By Xander Brett, Travel Editor

The Croft Magazine // A vast journey from Cape Breton (Nova Scotia) to Vancouver Island (British Columbia) saw a thief onboard and a dragon from Quebec.

An announcement chimed up. The train was delayed. I left my seat, exited the terminal and was bowled over by a gang of hockey fans. I’d travelled down from Montreal in the morning, had lunch, then ascended the CN Tower. I arrived at Union Station with hours to spare, desperately paranoid I’d miss the trip of a lifetime. ‘The Canadian/Le Canadien’, travelling from Toronto to Vancouver, passes through five provinces. Connecting Canada’s east and west, it’s one of the world’s great trans-continental routes. I was completing the stripe, heading across the Midwest to Victoria. It was a 6,051km trip from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

I boarded later that evening, settling down on two chairs: my bedroom for four days. I was handed responsibility of opening the doors (it seemed jobs were shared among staff and passengers). A Frenchman struggled in with bags and bad English. As the sun rose, we made our first stop in northern Ontario. It was late October, but the snow was already thick. From there, it was on to Winnipeg. We’d arrive in two days, so it was time to settle down. Meals were taken in the dining car. This was at the rear of the train, leading to a balcony at the far end. Tables seated four and, as most of the few hundred passengers were travelling alone or in couples, this was where the many train classes and nationalities came together. In the afternoon, one returned to quarters for a short rest, then chatted in the glass-roofed Skyline car until dinner.

We were given time off in Winnipeg for a walk around town. When we reboarded, within the hour reports were circling that a thief was onboard. Sadly, it didn’t take Inspector Poirot to deduce the culprit was young indigenous guy. He’d been stealing phones, hiding them in a woman’s shoe. To divert attention, he’d rummaged through every seat, feigning he’d lost his own. We ground to a halt at a small tumbleweed settlement called Rivers, sitting in the shadow of a large grain stack and entirely surrounded by vast prairie. The police boarded, took statements, and told us there’d be a unit in Edmonton to take him away. The guy said he’d made many enemies across Canada. He was a wanted man and had climbed aboard without a ticket, hoping to stow himself away. Instead, he’d sensed opportunity. He couldn’t resist criminal urges. It was a story shared by so many in his community. On these rural reserves, non-aboriginal Canadians earn 88 per cent more than their indigenous neighbours, and over 60 per cent of crimes are by First Nationers.

At Winnipeg, the train crew changed. The nice Ontarian attendants were replaced by a fat one and a dragon from Quebec. I’d been taking showers in second class (third class had only a sink), and the new crew weren’t going to let it go. They checked my bags as I crossed the divide. I revealed a layer of books, concealing a towel. “Just some reading for breakfast,” I lied. The dragon took up position. “How dare you,” she hissed, rounding the corner as I left the bathroom. She screamed, demanded $90 in cash and, when politely asked where it would go, shouted so loudly I saw no way out but to cry. There’s nothing more embarrassing – or useful – than the sight of an 18-year-old boy sobbing. Within seconds, the train’s multi-millionaire was on hand. Word got around. My fellow passengers joined a quest for class struggle. An uprising was imminent, but we agreed to put it on hold. Instead, I was given breakfast by the rich dude (he gave a $20 tip to the waiter for putting “nice milk” in his coffee), dodged a Halloween sweet (thrown at me by the fat woman), and had my position as ‘door safety warden’ removed.

As we pulled into Pacific Central, we were reminded of this train’s importance. The line took four years to build, and to this day remains predominately single track. “Thank you for being with us,” said the attendant over intercom. “We know it’s a trip our visitors come from all over the world to complete.” Emerging into Vancouver – Canada’s ‘other half’ – we said our goodbyes and dissolved into the streets. I took a Skytrain to the ferry port, missing the boat by seconds. No matter. I’d caught my first glimpse of the Pacific and could board the next ferry, catching a lift into town with a young naval officer. When I arrived in Victoria and climbed into bed, I reflected on the expanse I’d covered. I’d traversed North America. I’d seen the wastes of Ontario, the plains of Manitoba and the mountains of Alberta. In two days I’d be in Seattle, seeing the other side of the United States. It had been an epic journey, and Canada had been conquered in the process.

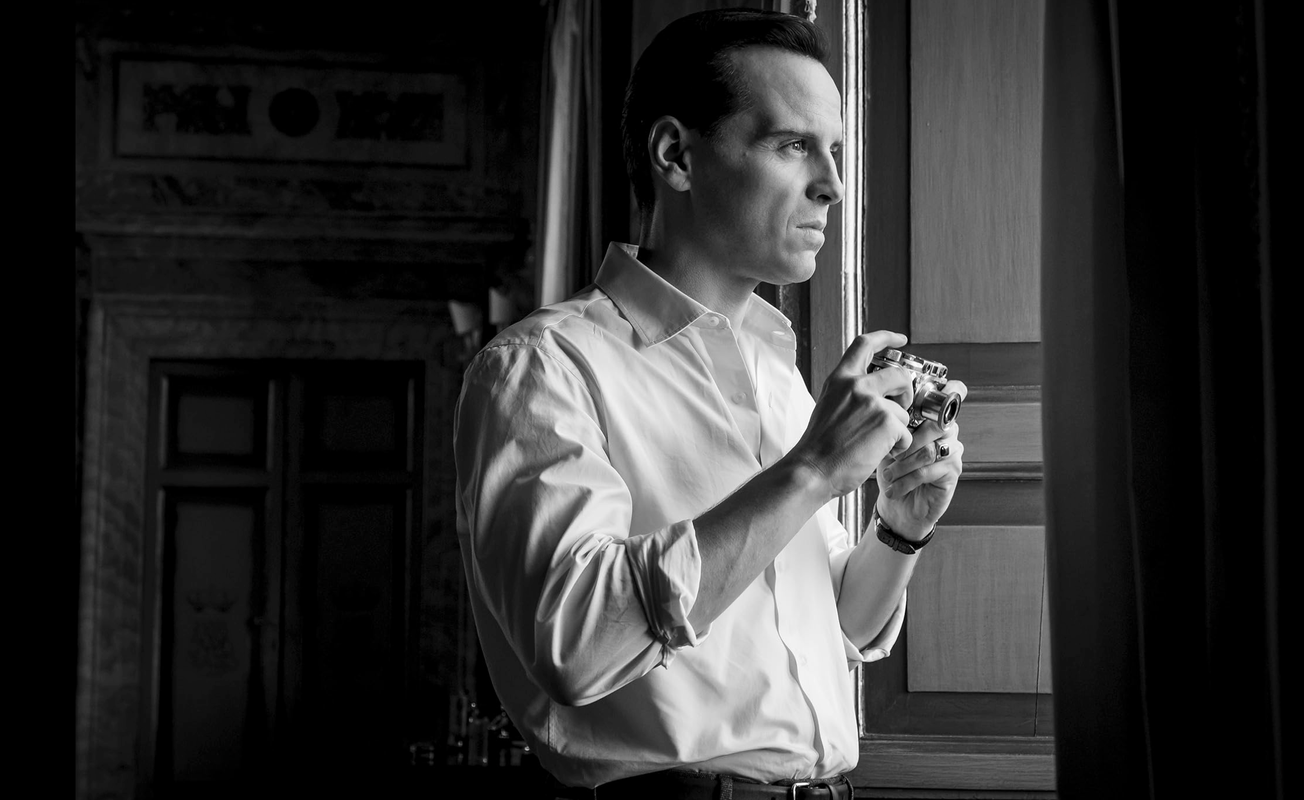

Featured Image: Epigram / Xander Brett