By Jacob Rozenberg, Second Year, English Literature

Noah Baumbach doesn’t really do adaptations. His first, in over 27 years since his debut Kicking and Screaming (1995), might make you wonder why it’s been so long a wait. The tricky terrain of White Noise (1985), Don DeLillo’s eponymous novel, feels like a familiar fit for the writer-director.

Familial conflict, anxiety-leaden characters, deliberately rhythmically obtuse flows of overlapping dialogue – many of the elements of DeLillo’s work feel opportune for a Baumbachian script. For a director whose work often feels adjacent to the literary, Mr. Jealousy (1997), and poking at the strains of married, domestic existences – While We’re Young (2014) and Marriage Story (2019) – on paper he should feel right at home with the postmodern quandaries explored in his chosen source material.

White Noise’s (2022) three distinct acts detail the life of Jack Gladney (Adam Driver), an acclaimed college professor of Hitler Studies, and his attempts to hold together his fractured family before, during, and after the interference of an Airborne Toxic Event.

Any reader of DeLillo will recall the idiosyncratic nature of his hypermodern, affected dialogue: conversations which blur distinctions between high and low culture, characters’ examinations of the signs and symbols of consumer culture, and a sense of people constantly searching for fulfilment and meaning in their lives, nonetheless.

Scenes depicting the family breakfast time incorporate DeLillo’s tapestry of conversation, with each family member’s grievances of different topics layered over one another in the sound mix, echoing the sense of cultural overload which the novel possesses.

One unforgettably verbose scene sees this same lack of distinction between high and low cultural topics through an academic battle on the assessment of the early life of Icons; from Gladney, on Adolf Hitler, and his opponent Murray Siskind (Don Cheadle) on Elvis Presley. It is far funnier than can be expressed in this article.

The film’s set design acts as a living embodiment of consumerist 1980s America. Baumbach and cinematographer Lol Crawley shoot the Gladneys’ local supermarket in a way presumably inspired by Andreas Gursky’s 99 Cent (2001), lines of seemingly infinite meticulously-stacked shelves stretching into the distance – the supermarket as the church of modern America.

Greta Gerwig is Babette, Gladney’s wife, who provides the emotional and existential core of the film. Babette’s addiction to Dylar, a drug which is said to numb the pain of modern life, is depicted with nuance by Gerwig, displaying the character’s feelings of emptiness shared by many other neurotic Baumbach protagonists.

White Noise truly feels like the director is challenging himself, particularly in his depiction of the Airborne Toxic Event, which powerfully recalls both the impact of natural phenomena on our world and the not-too-far-away time of the COVID-19 pandemic. The series of events which take place in the denouement make White Noise feel considerably more epic than most of Baumbach’s other works.

Whilst much of the book’s story is left unchanged, the added addition of a certain character to a crucial scene near the end of the film shows how Baumbach is unafraid to briefly alter the course of the narrative in order to land a stronger conclusion.

Ultimately, however, as successful an adaptation as White Noise is, in its director’s wider body of work, it is exactly that: an adaptation. Having already loved the novel, one can feel affirmed that Baumbach has done the work justice – but, while watching – one is constantly reminded that this is not original material, and thus, paradoxically, what bars this from being among his greatest work is also what makes it succeed.

As exceptional as the source material is, at the end of the day, it is still only an adaptation. That said, it is one adaptation very much worth watching.

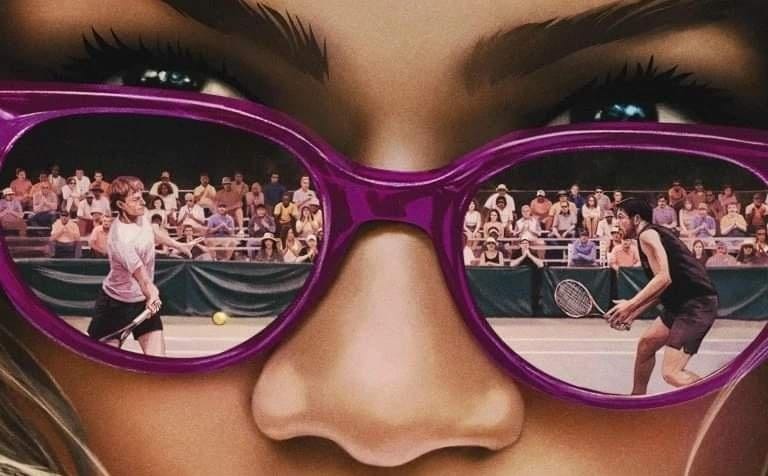

Featured Image: Photo by Wilson Webb/Netflix, courtesy of IMDB

Do you think Baumbach did the novel justice in the film adaptation?