By Anna Page, Fourth Year English and French

It remains an enduring duty of the art world to bring to light the talent of Black artists after centuries of absent recognition. Like many pillars of our society, the arts have had to undergo a significant amount of reform after being revealed as systems propagating systemic racism. Historically, it has been difficult for people of colour to see themselves represented in an art world dominated by an Occidental tradition that for so long actively sought to oppress them.

Yet, today as we observe the 52nd Black History Month, this narrative is appearing to change. Black artistry is finally receiving the acknowledgement it deserves. This month, we focus on the role of the arts in recognising the violations of the past and presenting an optimistic manifesto of racial equality for the future.

An example of such an evolution in the art world comes in the form of the diversity of the exhibitors of the latest Biennale occurring in Venice this year. The Biennale, a large-scale international art show established in 1895, has historically been one of the whitest institutions in the art world. In previous editions, we have witnessed an average of nine out of the ten exhibitors being white men.

This year, however, for the first time in history, the two Golden Lions, the Venice Biennale's highest honours, were awarded to women of colour: Sonia Boyce and Simone Leigh. Yet there is still work to be done. In 2019, a study conducted on the diversity of artists in major U.S. museums, found that 85% of the artists exhibited in the 18 largest US museums were white.1 African American artists were the least represented demographic group at 1.2%, despite constituting a quarter of the US population.

When discussing the art produced by Black artists, it would prove ultimately reductive to refer to them as a community void of differentiation. Although there are many commonalities in the work produced by the Black community, many Black artists have spoken out against the racial gauze that society has sought to wrap around their work.

Nevertheless, for the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of colour) artists who do intend to abord the subject of race through their artwork, many common themes seem to be at play. These include discussions of power, the impact of Empire, Black experience in the African diaspora, as well as the highlighting Black joy and solidarity.

Alongside his peers of Kara Walker, Jean Michel Basquiat and Jacob Lawrence, Kerry James Marshall propagates a dialogue attempting to open the doors of white spaces previously excluded to Black artists. Resisting the temptation to bend to Western influences in their quest for acceptance, we have witnessed a movement of emerging Black artists redefining the contemporary art scene over the past century.

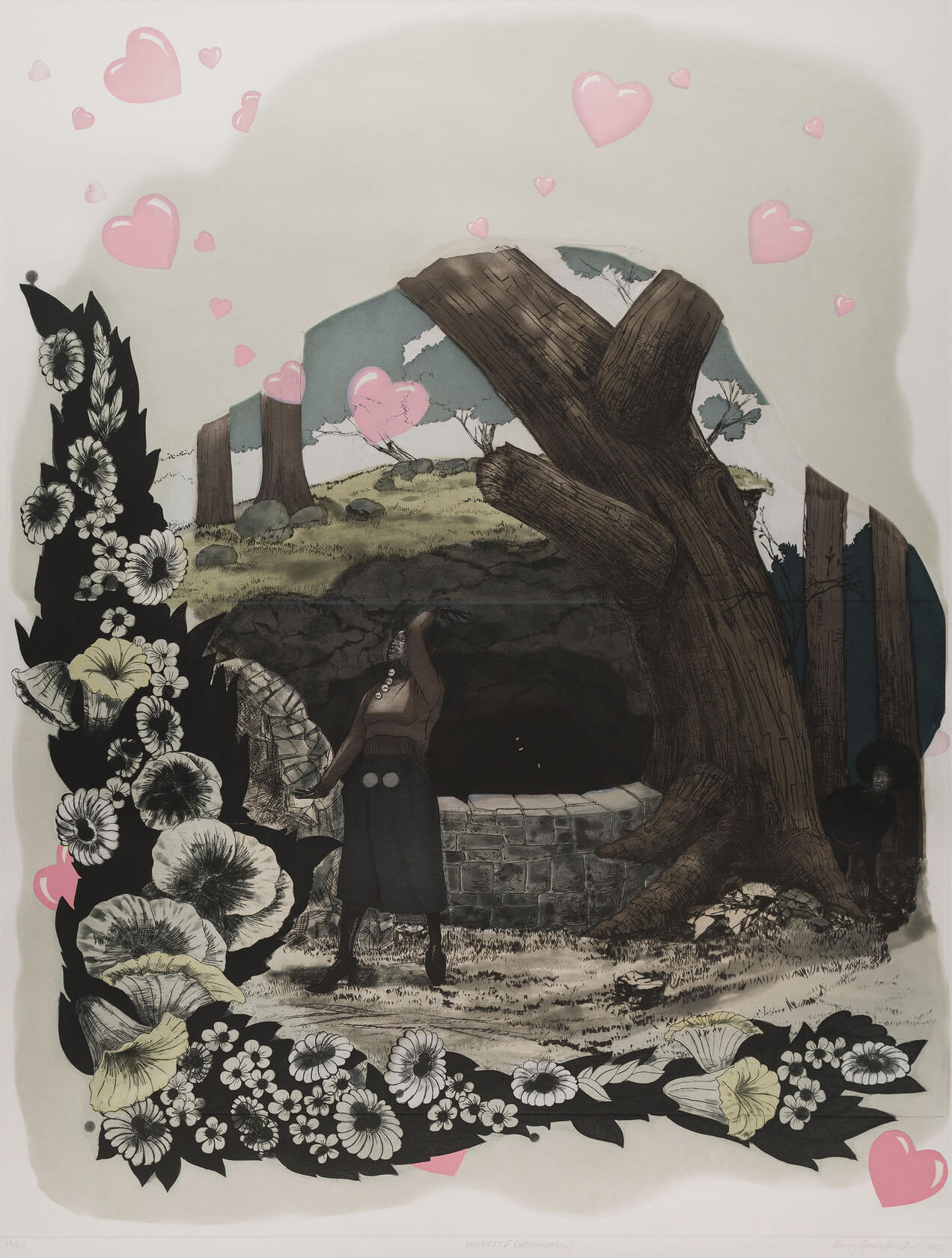

Racially engaged artworks are resolutely committed to voicing Black narratives, and one such artist who does just this, is Kerry James Marshall. An African American artist, born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama, his works touch upon the issue of the under-representation of Black people in art history. In his series Vignette, Kerry James Marshall stages Black couples in scenes familiar to a Western audience. The result is striking and encourages reflection on the place of Black people in art history and in museums.

In Wishing Well, Kerry James Marshall sets out to dismantle the cornerstones of the European art tradition that have been built upon the marginalization of artists like himself. He does this through the employment of a Rococo pastiche.

Intent on the imitation of the works of European masters of the 18th century tradition, Marshall challenges the artistic establishment. Rococo art is often associated with staged scenes of young lovers seducing each other in romantic milieus. By altering the skin colour of these figures to represent people of colour within his Rococo art piece, he shows that he too can create art in a style deemed “civilized” to the elitist eye. Whether the imitation infers homage or parody is for you to decide.

What does appear clear is Marshall’s ingenious way of carving out a space for Black artists like himself in the 21st century. As viewers, we are invited to observe this artistic tradition reimagined through the Black artist’s gaze and take note of any racial biases leftover by colonialism within the artistic canon. In time, Marshall hopes that his inclusion of Black figures within artworks presented in museums will become normality.

In the years succeeding the BLM movement, which have been peppered with instances of racially motivated violence reported in periodic occurrence, it is tempting for us to discount the ‘utility’ of art in this struggle for racial equality. But art, especially for marginalised communities, is necessary. It will be interesting to see where artists such as the prize winners of this year’s Venice Biennale, Sonia Boyce and Simone Leigh, take this discourse in the future.

Featured image: Kerry James Marshall, Vignette (The Kiss) (detail), 2018 - Courtesy of Art Basel

What is your favourite piece in Kerry James Marshall's Vignette collection?