By Flossie Palmer, Features Editor

Going unnoticed is a common experience for those with hidden disabilities – after all, they are ‘non-visible’ conditions, and are therefore difficult to identify. However, 11.2 per cent of students in the academic year 2021/2022 have a hidden disability, making up over a tenth of the student population, including those with: social or communication impairments, mental health conditions, cognitive or learning disabilities and sensory, medical or physical impairments.

Whilst there are many students at Bristol who have hidden disabilities, awareness of these is often incredibly low, with students reporting feeling a lack of safety for their own wellbeing on campus and around the city more generally.

In November 2021, I experienced what I could only describe as an act of discrimination. The security staff at a well-loved local bar began to refuse me entry on the grounds that I did not have a GP letter on my person as proof that I could carry my blood testing kit – something I rely on daily to monitor my Type 1 Diabetes. The five-minute wait – spent holding up the queue demonstrating to the security staff how to use my testing kit and showing that my insulin injection needles are sealed - was the most humiliating and unwelcoming experience of my entire 14 years as a Type 1 diabetic.

Eventually I was admitted into the bar and spoke to another member of security who disagreed with the actions of his colleague. I later filed a complaint, to which the bar responded that I was ‘searched in accordance with [the bar’s] policy which has been heightened with the current threat of spiking in the hospitality sector. When medical equipment was seen in your bag, it was clear that it needed to be questioned.’

Although this precaution is understandable to protect the safety of the wider population, I felt completely demeaned and was made to feel unacceptable in front of a bustling queue for a medical condition which people cannot see, let alone understand. After breaking down in tears, I exited the bar within a few minutes, left with an email apology to follow and a feeling of complete isolation within my own body. This then prompted the question: have others had similar experiences?

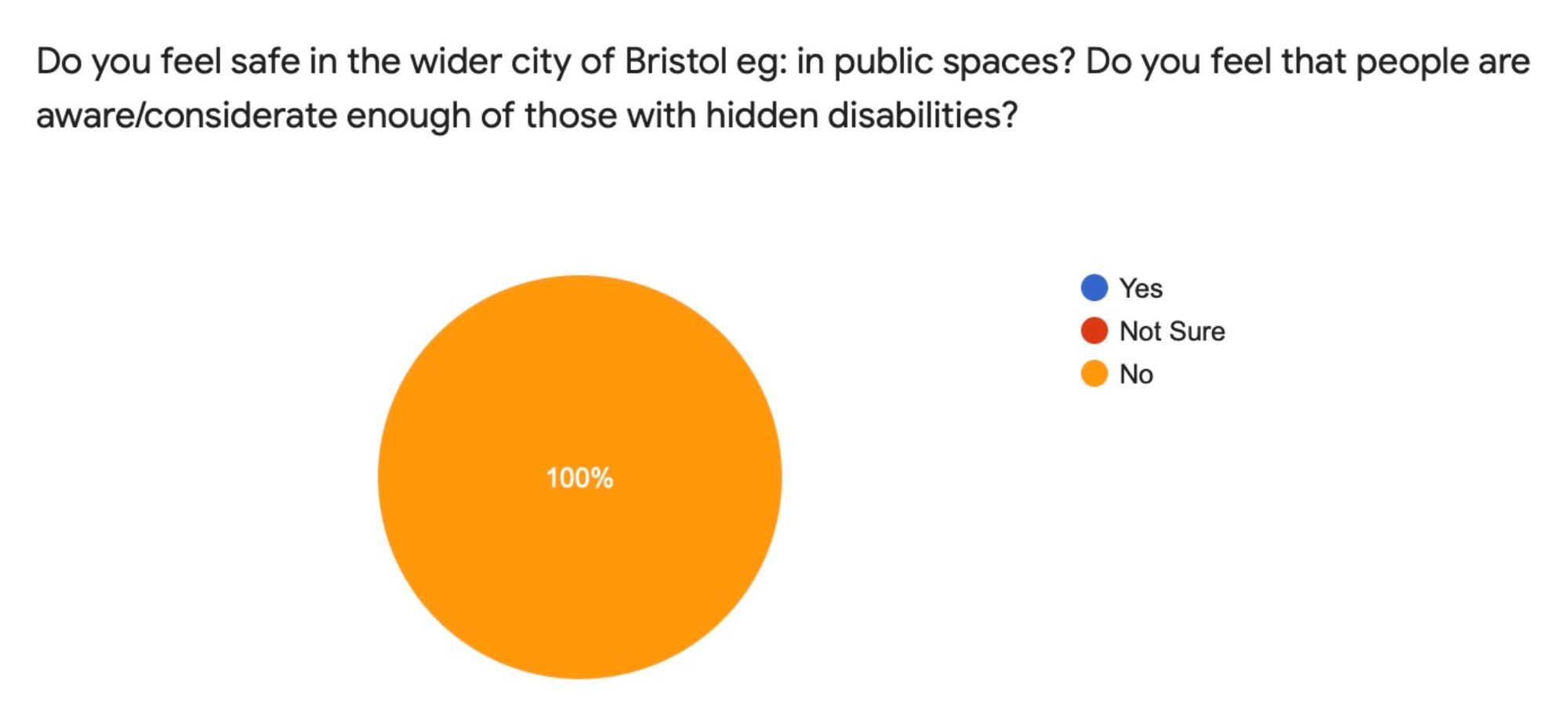

In a recent survey, Epigram found that all respondents with hidden disabilities, do not feel safe in the wider city of Bristol, such as in public spaces. Third year English student, Thea Powell, who has temporal lobe epilepsy, agreed, stating that; ‘I know that my housemate and my parents worry that [I’ll have a seizure] when I’m out. Nobody would really know that I was having an epileptic seizure because if you see someone sat on the side of the street looking dazed and confused, you’d just think they’ve gone crazy.’

Thea also explained that a greater awareness and recognition of those with hidden disabilities is needed, stating that ‘It is not just the disability that is hidden, but the crisis moment too.’

The Sunflower Scheme, first launched in 2016, has established the symbol of the sunflower as one representative of those with a hidden or non-visible disability. Those with a hidden disability can pick up a sunflower lanyard and wear it in public spaces to discreetly inform those around them that they have a non-visible condition, and may require more time and consideration, without having to verbalise this. On the surface, this may improve awareness in a way which avoids the draining process of verbal explanation. However, it poses the question: should it be the person who has the non-visible disability’s duty to educate others?

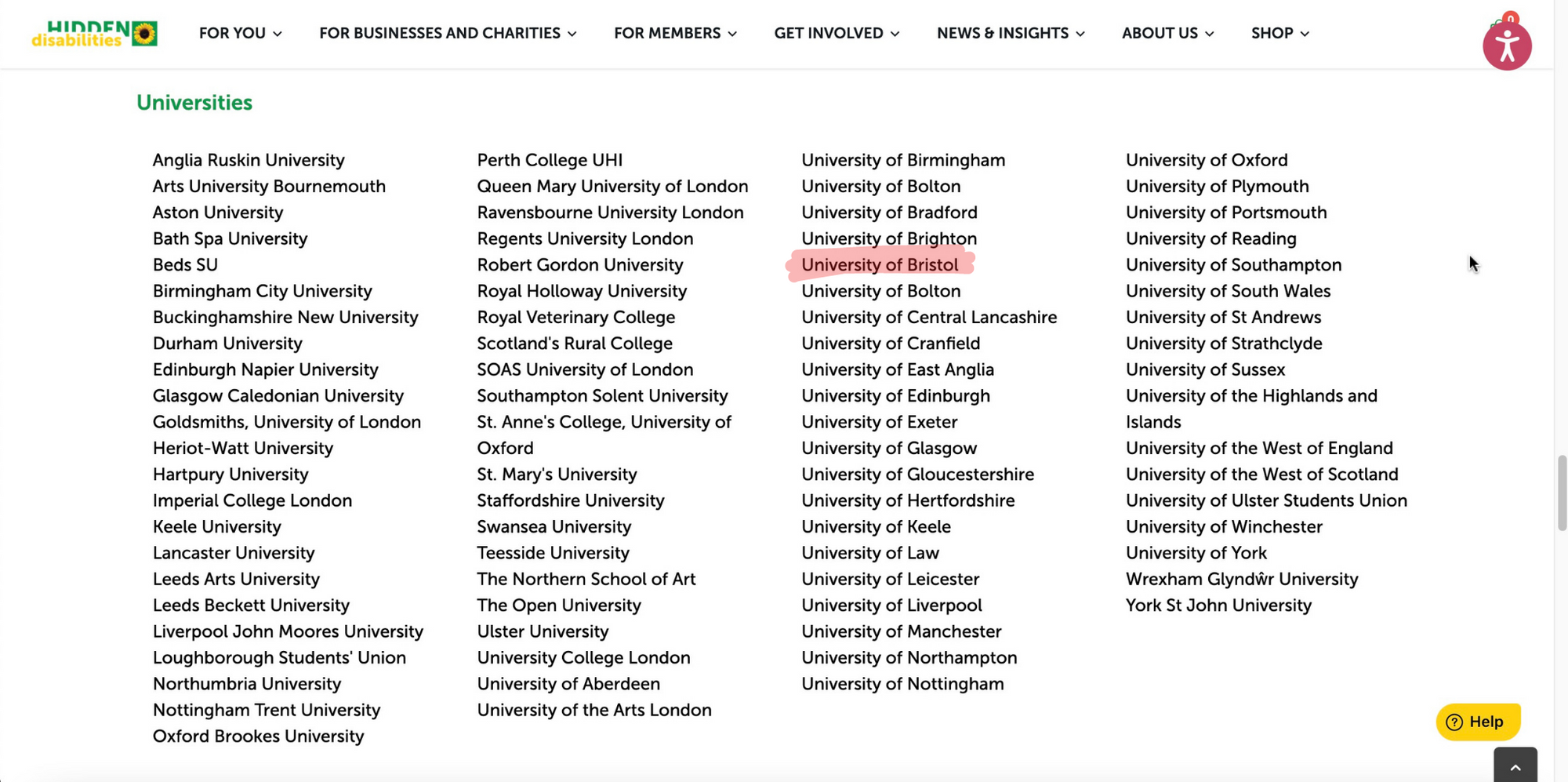

On the Sunflower Scheme website, the University of Bristol is listed as an affiliated institution, meaning that students can collect sunflower lanyards from their Equality and Inclusion Team on campus. However, after enquiring about the University’s involvement in The Sunflower Scheme, Bristol SU, Bristol SU Disability and Accessibility Network and the Disability Services could not provide any information - such as where students can collect a lanyard on campus - about the University’s co-operation within the Scheme.

So, just how aware of hidden disabilities is the University of Bristol?

There is no doubt that the University’s Disability Services goes above and beyond to provide support for its students during their time at Bristol. All disabled students at the University are entitled to support and reasonable adjustments to assessments and exams, for example. Once the Disability Services receives a referral, students will receive an appointment with a disability advisor who helps them create a personal disability support summary (DSS) – a document about the student, their needs, and suggested changes to assessments – which is then shared with their School.

This is also available for students with hidden disabilities as well as those with visible disabilities and saves students the difficulty of having to voice their struggles or flag their need for extra help or consideration. Students who feel they do not need an appointment with a disability advisor can also apply for alternative exam arrangements (AEAs) themselves. The Disability Services also offers support for students when applying for funding such as the DSA, the Disabled Students’ Allowance, which can help students procure the special equipment, alternative transport or extra assistance they need to carry out their studies.

Holly Bailey, a Senior Disability Advisor at the University’s Disability Services, told Epigram that the Disability Services also offer a series of workshops which students can attend. These include: study skills workshops aimed at students with specific learning difficulties, such as dyslexia and dyspraxia, ‘Am I Dyslexic?’ workshops which help students identify their difficulties and seek a referral route, as well as post-diagnosis sessions for those newly diagnosed with a learning disability.

When asked if they felt satisfied with the support the Disability Services had provided them, all respondents to Epigram’s survey agreed, with students highlighting the range of assistance the Services provided them with, from help with accommodation accessibility to simply putting them in contact with the right person.

However, although in the academic year 2021/2022, there have been 4, 455 total students identified as having a disability, 2.5 per cent of the student population are still not known by the Disability Services to either have or not have a disability.

Holly posed the theory that this could be due to students feeling ‘uncomfortable’ with the term ‘disability,’ stating that ‘I think sometimes what might put students off coming to Disability Services is potentially the term ‘disability.’ She recognised that ‘Conditions such as dyslexia to chronic fatigue syndrome to ADHD to depression - they are all disabilities, but some people might not consider themselves disabled.’

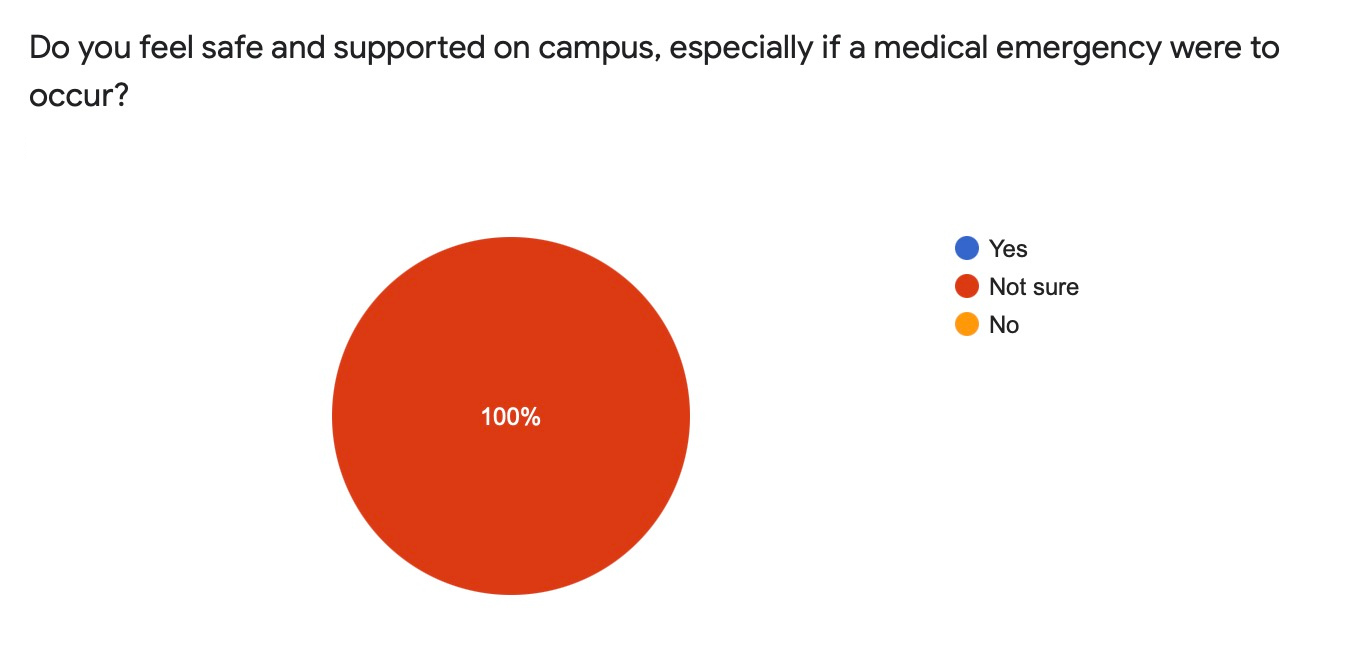

While it seems that the Disability Service is a primary hub for providing support for students known to have a hidden disability, 100 per cent of students who responded to Epigram’s survey reported that they were unsure of whether they felt safe and confident that others would assist them on campus if a medical emergency were to occur. These responses were largely given due to the perceived lack of awareness students felt about hidden disabilities on campus.

Lucy Chippett, a preliminary year Physics student who suffers from chronic pain, told Epigram about the judgement she has faced on campus for her condition; ‘I’ve been made to feel shamed around campus for needing to take the lift as I don’t look physically disabled.’ She further explained, ‘There are signs around the physics building telling you to burn calories and not electricity by taking the stairs, which makes me feel guilty for needing to take the lift and is also an upsetting choice of words for someone who has previously suffered (and still somewhat is suffering) with an eating disorder.’

Lucy related that on another occasion in the geography building, a member of staff approached her waiting for the lift and advised that it would be a better and quicker option for her to take the stairs. ‘I told him I had a disability, to which he replied “oh, there’s something wrong with you” and walked off. This was very upsetting and unsettling,’ Lucy explained.

One anonymous student reported sharing a similar experience; ‘I have been told by staff that I shouldn't use the 'wheelchair lift' because it's only for disabled people. It wasn't malicious and they apologised, but it's still a horrible feeling. I live my life afraid of being called lazy or a liar every time I leave my house, and it would be good to feel that campus is a safe space at least.’

They added that; ‘I think that staff should be trained to understand that hidden disabilities exist and not to prejudge someone based on assumptions. For example, not all of us use mobility aids, and some people use them occasionally - this doesn't make us less disabled.’

When investigating University staff awareness of hidden disabilities, Epigram found that although staff are encouraged to undertake training sessions regarding hidden disabilities, only one of these courses is mandatory regarding mental illness awareness, while the rest remain voluntary. Personal tutors also have access to online resources surrounding hidden disabilities, but these are self-serve optional resources rather than training courses.

Helena Thornton, Chair of the Bristol SU Disability and Accessibility Network, is working with her committee and Bristol SU to ensure wider awareness is raised across campus concerning both non-visible and visible disabilities. ‘We act on what needs to be done,’ she told Epigram, sharing how students who are facing obstacles while at university can contact the Network and be put in touch with the relevant people to reach a solution.

One of the most recent difficulties that Helena has dealt with in her role as Chair has been the University’s transition to ‘blended learning’ post-Covid, which has caused confusion when adjusting to students’ requirements, especially with in-person assessments.

‘Covid-19 brought some problems and solutions in terms of learning for disabled students,’ Helena acknowledged, ‘In some ways, having online learning was so much more accessible, and when the University invested in infrastructure to bring learning online, students were able to do it from home where they were having flare ups and mobility difficulties, and that made such a big difference. But then there were other issues which students had, often through disability, which meant that online learning had been a nightmare!’

One student, who has autism and processing delay, told Epigram of their difficulty adjusting to online learning during the academic year 2020/2021; ‘There have been a few challenges, especially regarding trying to access subtitles during online sessions.’ It took the student six weeks to have their tutors switch to Microsoft Teams so that they could access subtitles which enabled them to process information more easily. The student now believes that accessible remote learning platforms should be used as a default to accommodate for students of different levels of ability.

Another student, who struggles with multiple chronic illnesses, including chronic fatigue, PoTS and fibromyalgia, elaborated on their experience adjusting back to in-person learning, highlighting the need for ‘basic accessibility without having to ask’ while on campus.

This encompasses: ‘always having enough chairs in a room, allowing students to use laptops and eat/drink without having to disclose personal medical information first, automatically putting CC on videos, not questioning why someone is in an accessible toilet if they aren't in a wheelchair…’ The student stated that, ‘All of this applies to everyone, but staff should be trained to understand and recognise these things.’

So, how can the University its improve its consideration of those with hidden disabilities?

In Helena’s view, it starts with basic awareness and inter-personal relationships; ‘I think a lot of it is about awareness and a campus culture,’ she began. ‘I think because there is such a wide range of invisible disabilities and different impairments that people face, awareness needs to be improved at a student level and at an academic level,’

‘There also must be understanding of what is needed to shape policy rather than a policy being created with able-bodied people in mind and then every so often a disabled person struggles with it, faces an issue, and it’s solved on a case-by-case basis.’

However, Helena also recognised that, ‘It’s also difficult because there is such a wide range of disabilities that it’s hard to suggest that people understand a blanket sense of accommodation.’ As Helena stated, ‘just because I appear fine, it doesn’t mean I’m not experiencing difficulties,’ which, when there is a lack of awareness, allows people to make so many presumptions, most of them often incorrect.

In addition to the Disability Service, Bristol SU remains committed to ensuring the safety of students with hidden disabilities on campus. Leah Martindale, the Bristol SU Equality and Liberation Officer, released a statement supporting her dedication to student wellbeing;

‘Supporting students with hidden disabilities is really important to me and there’s a lot of work that I’ve been doing to help improve their experience. As an officer team we’ve been working with personal tutors by producing guides for working with different students including those with hidden disabilities and with autism spectrum disorders.’

‘Alongside our Disability and Accessibility Network Chair Helena, I’ve delivered training to SU staff on hidden disabilities and to increase a culture of self-auditing to improve the services we offer to students. We’ve also both been part of a university task and finish group to deliver a student perspective on how the university can improve the experience of disabled students.’

73 per cent of students feel University extension policy must change regarding mental health

‘Medical schools are treating eating disorders as a niche subject': raising awareness this EDA Week

It is undeniable that the negative experiences of students with hidden disabilities either slip past the University’s radar or are dealt with on a case-by-case basis, often involving a long and emotionally draining process for the student involved. However, bodies under the University umbrella, including Bristol SU, Disability Services, the Bristol SU Disability and Accessibility Network among other student societies, remain committed to ensuring the safety and visibility of those with hidden disabilities in the face of support services.

While progress is continuously being made University-wide and beyond campus towards acknowledging the non-visible needs of others, the first-hand accounts students shared with Epigram prove the immediate need for awareness and at the very least, greater consideration for others.

Featured Image: Epigram / Cameron Scheijde

How do you think the University can improve its awareness of hidden disabilities?