By Claire Meakins, Film & TV Critic and Subeditor

American Psycho (2000), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), and Nightcrawler (2014), to name just three of many, are films that have re-emerged with full force into the cultural mainstream. As well as all of them attaining both critical and commercial success, they have become some of the poster boys of a recent trend: the ‘literally me’ film.

Characterised by lone male protagonists; acts of violence and/or hedonism; a theme of dissatisfaction with the world; and commentary on materialism and masculinity, ‘literally me’ films have been embraced both by meme makers and genuine adherents of ‘sigma male’ culture. Attracting predominantly male admirers who find them relatable or appealing, their characters have become iconic and, in some cases, even inspirational.

American Psycho is perhaps the film most famously associated with the phenomenon, yet it raises some troubling questions. Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) is a sadistic murderer and, despite his bravado, deeply insecure; he is hardly an ideal role model. Despite this, film clips depicting Bateman in a sharp suit abound on sigma male motivation pages. While many of these pages do just offer mostly harmless and cringey self-help advice, it’s still disturbing that a violent psychopath is so prevalent on them.

Here, I think it’s important to clarify what a sigma male is. The term was first coined by a far-right activist in 2010 but has only risen to prominence fairly recently. In line with the idea of ‘alpha males’, the sigma male is the next step up on the ladder, being the supposed pinnacle of success. Often associated with the misogynistic online community ‘MGTOW’ (Men Going Their Own Way), the sigma male is muscular, wealthy, disciplined, and individualistic.

Patrick Bateman does outwardly fit into this mould, but it is the tension between the external and internal that is, in fact, the driving force of the film. Bateman is a victim of the consumerist and corporate culture these pages often promote, with his goal being ‘to fit in’ with the very people he despises.

He lives behind a mask of expensive beauty products, glamorous women, and cold charisma, terrified of losing the status he has achieved through conformity. This pressure forces him to restrain parts of himself until, eventually, they cannot help but violently explode.

Rather than being an emblematic sigma male, Bateman is a satirical depiction of what happens when men try to be one. The standards that accompany his lifestyle are just as psychopathic as he is. Stamping the sigma male label on Bateman is almost cruel; even outside of the film, he is trapped in his all-consuming lifestyle.

Nightcrawler plays with similar tensions, with Lou Bloom (Jake Gyllenhaal) being so obsessed with success that he willingly engages in crime and remorselessly manipulates everyone (even the dead) to get ahead. Indeed, he does somewhat ‘succeed’ by the end of the film, leading to some viewers admiring his questionable but dedicated work ethic.

Yet, as with American Psycho, it can’t be said that Nightcrawler necessarily wants us to side with Bloom; he may ‘succeed’ but he’s cruel and unhinged. Undermining the sigma males’ admiration, in deliberately comic moments, he delivers lines that sound as though they’ve been plucked from self-help books to try to justify his horrific behaviour, they’re definitely not pieces of genuine advice.

For instance, the film ends with Bloom reassuring his interns by saying: "I will never ask you to do anything that I wouldn't do myself". This is usually no more than a piece of jargon overused by employers to make it seem as though their company is one big happy family. However, given Bloom’s previous actions, the line gains a chilling resonance as we realise that his cycle of violence will continue.

It is the tactical removal of context that seems key to the allure of these characters. When you ignore that Bateman and Bloom are damaged and damaging men, they are, in many ways, admirable. It’s easy to miss the joke (accidentally or otherwise) and see Bloom as a man who will do whatever it takes to succeed, and who comes out with lines that you can post on your motivational Instagram.

While liking evil characters or taking them out of their original context isn’t necessarily problematic in and of itself, ignoring or even romanticising their despicable nature to make them into heroes certainly is.

The Wolf of Wall Street is a complex example of this issue, balancing on a fine line between obvious satire and problematic indulgence. Leonardo DiCaprio stars as, real-life entrepreneur and financial criminal, Jordan Belfort and, although Belfort is immoral and intensely materialistic, DiCaprio plays him with charm that gives him an undeniable appeal. The film is a masterful character study, but this is often overlooked in favour of admiring Belfort’s extravagant lifestyle.

The real-life Belfort, released from prison in 2006, is now a motivational speaker and author of books aimed at providing the secrets to getting rich quick and, as such, he himself has a fanbase that primarily consists of sigma males and the like.

The film only added to Belfort’s fame, leading even more people to see the acquisition of obscene wealth, with little regard for ethics, as the epitome of success. While Martin Scorsese may not have intended for it to have this effect, it’s clear that the film’s ambiguous moral compass has given it a dangerous legacy.

The film isn’t just controversial in terms of the representation of Belfort, both heavy drug use and the objectification of women are casually depicted throughout. The character of Naomi (Margot Robbie) exemplifies the latter, with Robbie’s good looks being Naomi’s only notable characteristic.

Although the film does invite us to sympathise with her, she spends most of her screen time being sexualised and objectified both by other characters and the camera. Belfort views her as a trophy to be won, and once he has ‘possession’ of her, he cares little about her feelings; women, to Belfort, exist for their looks.

In all three of the films I’ve mentioned, the protagonists use and abuse the women around them, often through forms of sexual harassment. Being able to attract the most beautiful woman in the room may be desirable, but it might be worth examining how much of these characters’ desire is based on objectification, a desire to possess, or viewing women as mere status symbols. By glorifying these ‘literally me’ films and characters, even their worst traits can be romanticised.

While these films are often great watches, it’s important to remember that they are generally satirical. Overlooking the fact that their protagonists are often irredeemably despicable can create dangerous assumptions about the nature of success, masculinity, and individualism. No matter what the internet says, chopping up Jared Leto with an axe probably isn’t the solution to your problems.

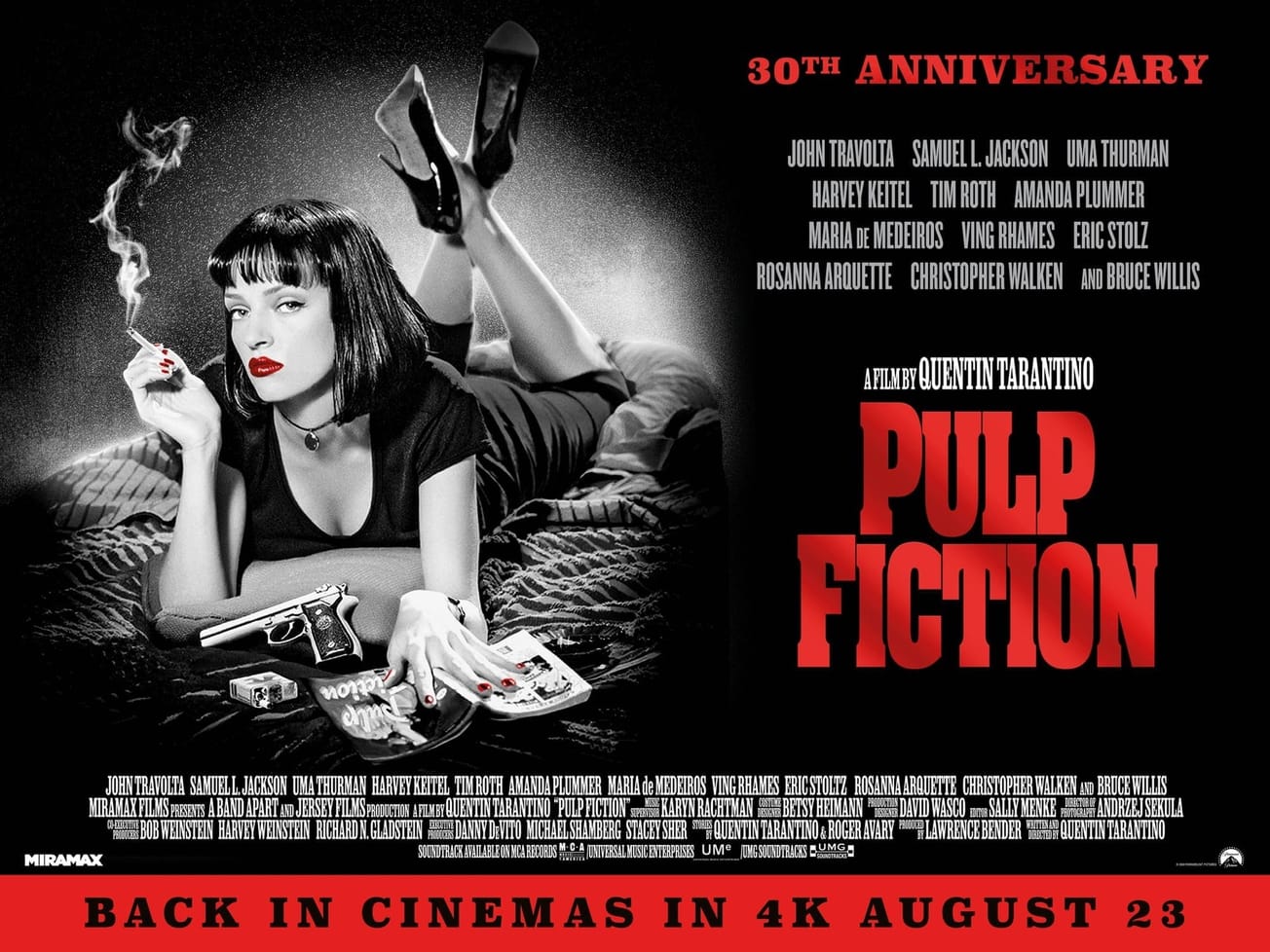

Featured Image: Courtesy of Mary Cybulski, Paramount Pictures on IMDB

Do you agree with Claire's critique on 'sigma males'?