To celebrate International Women's Day 2020, Epigram's Features Team look at some of the women at the University who have inspired them as both academics and public figures.

Lady Hale

By Georgiana Scott, Investigations Correspondent

The barrier-breaking, success defining career of Baroness Hale of Richmond, most commonly known as Lady Hale, is unrivalled in its impact and legacy.

State-school educated, she was one of only six women to 100 men studying law at the University of Cambridge and became the first woman appointed to the Judicial Committee.

Recently retiring from her position as President of the Supreme Court, in a male-dominated industry she has defied odds and challenged the status quo, shattering glass ceilings not only for herself but for other women entering the legal field.

She recently became a media sensation when she historically ruled that Boris Johnson’s proroguing of parliament was unlawful, to the extent that even her infamous spider brooch has a Twitter account. But in the legal world her sensational reputation has always preceded her.

From writing influential books such as 'Women and the Law’ and being at the forefront of many landmark reforms such as the 'Children Act of 1989’, she has completed groundbreaking work in human rights law.

Aged 75, she is not done. She is now sitting in the Hong Kong Court of final appeal and plans to even make her way into the House of Lords. University of Bristol Chancellor for thirteen years, she frequently returns to the city and meeting her upon her last visit to Bristol, was nothing short of fascinating.

Her no-nonsense attitude and intellectual fierceness were certainly intimidating, but combined with her spirited persona, she commands nothing but admiration and respect.

On International Women’s day, I shall leave you with her motto ‘Omnia Feminae Aequissimae’ meaning ‘Women are equal to everything.’

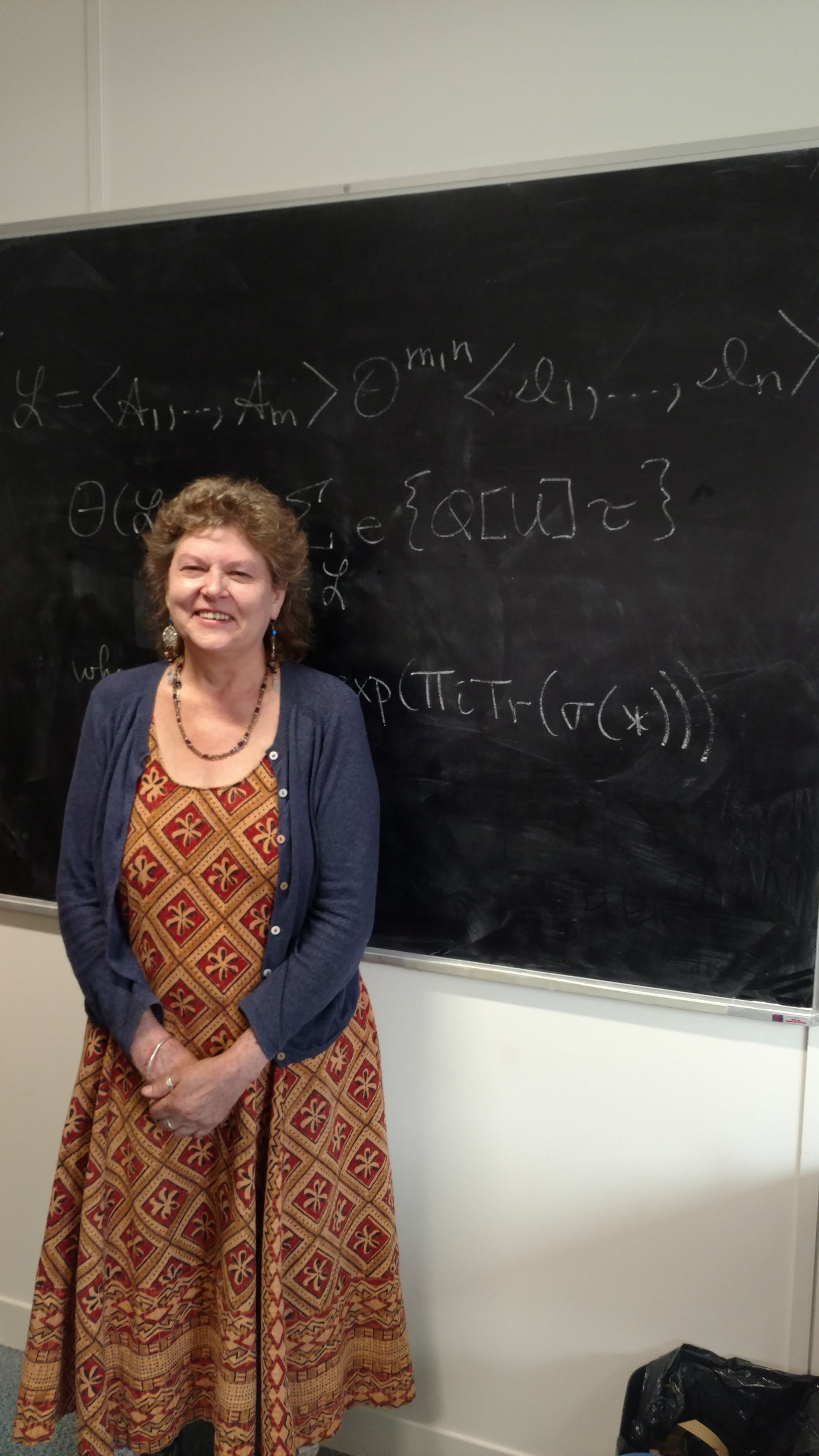

Dr Lynne Walling

By Oliver Cohen, Features Digital Editor

As if heading up Bristol's pure mathematics institute wasn't achievement enough for Dr Lynne Walling, she has combined her contributions both to academic research with significant outreach work boosting and talking about diversity in Mathematics with a focus on female participation.

Gaining her PhD from Dartmouth and having worked at the University of Colorado as well as the National Science Foundation in the US she joined the Bristol Mathematics department in 2007 where she would take up her directors' position 4 years later. In her own words, she works on "Siegel modular forms using algebraic techniques, Hecke operators, and the theory of quadratic forms." Such research has gained her fellowship from the American Mathematical Society as well as research grants from among others the NSA and NSF.

While her research topics may be hard to understand for a non-mathematician, her impact on boosting diversity within maths certainly isn't. Having given interviews in newspapers as well as contributing to panel discussions and conferences on the subject of diversity, she is working to rectify the current issues of gender hegemony in a typical Mathematical student cohort.

Figures from 2013 illustrate the issue bluntly: Despite making up over 40% of bachelors in Maths, women are only 19% of doctorates and 6% of professors. With the likes of Lynne working in the field, hopefully, such figures will soon be relegated to the past.

Dorothy Hodgkin

By Ellie Brown, News Subeditor

She is most often remembered for her outstanding contribution to the field of Chemistry, but Dorothy Hodgkin, who became the University’s first female Chancellor in 1970, was as much of a pioneer outside academia as within it.

Born in Sudan in 1910, Dorothy travelled throughout her life and worked with international humanitarian movements, such as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, of which she became president in 1976. She was involved in anti-Vietnam war movements, becoming chair of the Medical Aid Foundation for Vietnam in 1970, and supported dissident scientists in the Soviet Union through writing personal letters to her contacts there. She won several Peace Prizes for her work, including the Lenin Peace Prize in 1987.

The biographies available on her suggest that Dorothy faced fewer barriers to a career in academia than would have been expected for a woman in the 1920s. Her father encouraged her involvement in science and application to Oxford, while as she advanced in her academic career her sister Joan moved in to her house to help look after her children. But her achievements were still ground-breaking; for example, she was only the third woman to receive a first-class degree from Oxford.

Her determination was tested by a later development, when, at the age of 28, her hands became swollen and disfigured due to chronic arthritis. Yet ‘regardless of her frail and later crippled body’, as a speaker at her funeral put it, she made incredible discoveries in her career, chief of which was the structure of complex molecules such as insulin and penicillin, which won her the Nobel Prize in 1964.

As Chancellor at the Bristol she was noted for her dedication to the role. She campaigned for the University’s department of Architecture to remain open following Government cuts in 1982, and she took time to get to know the students, visiting the Student’s Union the day of her installation as Chancellor. And a former student of hers recalled the ‘warmth and kindness’ of her laboratories.

Despite her impressive achievements, it seems that Dorothy remained remarkably down-to-earth. To me, her lifelong concern for others is just as inspirational as her commitment to her subject, and is something which everyone can learn from.

Professor Olivette Otele

By Robin Connolly, Features Editor

Having joined the university in January of this year, Olivette Otele is certainly a force to be reckoned with. Having received her PhD from the renowned Universite La Sorbonne in France, Otele became the first Black woman to be appointed with a Professorship in History in the UK in 2018.

She specialises in transnational histories, collective memory and geopolitics. She has written books such as African Europeans: an untold history (2020), Post-conflict memorialization: missing memorials, absent bodies (2020) and her doctoral thesis Histoire de l'esclavage britannique : des origines de la traite transatlantique aux premisses de la colonisation (2008). She joined Bristol this year, having been appointed the new title ‘Professor of the History of Slavery.’

As well as working in the academic field and publishing her own work, Otele is the Vice-President of the Royal Historical Society, a society which promotes historical research and supports historians working for the public.

In an interview for Epigram last year, Otele stated that ‘by appointing me it means that university is ready, to deal with that past and really to be open about whatever I'm going to find.’ She went on to say that it will ‘be fantastic to have that history of Bristol taught at Bristol with new elements, new archival material and integrate the past and the present with the memorialization of the past.’

Hoping to inspire young Black women into academia and to act as a role model for the next generation of Historians, Olivette Otele is definitely one to look out for this International Women’s Day. I look forward to seeing what she achieves next.

Featured image: Flickr / David Foltz

Do you have any tutors or lecturers who have inspired you? Let us know!