By Kalila Smith, History, Second Year

Reincarnation, animal propagation, a two-child policy, the matriarch, and a couple of condoms. Readers, I present Balloon. Pema Tseden impresses again with a visually aesthetic and eerily candid film.

Set in 1980s pastoral Tibet, a family’s Buddhist faith comes into conflict with government family-planning restrictions. Within the first ten minutes I roll my eyes as Tseden hoodwinks the audience into believing the film will be a male-orientated narrative. But gradually, we follow Drolkar (the mother) more. With three kids already, she faces another pregnancy but is told by the local Lama that her father-in-law will be reincarnated into her unborn child. Unsure of what to do, Dargye (the husband) believes he can force Drolkar’s hand into keeping the child. What a cliché. But with a dual plotline we also engage with Drolkar’s sister, Drolma, who, after leaving a problematic relationship with her nephew’s schoolteacher (Gyal), becomes a nun. Soon after, Gyal writes a novel on the misunderstandings in their relationship, and names it: ‘Balloon’.

In this simple yet thematically complex narrative, Tseden experiments with raw hand-held camera shots and a character-driven plot. The film opening is a blurred camera lens with a soundscape of infant noises. In this immersive environment we realise we are in a child’s perspective. We soon discover that the child, and his brother, were looking through an inflated condom that he has mistaken for a balloon, explaining the myopic beginning. What appears to be a comedically innocent mistake has a snowball effect on the parents; they run out of contraception, resulting in Drolkar becoming pregnant.

Tseden manages to constantly evoke these two diametrically opposed emotions in the audience. He disarms you with brilliantly dry humour, only to then slap you in the face with a socially realist tragedy.

In one agonising scene, Drolkar announces to Dargye that she is pregnant. Nothing. Silence. They hold eye contact for five excruciatingly long seconds as they realise their fate, followed by Dargye walking off. I did not know whether to laugh or curl up in a ball at the beautifully blunt scene.

It was evident that female autonomy could only be achieved by remaining chaste. Yet, ironically, sex is omnipresent in this film. Flashbacks of five-year-old me watching two pigs have sex in a farm resurge, as we have the unfortunate pleasure of watching a ram impregnate many, many ewes.

Whilst slightly traumatising, upon delving deeper, it simply highlighted the similarities on how the family-planning policy and animal breeding treated sex – loveless, bestial, and controlled.

In this modern she-tragedy, the epilogue has a full circle moment as the father purchases two balloons for his two boys. One accidentally bursts and the other drifts off into the sky. In what feels like a Marvel-esque montage, the shots switch between the main characters, in different locations, collectively gazing at the floating balloon – a moment of serenity as these characters catch a brief yet fleeting glimpse of spiritual freedom.

However, the icing on the cake was watching Balloon in the recently reopened Watershed by the Bristol Harbourside: an intimate arthouse cinema that celebrates independent, foreign films that do not conform to the Eurocentric Hollywood industry. This is a must-watch and is certainly promising for the Tibetan New Wave film movement. As an extra bonus, if you watch it at the Watershed you even get given a free condom as you leave!

Featured Image: IMDB

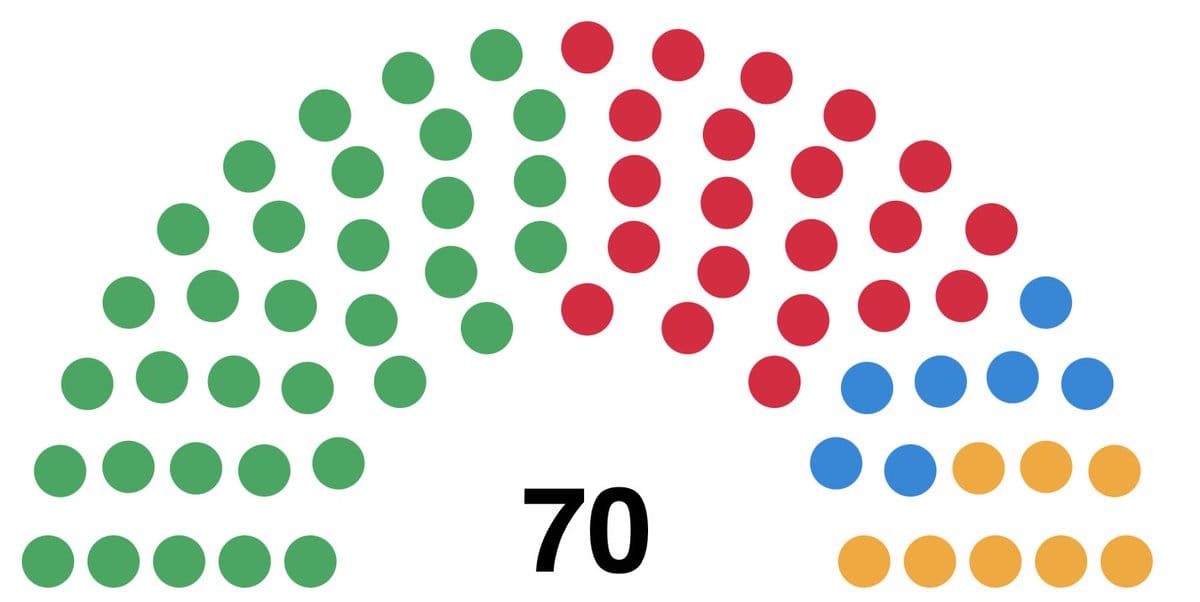

How excited are you to watch foreign films at Watershed again?