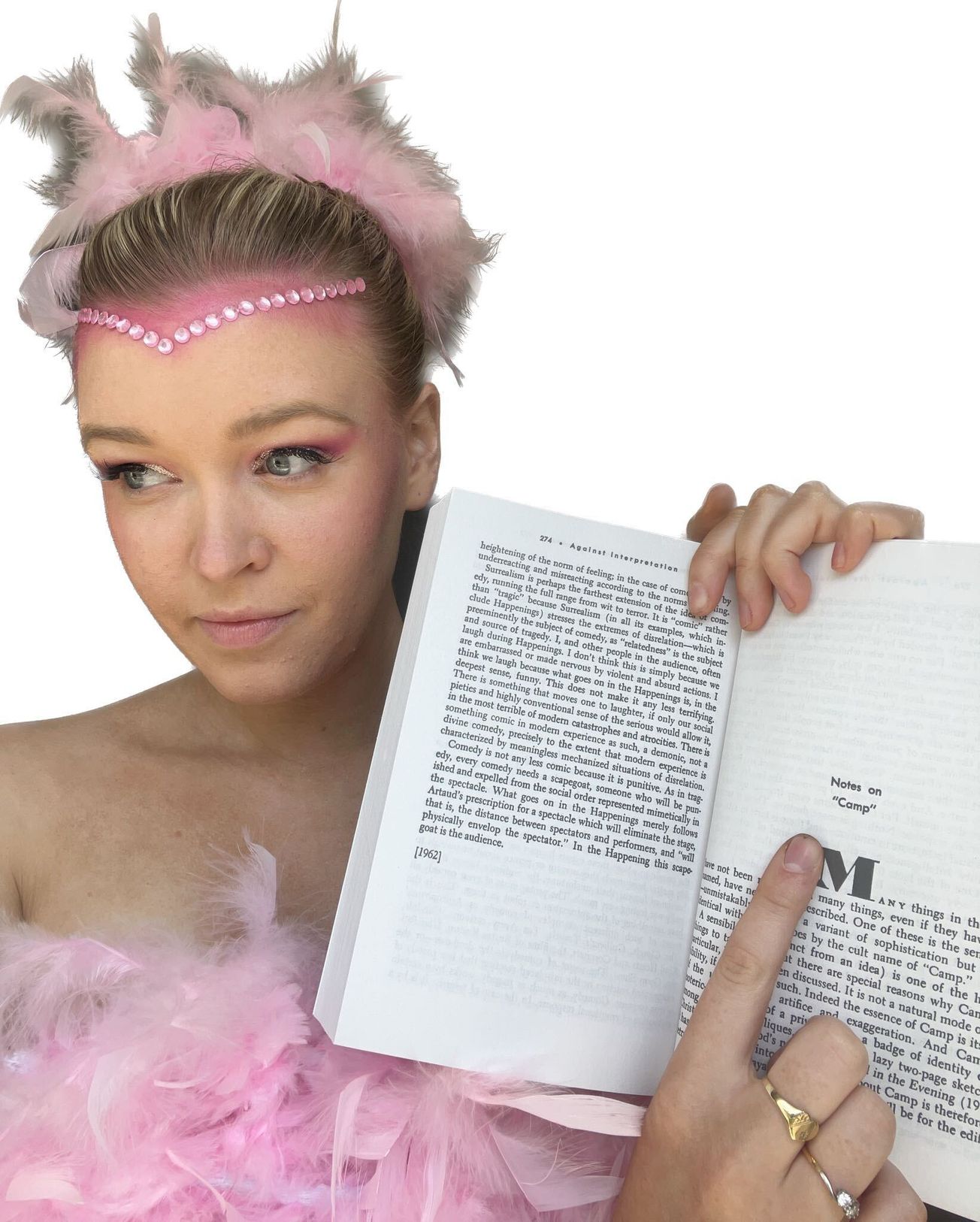

Now, if you will indulge me for a moment, I shall turn to myself as an example. I am fully aware of the vulgarity of this move, but I feel it is the best way I can describe the point I am trying to make. I recently attended a costume party in which the theme was Alice in Wonderland. Naturally, I decided to go as a flamingo, and so fashioned a bright pink two-piece made entirely of feather boas. This was accompanied by a rhinestone “beak”, false eyelashes and a matching feather headpiece.

It was, by my peer’s definition, undeniably camp. By Sontag’s though, not so much. My idea behind the costume was completely academic – and I mean that in the fullest sense of the word. I had decided before the event that I was to be the campiest person in the room, and so I consulted Sontag’s essay for a comprehensive, fully researched and cited definition. I enlisted this quote as my inspiration:

‘The Hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.’

This is, of course, where it all went wrong. Not only was my costume just short of three million feathers, but my desire to be camp was entirely intentional. Sontag declares that ‘pure camp is always naïve.’ Camp which knows itself to be Camp ‘is usually less satisfying.’ I had, on my own merit, offered up a ‘less satisfying’ version of camp. If camp does indeed ‘rest on innocence’, then I was guilty of betraying the very mode in which I sought to create.

However, not all is lost. As is common in the self-reflexive nature of Sontag’s essays, her opinions fluctuate within paragraphs of each other. Whilst on the one hand she does peg campness to naivety, she also holds space for dead ‘seriousness’, a mode of camp that is ‘wholly conscious’. Perhaps then, I am to be forgiven. Either way, if one chooses to deconstruct every costume for every party in the way I do, then one is likely to leave feeling rather deflated. Whether or not my costume was a true example of camp is not the point. What is, however, is the way in which I think about my expression of camp.

Here's an obvious question, and one which troubles me – is my campness influenced by my queerness? Is my affinity with all things extravagant linked to my lesbianism? Do my peers see my life-sized cutout of Dolly Parton and my Cher fridge magnet as an inevitable by-product of my homosexuality? Quite possibly. But not entirely.

Of course, camp has historically been associated with queerness; Sontag dedicates a small proportion of her essay to unpacking the ‘peculiar relationship between Camp taste and homosexuality’. Whilst the essay itself does not specifically mention Sontag’s own queerness, does she really need to come out? I think not.

Camp can be a way to express one’s queerness, it can signify one’s affinity with the gay community. It can be a form of protest, propaganda, a political statement, even. (It’s no accident that the Gay Liberation Front adopted a rainbow flag as its recognizable symbol). However, not all queer people are necessarily drawn to camp, and not all “camp” is necessarily the “property” of queer people. The love of all things unnatural, a taste for everything that is extravagant, theatrical, or “too much” cannot be confined to one singular identity group.

I believe camp comes down to style. It’s a way of looking at the world and seeing the potential for extravagance. To “be” camp is to find joy in a mode of excess, to exaggerate, whether in naivety or full seriousness. It is to see the aesthetic value in one’s clothes, one’s mannerisms, in music, art, literature, in a building or in a lampshade. In Sontag’s words, ‘camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature’. With this in mind, I think it is fair to say that Camp is, and can be, for everyone.

| Featured Image: Mia Stevens |

| Copy Editor: Grace O'Sullivan || Quotations Taken From Sontag's Essay, Sontag, S. (2018). Notes on Camp. Penguin Classics.|

What does camp mean to you?