Amidst ongoing discussions about Bristol's slave-trading past, Epigram examines the reality of modern slavery in Bristol today.

I’m standing outside a grey house in Brentry, Bristol. It’s strangely sunny, with green light flickering down through some winter trees lining the opposite side of the road. The house is nondescript, rundown, lifeless. Semi-detached and small, its dark interior peeks from behind dirty white lace curtains.

Over a period of ten years, over 40 Slovakian immigrants were locked in this house. They were victims of modern slavery: forced to work at a car wash for free, sleeping at night in this house and subjected to violence and death threats. One man who escaped and returned to Slovakia alerted local authorities; the UK’s National Crime Agency launched a surveillance investigation and eventually charged a Bristolian couple for offences related to human trafficking and forced labour.

The investigation tracked down 42 potential victims; 29 gave evidence, including a woman who fled before giving birth to a malnourished child. The true number of victims who were exploited in this house remains uncertain. The couple, Maros Tankos, 46, and Joanna Gomulska, 47, were jailed in June 2022.

Bristol’s history with slavery is well-documented: from its first ventures into the slave trade economy in the early 1690s to its glut of landmarks built by families profiting from slavery, Bristol’s very geography is saturated with indelible reminders of its slaving past.

The vestiges of this trade especially permeate the University’s landscape, from the Wills Memorial Building to Goldney Hall. Ongoing debates around this colonial legacy similarly crackle across the University’s cultural landscape. In this context, raising the issue of modern slavery seems almost anachronistic, or at the very least detached from the cemented realism of Bristol’s historic slavery.

Conceptualisations of modern slavery conjure ideas of geographical distance: sweatshops in India, labourers in Mexico, sex workers in Russia. The locus of modern slavery is delineated to non-western societies: othered, abstract cultures subconsciously viewed as ‘traditional’, ‘inequitable’ and ‘backwards’ in comparison to western liberalism, democracy and fairness.

This is not only a fantastical, reductive binary but a colonial one, and adds to a discourse that mistakenly equates modern slavery with historic slavery. Human trafficking becomes the contemporary equivalent of the transatlantic trade system, a misguided but explicable leap in a city presently wrestling with its overtly slave-soaked history.

The reality is that most human trafficking, unlike the transatlantic trade, is initially voluntary and for judicious rationale. Recent victims of human trafficking could include Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war, or Turkish migrants seeking a new home following the Turkish-Syrian earthquake.

Organisations that coordinate this movement wield enormous power: demanding documentation (passports, identity cards) and inflated fees for ‘safe passage’, vulnerable individuals/groups are left at the whim of their traffickers. This is the cornerstone for potential exploitation.

However, the conflation between historic forced movement and contemporary human trafficking has been subconsciously mainstreamed, producing confusion across conventional western culture. The result is startlingly clear: when I asked students on campus what ‘modern slavery’ meant to them, examples included everything from sex work in Amsterdam to Imperial actions in 19th century India.

‘I think [modern slavery] is mostly corporate: the constant pressure of pleasing your bosses.’ MSc in Nuclear Science and Engineering

‘I can’t define what modern slavery is […] Maybe working at W.H. Smith and they pay you £5.40 an hour? Or people in sweatshops and getting paid minimum wage. Or being used by big corporations; getting coerced into work – like sex work.’ 1st Year, Accounting and Finance

This confusion produces hazy connections between modern racial violations, such as the killing of George Floyd or Tyre Nichols, with disparate human rights abuses such as Andrew Tate’s alleged sex trafficking or county lines operations in the UK.

‘Modern slavery’ is thus something of a cultural misnomer – a misunderstood umbrella term for an ill-defined swamp of exploitative practices. Without an internationally accepted definition of the term, it is both vague and pliable, and therefore ripe for exploitative use itself.

The equation of human trafficking with the colonial slave trade, under the banner of ‘modern slavery’, has enabled anti-migration and anti-immigration policies seem both justifiable and necessary. From Donald Trump’s wall to Brexit’s ‘Take Back Control’, immigrants are viewed with suspicion, and human traffickers painted as immoral; the two together hold parasitic potential, draining western economies, saturating its culture, complicating its nationalism, increasing its crime rates.

Contemporary political rhetoric thus animalises the migrant and dehumanises the discourse surrounding migration, justifying harsh policies. One example includes the UK’s Nationality and Borders Act (2022), which ratified the transportation of clandestine asylum seekers from English holding centres to Rwanda.

All the while, record numbers of illegal migrants continue to cross the channel. Highly vulnerable, those not detected are often funnelled into safe houses and then ‘hidden’ work: dark kitchens, construction, nail bars and factories.

The Slovakian men and women who were transported to Bristol were forced to work in ‘Marios Car Wash’ in Southmead. All their money, including tips, was taken and spent by Tancos and Gomulska in casinos and online gambling sites. Bristol Crown Court calculated that if these people had been paid minimum wage for 8 hours of work a day, then Tancos and Gomulska had benefited from a minimum of £923,835 of free labour.

In this scenario, the nuances of definition seem slightly redundant: clearly an example of criminal exploitation, forced labour and human trafficking, this local case resulted in successful convictions. Yet definition remains important for policy, and the lack of knowledge surrounding what constitutes ‘modern slavery’ influences polarised debates in Parliament, and general apathy on the streets.

‘It all really revolves around capitalism, doesn’t it? But it feels like it’s not really on our doorstep. It’s like migrants in Qatar – that kinda thing where they’re not being paid, safety’s not really a thing […] if they die, like whatever […]; they’re forced to work. That’s modern slavery, I think.’ 2nd Year, Theoretical Physics

A lack of understanding translates to a lack of empathy and subsequently a lack of care. Modern slavery as a term is simply too broad and too uncertain to be helpful on local levels, let alone in national and international spheres.

And so, when notable figures – politicians to actors – decry modern slavery, public outrage is a justified but meaningless reaction. Genuine change requires a more precise understanding of what exploitative practices constitute modern slavery.

Professor Julia O’Connell Davidson, a Professor of Sociology at the University of Bristol, notes that such imprecision is significant: ‘[…] it’s almost unanimously agreed that slavery is wrong. But slavery no longer exists as a legally recognized system or status, so what exactly is [it] that you are calling on [people] to struggle against, and what do you want them to struggle for?’

Julia continues: ‘If you call the exploited car wash or brothel worker a victim of ‘modern slavery’, you deflect attention from the structures that actually created their vulnerability to exploitation.’ Julia explains that if a young homeless person with drug addiction is found being exploited on a construction site in exchange for substandard accommodation ‘he’s not vulnerable because he has slave status. What has left him open to predation […] is the absence of social housing and other forms of social protection, including support services for people with mental health and addiction problems, that has come about […] as a result of years of austerity and assaults on the welfare system.’

🚨 MUST WATCH: Dame Sara Thornton & Karen Bradley debunk the UK Government's rhetoric on Albanians.

— Arise (@arisefdn) February 9, 2023

☀️ Arise hosted a panel in parliament with Dame Sara, Karen, @Andi_Hoxhaj, and @anxhelabruci, which discussed Albania and UK slavery laws https://t.co/VpCCYmYHkW pic.twitter.com/bo3Ud4CTbm

Charities including Unseen UK and Anti-Slavery International similarly cite cuts to the welfare system, including specialist police branches, as critical in the UK’s fight against various exploitative practices. Brexit has also complicated the UK’s relationship with Europol, the EU’s law enforcement agency. This translates to less accountability and less collaboration in what is intrinsically a transnational set of crimes.

Last year's Nationality and Borders Act (2022), proposed by then Home Secretary Priti Patel, promised to curb illegal migration in response to increasing numbers of cross-channel ‘trafficking’. Alongside a swathe of harsher policies towards immigration, this bill detailed a punitive response to modern slavery victims. For example, victims involved in criminal exploitation would be recognised as criminals themselves, invoking longer prison sentences despite acting against their own free will.

Further policies included reducing the amount of time victims have to write their testimonials from 45 to 30 days. For Will Robinson, Senior Fundraiser for Unseen UK, this is ‘very detrimental. Having been through a lot of trauma, you really can’t put a time limit on a witness statement.’

NEW @Freedom_Fund #SlaveryResearchBulletin:

— The Human Trafficking Legal Center (@HTLegalCenter) February 15, 2023

-@BIICL/@UnseenUK study explores how timely, trauma-informed legal advice can improve legal outcomes for trafficking survivors

-@FairtradeUK launches new tool to identify human rights violations in supply chains

>https://t.co/iHaciLEV2s pic.twitter.com/uMxvk9scnt

Aside from this legal antipathy, Robinson cites the government’s lack of engagement as ‘the most harmful thing they could be doing right now’. Strict anti-migration policies appeal to a conservative audience caught in the throes of isolationism, austerity and financial gloom. And looking outwards is easy when channel crossings are at an all-time high.

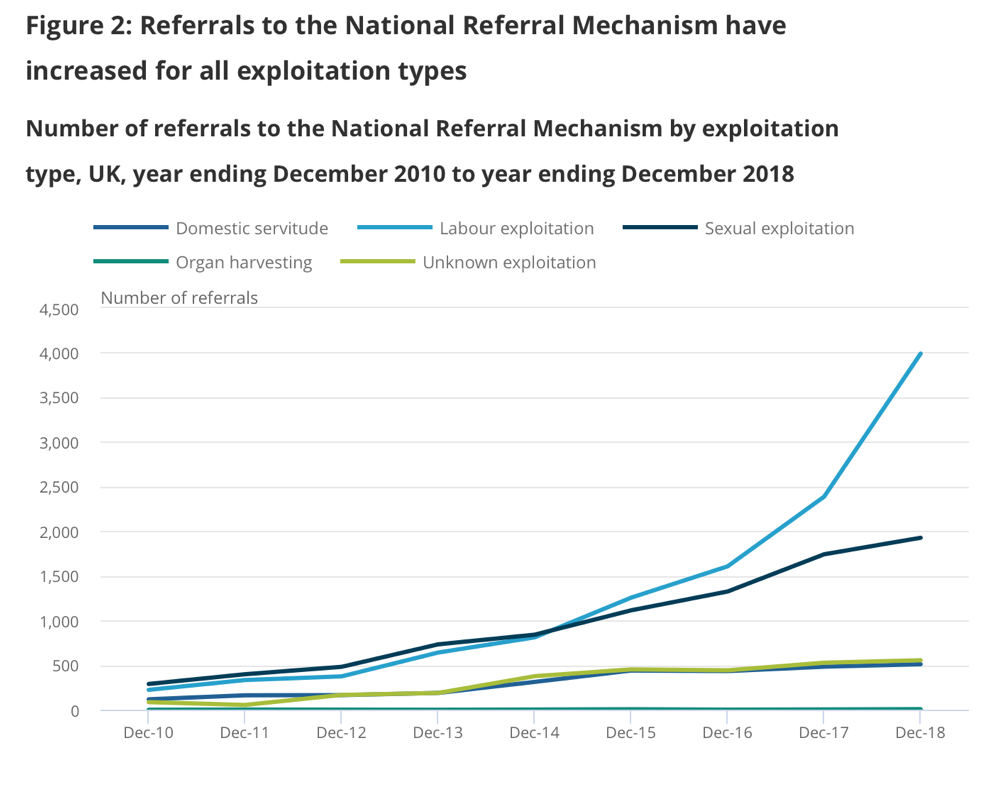

Yet the issue of modern slavery is also somewhat ‘homegrown’: in 2018, according to Office for National Statistics (ONS), nearly a quarter of potential modern slavery victims identified by the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) were UK nationals.[1] Many of these victims are children, with child-related referrals totalling 5468 in the year ending 2022. 79 per cent of this figure were boys, a number which has increased year on year since 2015.[2]

Unseen, whose headquarters are in Bristol’s Hide Market, note that boys are mostly involved in criminal exploitation. Demand for illegal substances, buoyed by the University’s drug culture, creates a profitable market for county lines operations which are often supported by illicit child labour, forced or voluntary.

The developing picture demonstrates increasing numbers of potential modern slaves – both child and adult – in the UK. This trend could be interpreted as promising: higher numbers mean referral systems are working effectively to identify potential victims. Simultaneously, higher numbers could also mean that there are increasing numbers of potential modern slaves in the UK, with an equally increasing proportion of potential victims left unidentified.

As a hidden crime, modern slavery is hard to prevent, detect and prosecute. Many victims suffer emotional abuse alongside physical exploitation, meaning they are often too afraid or ashamed to seek help. The frightening reality is that I could walk past a stranger on Whiteladies Road, or Gloucester Road, or Park Street, and have no idea that they were a victim of modern slavery.

UK charities currently calculate that the UK alone houses between 10,000 and 100,000 modern slaves. This discrepancy is largely thanks to differences in definition: while most definitions encompass 4 main categories – human trafficking, criminal exploitation, sexual exploitation, and forced labour – wider definitions also include everything from organ harvesting to forced marriage.

Differences in data collection and interpretation also contribute to this vast discrepancy. The Police and the ONS rely on a mixture of officially recorded data (for example, prosecutions or referrals to the National Referral Mechanism), and ‘unofficial’ data collected from charities operating safehouses and helplines.

Accordingly, it is difficult to quantify the reality of modern slavery in the UK owing to a lack of definitional and statistical clarity. Prosecution is also difficult: while Tancos and Gomulska were charged in 2017, they were not convicted and jailed until 2022. It took 5 years to collate the evidence of 29 Slovakians who testified against the couple. In that time, all types of modern exploitation have increased, especially labour exploitation.

The future of preventing and detecting instances of modern exploitation is therefore somewhat dependent on greater public engagement. In this instance, Will Robinson believes that a surface-level solution is simple: ‘if something doesn’t feel right, even if you’re unsure, report it to the police or Unseen’s helpline’.

Back at the house, a young woman walks past cradling a baby. The wind picks up and carries the drone of a lawnmower yawning across the estate. This house was once described as ‘a gateway to hell’ but it now just looks like a normal suburban abode, one amongst dozens along this road and hundreds within this community.

My thoughts turn to the 40-plus exploited victims who passed through this house. For 10 years, Tancos and Gomulska kept men and women captive in this property, in a normal Bristol suburb, and no one noticed. This is the reality of modern exploitation: hidden in plain sight, it could happen anywhere, anytime and to anyone. Yet it only takes one speculative phone call to bring the whole system into the light.

Unseen operates the Modern Slavery Helpline: 08000 121 700

1. These records, running to 2020, are the most recent study conducted for adults. A new review is due imminently.

2. For children, there has been an increasing number of cases being reported on the NRM, a trend which can be viewed positively or negatively according to the way COVID’s impact is perceived.