By Ellie Spenceley, First Year English

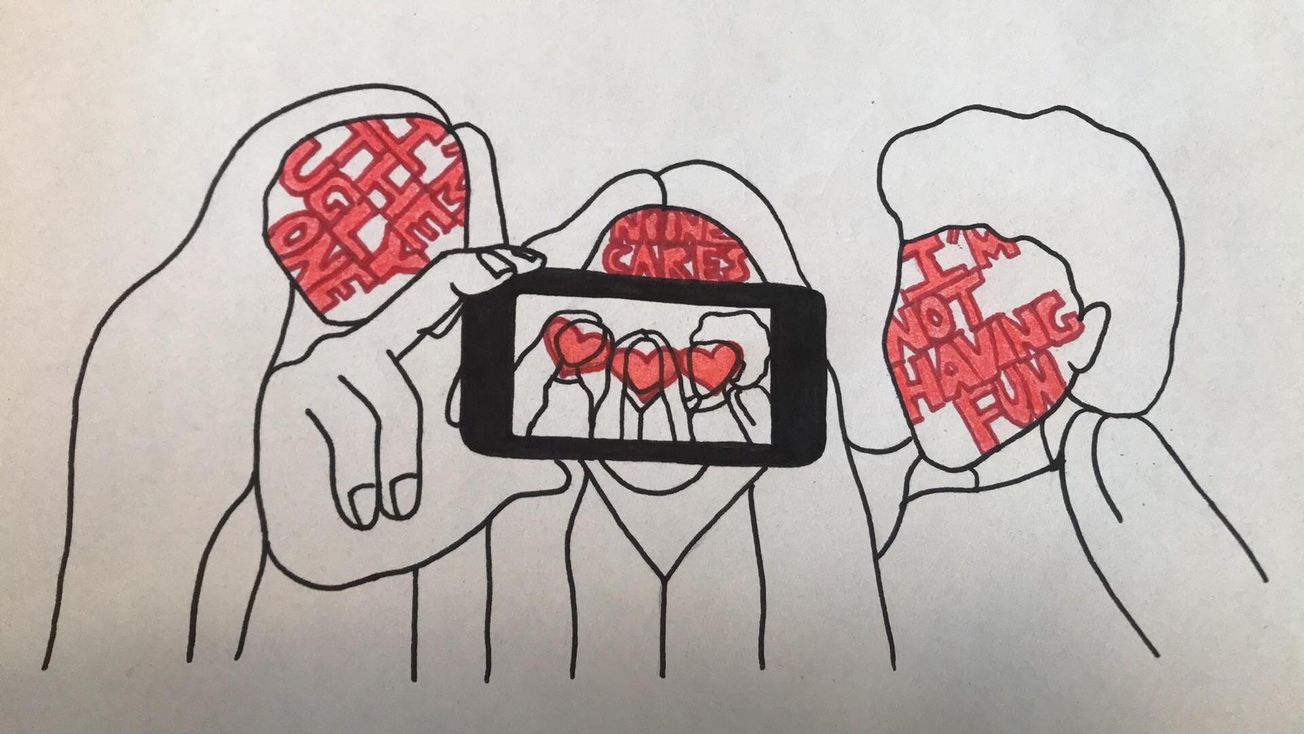

The Croft Magazine // We’re so caught up in the digital world that we forget that it’s nothing but a rose-tinted reflection of the real one we have to live in each and every day.

Our online space seems to have become our central reflection of personality, and it’s not hard to see why we find this so alluring: Instagram allows us to curate the image we want people to see and makes us feel a sense of control we simply don’t have in reality where unfiltered candour is the only thing we’re able to show.

Criticising the visual culture we’ve become naturalised to is an easy way to appear ‘woke’, but there are few of us who are immune to the instantaneous dopamine hit of the like, the pang of validation that hits when someone you like ‘likes’ that selfie you thought you looked good in, the sense of social capital you feel when your post gets a certain amount of likes, when someone slides up on your story, when you feel seen in a society that has a tendency to overlook.

Social media makes us feel acknowledged and important

The double tap has become instinctual, so much so that we often don’t even take a moment to look at what it is we’re claiming to like. Ironic is it then to realise that we depend so heavily on the validation that comes from something we ourselves provide so absentmindedly.

We’re all on some level aware of the divide between social media presence and the person we, and our friends, really are, but it seems we are all hesitant to entirely distance ourselves from a world of instant gratification.

When the whole of your academic cohort is in your pocket, your social circle feels expanded, and when they like your post you feel like they like you. I know personally how good it feels to post something and have an instant flood of recognition, and I’m guilty of the perpetual refresh, indulging in the addicting feeling of seeing the like count go up.

My first term at university was an overwhelming and often isolating experience, but having followed practically everyone on Instagram through Facebook group chats before I arrived, it felt like ‘I know you from Instagram!’ was my saving grace.

Now I’m in my second term, I do know a lot of these people more in reality, and I’m undeniably grateful that an online medium could do the icebreaking I’m often reluctant to do in person, but it’s no doubt a pressing issue that hyperconnectivity has arguably made us less connected in reality, with the assumption that a follow is equal to a friend being a dangerous one.

A popular social media profile can often intensify feelings of loneliness when you realise the people who see you online don’t know anything about you in real life.

While the dopamine hit that a like provides us can feel good, it’s a high that has us addicted, and addictions tend to be insatiable. With Instagram validation, the more you get it, the more you want to receive it and maintain it, and the more you want it in greater abundance.

I remember in sixth form when 100 likes was a feat for me, and now 150 seems ‘low’ in comparison to the numbers I sometimes hit. The positives we reap from a fruitful social media presence trigger a reward cycle where we’re never truly satisfied with the response we receive, constantly comparing ourselves with those receiving more attention, whether they are a celebrity or someone you sit opposite in a seminar.

Instagram seem to be aware of this issue and have dabbled with the idea of hiding like counts from other people’s posts and only enabling you to see your own, a solution that would perhaps end numerical comparison.

Social media can no doubt be a force for good. Used consciously and with enough self-awareness, it can enable us to create a space that allows us to thrive emotionally and intellectually, benefiting daily from a wealth of knowledge and an exposure to innovative ideas and creativity from all across the globe.

Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri said that the decision to test hiding likes was actually inspired by an episode of ‘Black Mirror’, a television show that explores dystopian scenarios implicating the all-consuming presence of technology as the instigator. The episode in question, ‘Nosedive’, saw a society that was entirely consumed by the concept of likes, so much so that it became a legitimate implication of social class, with characters being denied access to certain places if they didn’t have enough likes, and with their like count literally quantifying their personhood in real time, other people being able to bring their like count down if they had an unpleasant encounter with them.

This led to an incredibly superficial and constrained society where people were at an entire loss for real social interactions because they were so fixated on being agreeable to maintain their social image.

Perhaps then, likes themselves aren’t the problem but instead the fact that many people try to win them by posting superficial content, like the superficial personalities in ‘Nosedive’, and so perhaps the removal could encourage people to post more authentic content, unshackled from the threat of a low amount of likes.

We could all probably do with a detox from the form of social media that has us filtering ourselves to see an influx of usernames fly across our screen, and the ‘like’ has no doubt made us more acutely aware of the way people see us. The pertinence of the validation complex is no surprise to anyone now though, and so it is about time we start becoming more present, realising that comparing our behind-the-scenes to someone’s highlight reel will never make us feel any good.

Featured image: Faye Morton

Find The Croft Magazine inside every copy of Epigram Newspaper.