By Annie McNamee, Features Digital Editor

I first read The Bell Jar when I was seventeen, having been recommended it by my English teacher. I finished it in about two days and I cried. A lot. A month later I would discover Phoebe Bridgers, Fleabag, and Emily Dickinson, all at once. If these names are at all familiar to you, the expression you are looking for right now is: ‘Jesus Christ.’

I am, shamefully, a sadist when it comes to art. You just read a book where nothing happened other than a wistful protagonist being sad and annoying? I’ve already bought, read, and rated it five stars on Goodreads. I am not alone in this inclination toward the sombre; the most translated text of all time (other than The Bible) is The Little Prince, a story so upsetting that my mum couldn’t even finish reading it to me as a child. Shakespeare’s tragedies are known by and adapted for far wider audiences than his comedies. Clearly, we love things that make us feel like rubbish… at least, sort of.

We will always be drawn to that which evokes strong emotions, and it’s just unfortunate that bad feelings tend to stick with us for longer. Art can help us to process real difficulties; crying for a character experiencing something you can relate to is a way of letting that sadness out without really thinking about the problem, like a sort of controlled explosion. We find comfort in knowing that someone else has been where we currently are, and that they made it through. Not only that, but they turned it into something beautiful.

So, we love stories that hurt - real ‘the film finished twenty minutes ago and I’m still crying’ gut punches - and we love the people who made them, especially when we can tell the stories come from the heart. The ‘tortured artist’ is a familiar trope; this idea that really great art comes from people who are properly f***** up. In an artsy way, obviously. This artist’s muse is their own mind, and we’re lucky to gain insight.

Woolf. Van Gogh. Hemmingway. Kurt Cobain, Elliot Smith, Ian Curtis, and of course, my very own Sylvia Plath. It is easy (and correct) to idolise these people for the works that they created, but the step from enjoying the melancholic to conflating it with greatness is treacherous. It can seem logical to conclude that to make great things one must first suffer biblical levels of anguish, or, more dangerously, that there is something inherently artistic in being unhappy.

Sylvia Plath died aged 30. When I read The Bell Jar at seventeen, I understood this to mean that if I wanted to write like she did, the trials I was facing were part of the package. That if I could struggle just enough in just the right way, I’d eventually make something worthwhile. Plath’s mental health, while the subject of much of her work, also robbed the world of decades worth of poetry and prose. There’s no romance in that loss.

I read in an article that whilst performing at one of her concerts, Phoebe Bridgers, sad girl extraordinaire, explained that her saddest songs were not written at her darkest periods. ‘I use music to reflect…I guess I’m trying to say it gets better’. Reading this, I almost understood how Joan of Arc felt when she first heard from God. It was a sudden realisation: these works don’t exist because their creator struggled, they exist, persist, in spite of it. They exist because despite all that was wrong, these people had hope that they wouldn’t feel that way forever. They were motivated by their love of creating, their desire for connection.

Let’s stop doing these great artists a disservice. Those who managed to turn their worst nights into iconic, thoughtful pieces would not appreciate us remembering them for how they died, rather than all that they did whilst they were alive. Don’t aspire to be the next great tortured soul. Take inspiration from their determination to fight while they could. And if you are planning on reading The Little Prince to a child anytime soon, practice first. Trust me, ugly-crying in front of a toddler is a humbling experience.

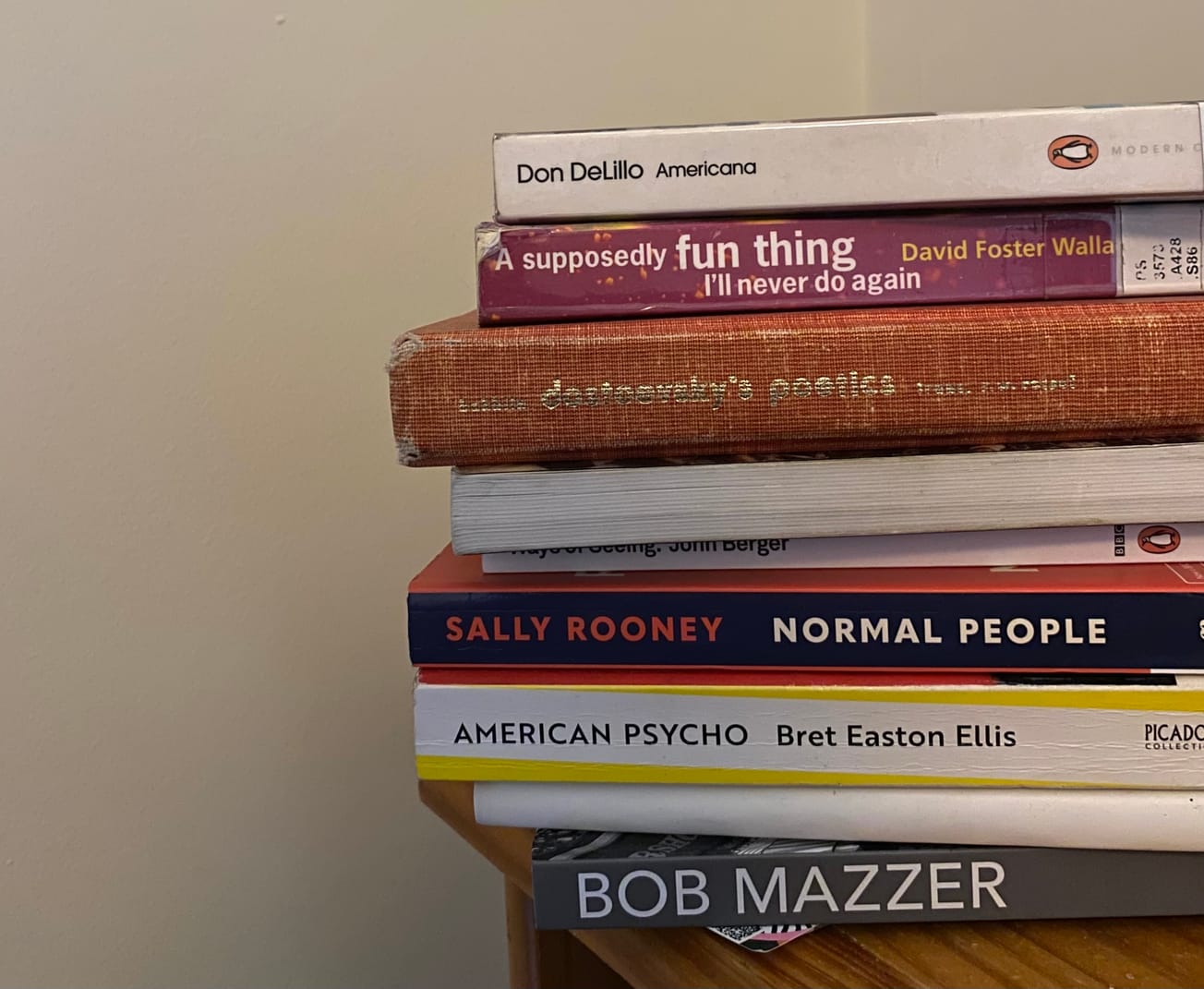

Featured image: Redd F / Unsplash

How do you feel about the trope of the tortured artist?