By Aidan Szabo-Hall, Features Investigations Editor

We are living through a sobering reality—that surreally possesses both a record number of billionaires and foodbanks—far detached from the optimistic vision of a new ‘golden age’ that was promised for this country a little over three years ago. Once-distant fears about the financial impact of the pandemic on our future livelihoods have become finally tangible.

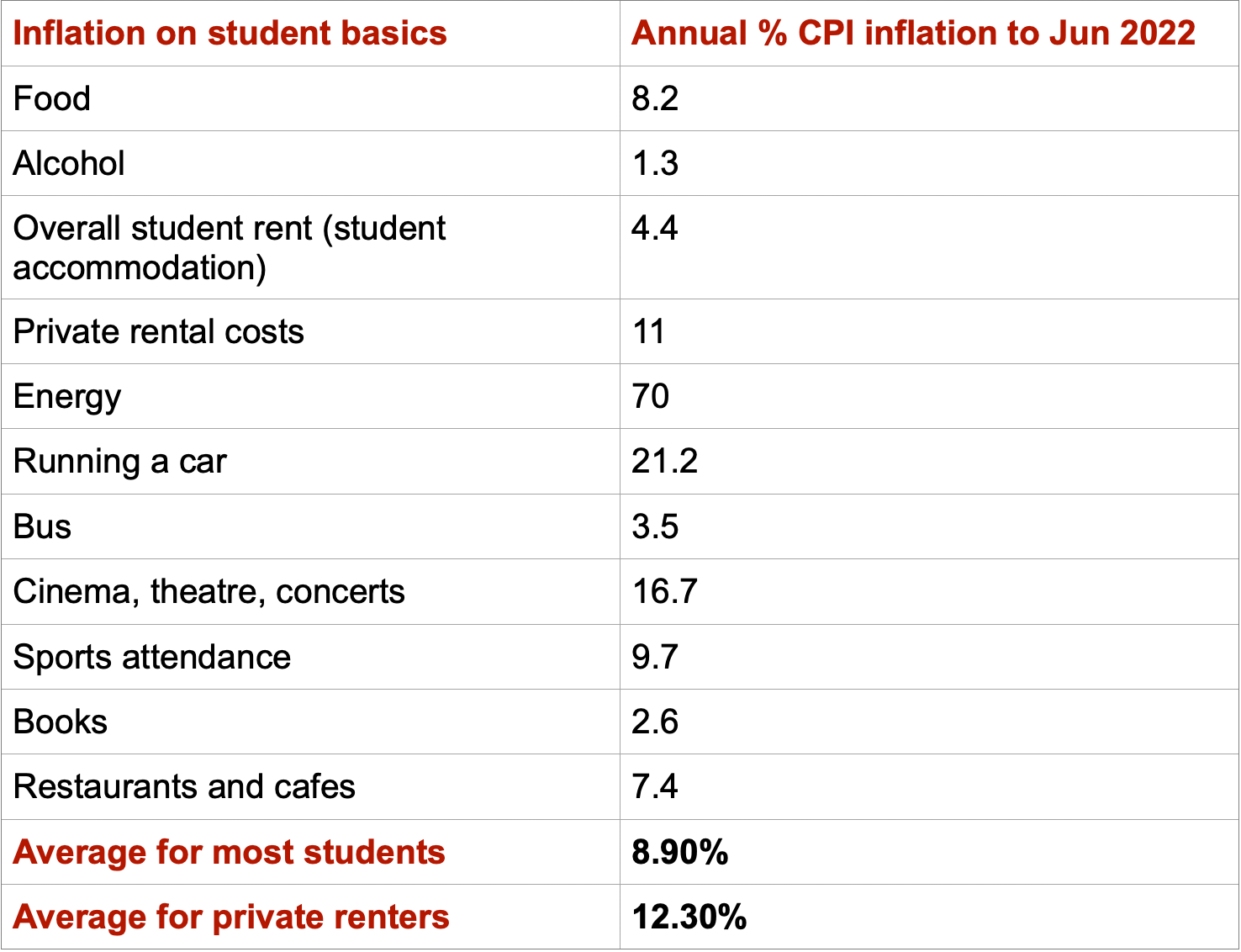

Soaring prices, stagnant wages, increasing demand for food banks, ever-rising energy price ‘caps’ and inflationary levels predicted to rise above their current forty-year-high of ten per cent. As gas and oil giants reap unprecedented excess profits, millions will have to be frugal about every last penny and alert to every socket, light switch or heater left unattended.

This economic catastrophe also places students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in a vulnerable position.

It threatens to thrust upon them agonising decisions such as choosing between socialising or eating. The inequality between low-income students and their more affluent peers will become more starkly visible. For some, preexisting notions of self-consciousness and anxiety surrounding their social class will become more pronounced.

Tiegan Bingham-Roberts is a Bristol alumnus, former member of the 93% club—an organisation established to promote opportunity amongst state-school students—and is now a board member at upReach, another social mobility organisation. She is fearful about the impending impact of the cost-of-living crisis, and how it threatens to intensify the disparity between affluent and less financially secure students at Bristol. Speaking to Epigram, Tiegan stressed the obvious differences between students on campus from privileged and less privileged backgrounds: ‘Perhaps it's in the way they dress because of the clothing they can afford; perhaps it's in the supermarkets they shop at because of the food they can afford; perhaps it's the social activities they can participate in because of their spare income’.

She elaborated ‘It is these everyday considerations that will heighten class and income differences, especially because statistically in a university household there will be students from diverse backgrounds with diverse incomes at their disposal. This coming winter, there may be more friction between housemates as some will be more aware of the cost-of-living crisis than others’.

Touching on the ways in which the wealth disparity between students may manifest, Tiegan added ‘Students who receive money from their family towards rent or bills or living likely feel less of a direct responsibility to turn off the lights in their accommodation, be frugal about turning on the heating, and conscious about how much gas they're using to cook their dinner. It is students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds who will likely feel more of a responsibility for these things’.

‘Students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds should not have to forfeit the social opportunities that university provides because they can't afford them’

These imbalances and divisions are likely to become most strikingly apparent in universities where students from poorer socioeconomic backgrounds account for a marginal proportion of the intake. Bristol is one such example; with a disproportionately high number of private school students—which currently stands at 24.5 per cent—and a state school cohort that historically falls far short of the national average. Its purported reputation as ‘elitist’ has likely been exacerbated as a result.

Universities reacting faster to the Queen dying than supporting their students during a cost of living crisis is quite something.

— Rosie 🇪🇺 (she/her) (@Rosie_Baillie_) September 13, 2022

Yes, writing a statement about the Queen wouldn't take long, but neither would a statement acknowleding our concerns.

As someone once entitled to free school meals and who grew up using foodbanks, Ms. Bingham-Roberts is fearful about the potentially diminishing effect of the crisis upon the University experience of poorer individuals: ‘Students with less income will perhaps go hungry or cold some days, or spend that extra ten pounds on a trip to the pub with their coursemates to keep up appearances and ensure they have the full university experience they had worked so hard towards’.

Tiegan voiced this as her greatest worry, because she has firsthand experience of it: ‘Students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds should not have to forfeit the social opportunities that university provides because they can't afford them, likewise, they should not have to forfeit meeting their own basic needs as if this is a normal trade-off’.

The looming crisis will make access to events, activities and resources increasingly unattainable for some. But it also threatens to incur profound social implications. For low-income students, the challenge of social assimilation could be made even harder. Where less affluent individuals may have previously internalised their class status in an effort to ‘fit in’, doing so becomes ever more difficult when you cannot afford to do the same things as your more privileged peers.

Tiegan touched on this: ‘The increased cost of resources and travel means that many of the things that might first appeal to prospective or current students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds are no longer viable. They can't easily travel into London for an internship they've been offered a place on; they can't easily buy the books they need to study for their course; they can't buy a membership to the societies that first excited them at Freshers’ Fair; and they can't participate in all the social activities and make the friends they've been looking forward to make’.

Amid the student cost-of-living crisis, students can’t be left to make up the shortfall when it comes to financing their tech needs – they need help from universities and government, say @BristolUni’s Sarah Purdy and Steve Hall #THECampus https://t.co/y0tn5VcyBy pic.twitter.com/xIS0N1AZa9

— Times Higher Education (@timeshighered) September 10, 2022

This crisis simultaneously threatens to unwind the progress made by various social mobility organisations. The English graduate, who in 2021 was awarded two student social mobility awards, is also anxious that the volatile economic environment threatens to further instil a lack of confidence in students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds about their futures.

‘We have been telling students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds for years that they should aspire towards any path they wish to after leaving school, whether that be in higher education or employment, and that personal finances will and should not act as a barrier to this because universities offer bursaries, scholarships, and students can apply for the maximum maintenance loan if their household is below a certain income threshold’.

The balance of opportunity is still invariably tipped towards those from more advantaged backgrounds

‘The main goal of social mobility organisations that help students is to boost confidence, create a sense of community, and encourage students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds to reach their full potential. But when we're living in a world in which nobody seems able to reach their potential because they're too stressed about finances, this hits them even harder. There is an apparent veil of cynicism in the air at the moment and this is eating away at all the hard work that charities have put into creating optimism in the young people they support’.

This too brings into sharp focus questions concerning the status of higher education as a meritocracy. For less financially secure students, it remains a comforting thought that grades and talent should extinguish class divides and shield you from prejudice and stereotype. You would be forgiven for believing that ability and determination warrants access to the same network of opportunity as everyone else.

Do all students have 'the same 24 hours in a day' at university?

Does Bristol's reputation for social exclusion stand up to the scrutiny of statistics?

But University is not necessarily a social leveller nor an equal playing field; a student from a disadvantaged background who gains a first-class degree from a high-ranking university is less likely to secure an elite job than a more privileged student with a 2:2. The cost-of-living crisis is poised to further stack the odds against students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, entrenching the societal obstacles that prevent them from achieving upward social mobility. The balance of opportunity is still invariably tipped towards those from more advantaged backgrounds.

In regard to mitigating the detrimental impact of the crisis, Ms. Bingham-Roberts suggested that the University of Bristol put in place additional support for students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds. She recommended that ‘students who receive bursaries should receive one-off payments in October to off-set the increased prices they are about to experience, especially those in private accommodation who directly pay energy bills themselves in addition to rent. The University already has the data on who is most in need, they just have to use it’.

Featured Image: Flickr / Graeme Churchard

What do you think the University of Bristol should be doing to offset the impact of the cost-of-living crisis?