By Noah Robinson, First Year Law

Like the Harappan myth, where the creator blows breath into a clay figure to bring them to life, Bharti Kher injects a liveness into traditional elements of Indian culture in a new exhibition, ‘The Body is a Place’, currently at the Arnolfini.

Beginning downstairs, the adeptly named Links in a chain naturally embody its kinetic sense of energy. Sitting in large freestanding black metal frames, Kher combines pages of educational children’s books from the 1930s with an eighteenth-century medical book of drawings of the brain.

Leaning into the Surrealist tradition of assemblage, the work pulls on the suggested links between the found pages only to inevitably disrupt them. They range thematically from the absurd to the psychological, where they stand at their best.

It is a critique of cultural norms, overwriting the dominant narrative of whiteness which Kher experienced when growing up in suburban England. There is nothing static here, with a real immediacy in the modifications to the pages of text.

The work lining the walls of the lower gallery feels mostly anatomical in nature, building on familiar yet strangely distant shapes.

Her Body Incantatory drawings have a playful energy to them, freely chaotic and unpredictable. As part of Kher’s practise, they are intuitively made as part of her own “hand-brain-body-art-language”, an entirely self-created term.

The drawings feel like an expression of the unconscious, part Freudian, with wild reoccurring circular and structurally cellular shapes. At times, they can lose their form, too abstract to have meaning, but are undeniably aesthetically arresting.

Entering the upper gallery, the space is visually dominated by a wooden loop, part suspended above rough pieces in a contorted and united balancing art. This impossible feat is naturally daring.

Recalling Camus’ reinterpretation of the Greek myth, Consummate joy and a Sisyphean task imagines the crude act of pushing a boulder up a hill as a meditative undertaking.

It stands in contrast to the warm tones of the other work, made of pieces of wood at different levels of processing. It naturally comments on the physical act of manual labour and the work of the body. Whilst it is conceptually weighty, it leaves much to be desired. Its array of objects pushes us towards themes of place and belonging, but Kher’s symbolic use of geometric shapes is entirely lost.

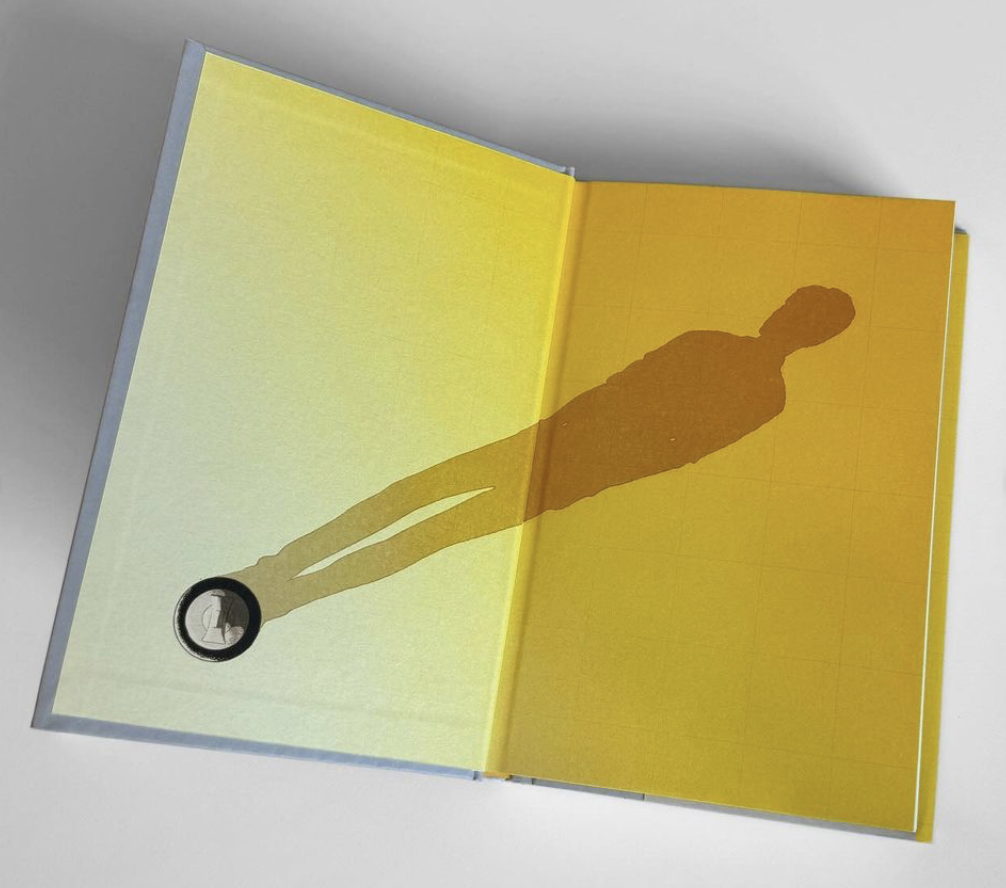

The circle frames the Heroides series, where Kher uses bindis as a language to create fictional love letters inspired by Ovid. After moving to New Delhi in 1993, Kher began to work with bindis, a now vital part of her practise. As she describes “they carry memory and narrative sleights of hand…a leftover of some experience”, looking back to their traditional religious significance.

Rather than cellular shapes, in this series, the bindis take on the form of constellations, with each circle recording an individual story or moment. There is a sense of possibility in the work’s expanse, connecting past and present and placing it into a new and exciting context.

This process of transformation is common to Kher’s work. Moving into a side room off the upper gallery sit a collection of what look like geological masses. The Chimera sculptures began as a plaster cast of a head and face, later enveloped in layers of wax and hessian fibre.

Sitting on mismatched plinths, they appear to be preserved relics of an ancient tradition. They are barren of any of their original, distinct human features, recording imprints and impressions. Compared to her boldness in Six Women, casts of six sex workers, and earlier sculptures, Chimera feels distinctly passive in its interrogation of the body.

Kher transports us from considering the past to looking forward to the future.

Virus is a site-specific work which Kher began in 2010 predicting such developments as well as recording events in her personal life.

There is an arresting contrast in the bold golden typography and the craftmanship of the wooden box: something slightly ethereal. The bindis, as the contents of the box, take on their traditional association as marking the seat of concealed wisdom and a gateway to spiritual insight, although Kher’s predictions are far from idealistic, depicting an Eliot-esque wasteland of socio-economic inequality and unmitigated climate change.

Kher deceptively celebrates the aesthetic, the beautiful in ‘The Body is a Place’, but at its core the exhibition is a complex examination of history, tradition and culture.

Kher’s exhibition runs from 22nd October - 29th January at Arnolfini.

Featured Image: Courtesy of Noah Robinson

What is your favourite piece at Bharti Kher's ‘The Body is a Place’?