By Charlie Graff, MPhil English

As the government’s new bill to impose minimum service levels on key industries approaches its third hearing, the UCU prepares for industrial action. Epigram speaks to lecturers and interviews students on whether they support the strikes, in order to discover what this bill could mean for higher education.

If passed, the bill would allow the Secretary of State for Business — Grant Shapps — to legislate minimum service level regulations across six sectors, including education. The Trade Unions Congress (TUC) have called the bill ‘wrong, unworkable and almost certainly illegal’; meanwhile the government maintains that the bill is in compliance with international law, and necessary to safeguard the ‘life and livelihood’ of the British public from industrial action in essential services.

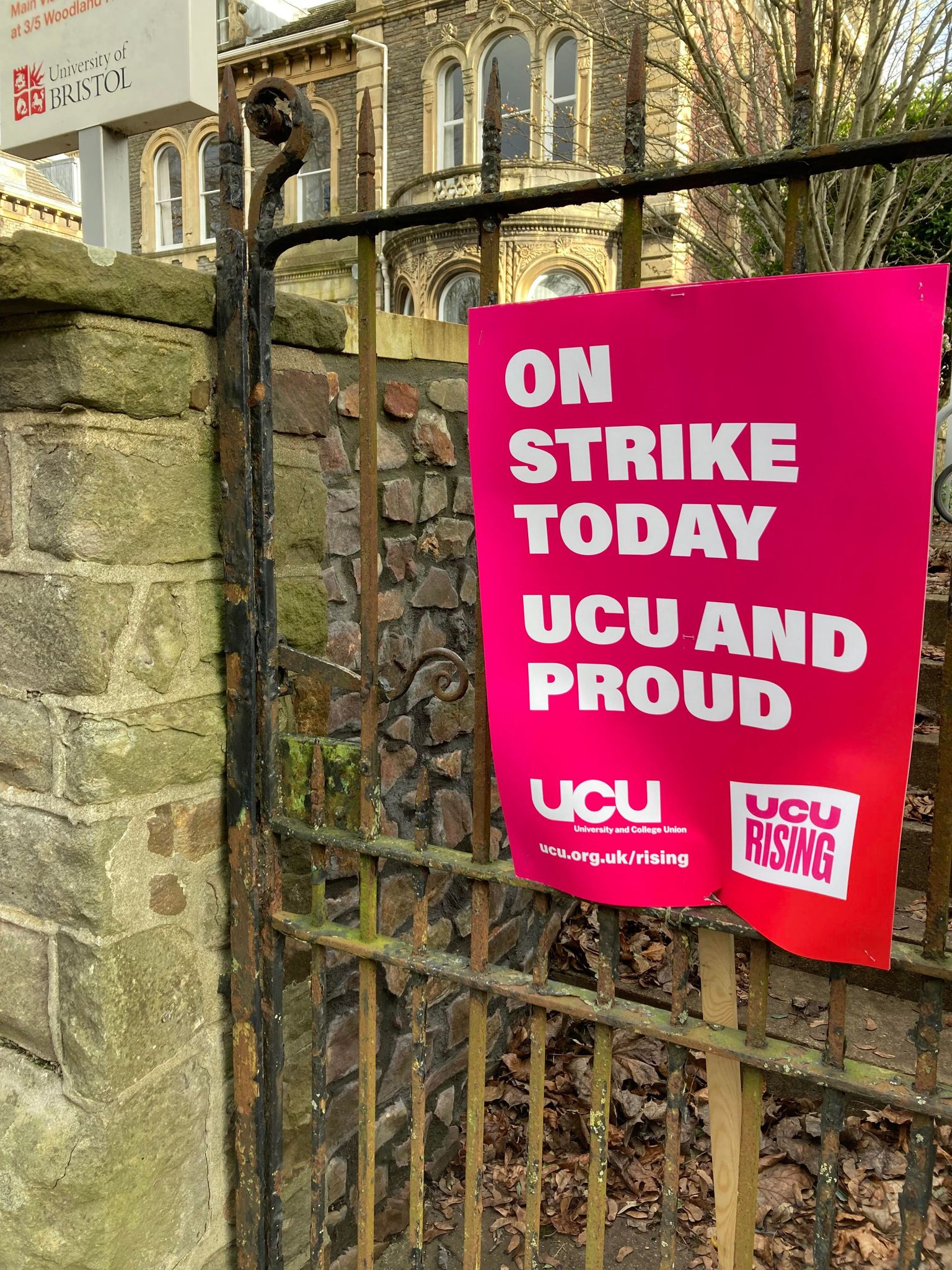

One of the unions facing the possibility of minimum service requirements is the UCU (The University and College Union), which took the first of 18 days of industrial action on the first of February to coincide with the TUC’s national ‘protect the right to strike’ day.

"Huge @ucu march in Bristol to demo assembly point," says our reporter. #Solidarity #strikes #ucuRISING #JustStopOil #1febstrike #SolidarityWithStrikes #NationalShutdown #UCU #ucustrikes pic.twitter.com/FjgOzrwsoR

— Socialist Worker (@socialistworker) February 1, 2023

The UCU is striking for pay restorations, an end to workplace casualisation - which employs staff on short-term rather than permanent contracts - and the reversal of pension cuts, which will see the average lecturer lose 35 per cent of their retirement income. The University of Bristol says that it has ‘made progress’ on casualisation and advocated for increases to staff pay in the universities’ national bargaining arrangement, but was out-voted. Bristol is one of many UK universities that supported the pensions proposal.

Epigram spoke with Dr. Tonia Novitz, Professor of Labour Law at the University and JCNC (Joint Consultive and Negotiation Committee) representative of the UCU’s Bristol branch, to discuss what minimum service levels could mean for teachers and students at the University of Bristol.

Dr. Novitz does not agree with the government’s claim that the bill is in compliance with international law. She says that the bill is not compliant with ILO (The International Labour Organisation) and ECHR (The European Court on Human Rights) definitions of essential services, and contradicts ILO protocol that workers’ organisations must be permitted to participate in defining minimum service levels. She worries that this might harm industrial relations and working conditions.

While the bill has seen considerable pushback from the public due to the effects it could have on the NHS, Dr. Novitz expressed concerns about the visibility of issues facing university staff: ‘I don’t think it has registered with the general public that the majority of academic staff now are on insecure contracts and working across numerous different universities and are earning very little. [...] What is happening to my younger colleagues is just unconscionable.’

Despite the University of Bristol’s claims that it has ‘made progress’ on casualisation and the gender pay gap, Dr. Novitz believes that pathway two (mainly focused on research related activity) and three (mainly focused on teaching and scholarship) staff at the University still ‘tend to be more highly casual, tend to be female and are very unlikely to even begin to get on the payscale to be promoted.’ She sees this as part of a national ‘standard practice’ devised by universities to divide university staff.

Though Dr. Novitz fears the bill’s effect on working conditions and industrial relations could prolong the dispute between the UCU and universities, she hopes a resolution will come soon: ‘People go into academia because they want to support students. Most of us just don’t really want to strike at all, but the quality of the staff’s working conditions also impacts the students.

BREAKING: NOTICE SERVED ON UNIVERSITY EMPLOYERS

— UCU (@ucu) January 24, 2023

18 days of strike action in February and March

1 Feb

9, 10 Feb

14, 15, 16 Feb

21, 22, 23 Feb

27, 28 Feb. 1, 2 March

16, 17 March

20, 21, 22 March

RT if you back our members

UCU and PROUD#ucuRISING pic.twitter.com/WpitQutIYs

‘It seems that acting collectively about this is a way to protect student interests in the long term, and to preserve universities as a genuine place of learning.’

Caught in the middle of the minimum service levels debate are medical students. They face both UCU industrial action and will graduate into an understaffed NHS, which is also experiencing industrial action, with ambulance workers, nurses and junior doctors striking. Epigram sat down to talk with a fourth year medical student to hear their views on the state of the NHS and the impact of the minimum service level bill on the institution.

From their perspective, the government’s deteriorating relationship with the NHS has had a considerable effect on the motivation of medical students: ‘The reasons why people in this country tend to become medical students, myself included, are ones that are very rooted in the ideals of the NHS. To be a medical student is very much to be a student of the NHS.’

Asked about the working conditions medical students are exposed to, they said: ‘I had a day of placement in a psychiatric ward in which I saw a meeting with all of the psychiatric juniors and middle-grade doctors. The overwhelming feedback was people saying ‘I can’t keep doing this, this is unsustainable.’

NHS solidarity with PCS outside Newcastle City Jobcentre. DWP on Strike!#pcsonstrike #feb1strike #BlameTheGovt pic.twitter.com/GpwlojAXse

— PCS Union (@pcs_union) February 1, 2023

‘One of the doctors I was there with spent the whole day on the verge of tears [...] She’d had to send her son to school, despite knowing that he was ill, because there was no senior cover on the ward. She couldn’t have a sick day because, if she did, the ward would then be operating under its minimum level of supervision.’

The student shared the concerns of Dr. Novitz regarding the effects the bill could have on working conditions and industrial relations, saying that ‘If there’s one thing the government has shown with regards to NHS staffing, it’s that they’re not willing to listen to input from healthcare workers and professionals.’

To gauge reaction amongst Bristol’s student population, Epigram spoke to students on campus about whether they support the UCU strikes, and if they were concerned about the impact upon their learning.

Expressing their views on the 18 days of industrial action, one student said: ‘If it’s an inconvenience, that’s the whole point.’

Asked whether they believed the government was justified in proposing minimum service levels in higher education to protect students’ ‘lives and livelihoods’, one student said: ‘No, because my life and livelihood isn’t just the next two or three years that I am studying here. My life and livelihood is the people around me, it’s my professors who would be able to put more effort and be more passionate about their subject. And it’s about me, ten, fifteen years down the line when I’m the one working.’

Another added: ‘I want the university staff to be happy and healthy and able to live on what they make, now and later in life. So this is the complete opposite of what is in students’ and my own interest.’

Multiple students echoed this support for University staff: ‘At the end of the day, you remember a good teacher and you want them to be well off.’

UCU begins day one of strike action

UCU confirms 18 days of strike action to take place in University’s spring term

‘I think that striking is a very important part of any sort of labour force because it ensures equal rights, fair wages, fair working hours.’

Questioned on whether they supported the UCU strikes or felt frustrated by the disruption, one student said: ‘I stand with my teachers, I stand with my professors.’ Another added ‘I’m not frustrated. Pro-strike.’

Of the eleven interviewees, all supported the UCU strikes and none supported the minimum service levels bill.

Featured image: Epigram / James Dowden

Do you support the strikes?