By Meerabai Kings, Fourth Year, Biology

The origin of the immeasurable diversity of plants we see today has been unearthed by the discovery of a ‘life giving’ fossil. The last meal of the 98-million-year-old insect shows that plants owe their biodiversity to ancient plant-pollinator relationships.

Flowering plants (angiosperms) are the most diverse group of plants on the planet. The roses in your vase, the rice you had for dinner, the oak tree in your local park, the cactus on your windowsill; they are all angiosperms. These four plants alone offer a far greater biodiversity than the group of non-flowering plants (gymnosperms), including yew trees and pine trees. 80 per cent of plants on Earth are flowering plants, and some palaeontologists put their widespread success down to the help of insect pollinators.

The importance of insects in the success of flowering plants has been highlighted by research at the University’s School of Earth Sciences, in collaboration with the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NIGPAS).

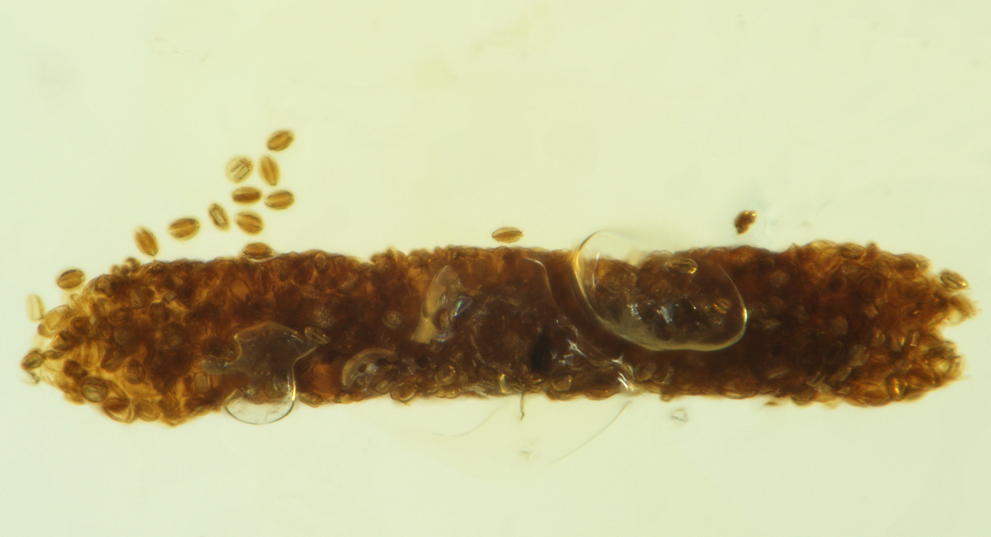

The research is the debut of prehistoric pollinator Pelretes vivificus (above), a 98-million-year-old beetle from Myanmar. Vivificus lived in forests during the Cretaceous period and was found exceptionally well preserved in amber, the fossilised sap of ancient trees. This would not be dissimilar to getting stuck in a vat of maple syrup that solidified over 98 million years, keeping you in a clear and airtight nugget.

‘Some aspects of the beetle’s anatomy, such as its hairy abdomen, are adaptations associated with pollination’ said Professor Chenyang Cai, from the School of Earth Sciences and NIGPAS. A hairy body acts like Velcro for pollen grains to stick to and get transported to its next destination (which modern insects like the bumblebee also possess), which certainly hints at Vivificus being a busy pollinator.

Shedding droppings and light

Vivificus itself is a very exciting discovery, yet even more exciting is the beetle’s droppings! Vivificus was found surrounded by two coprolites (pictured above) – which are pellets of fossilised faeces. Analysis of the coprolites revealed them to be laden with golden nuggets of pollen, providing a direct link between prehistoric insects and angiosperms.

This single Vivificus fossil is the fifth prehistoric pollinator to deliver such strong evidence of ancient plant-pollinator relationships. This new finding is an evidence goldmine, as the only insight palaeologists have into these ancient relationships are rare amber deposits. To find such compelling evidence is infrequent and remarkable!

Before the Cretaceous period, over 200 million years ago, the planet was as green as we see it today, but the plants were less diverse. In the mid-Cretaceous period, coinciding with Vivificus’ lifetime, flowering plants began to diversify and evolve. This could mean that insects such as Vivificus allowed the diversification of angiosperms, by providing an easy way for them to spread their DNA and dominate thus the plant kingdom. Pollination is, after all, the transfer of one plant’s sex cells to another.

This phenomenon is called coevolution, when two species simultaneously evolve to, in this case, complement each other’s survival. You see as insects visited more plants, plants were able to breed with each other more to produce weird and wonderful forms. As plants diversified, insects became specialised plant visitors, fine-tuning themselves to collect pollen. Their Velcro-like bodies being just one adaptation of many!

What next for Vivificus?

The University’s research with NIGPAS gives compelling evidence that Vivificus evolved hand-in-hand (or leg-in-stem) with prehistoric angiosperms. Vivificus is Latin for ‘giver of life’, referring to the vital role insects play in the reproduction of flowering plants.

‘While the fossil sheds light on the origins of pollinators of flowering plants, many insects had mutualistic associations with plants before the Cretaceous’ said Erik Tihelka, undergraduate at the University of Bristol and leading palaeontologist on the research.

Tihelka hopes the discovery of Vivificus will inspire research into earlier fossils: ‘We are curious about exploring the earliest pollinators, with the help of fossils from even older exceptional Mesozoic fossil deposits.’

Honey: The golden resource shedding light on ancient civilisations

Conservative crocodiles outshone by their ancestors

Perhaps with this knowledge of how insects have led to the success of our favourite plants, concern will be raised about the decline of our insects to pesticides. How can we expect plants to thrive without the pollinators they have spent millions of years relying on?

If you’re itching to read more about Vivificus, you can do so in this research paper by Tihelka and colleagues.

Featured Image: NIGPAS & UoB / Chenyang Cai

Next time you see some old-looking faeces take a closer look. Who knows? It could be a paleontological goldmine!