By Isha Vibhakar, Theatre & Film, Second Year

As a testament to being “far from the shallow now”, the Academy Awards have rolled out new eligibility reforms for the Best Picture category as part of the Academy Aperture 2025 initiative.

In an attempt to promote diversity and equitable representation, the film academy has established four broad categories addressing gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity and disability: on-screen (A); in key crew members and department heads (B); industry access via internship and training opportunities (C); and in public relations (D). To qualify for Best Picture, films will have to meet two of these four new standards.

“Watch as I dive in” (pun intended) to the subcategories now: for on-screen representation, at least one lead character in the movie must be from “an underrepresented racial or ethnic group”; at least 30% of the general ensemble cast must be from at least two underrepresented groups (women, racial, ethnic, LGBTQ+, people with disabilities); or the movie’s subject must concern one of those groups.

For category B, a film must have either at least two leadership positions or department heads be from underrepresented groups and at least one is from an underrepresented racial or ethnic group; at least six other crew members are from underrepresented racial or ethnic groups, or at least 30% of crew members be from underrepresented groups. For category C and D, opportunities must be extended to below-the-line workers and senior executives from among the underrepresented groups on the film company’s marketing and distribution team.

These new inclusion adjustments were partly inspired by a similar initiative launched by the British Film Institute in 2014, which demanded that films meet certain diversity standards on race and gender inclusion to get BFI funding. Other British organisations including BBC Films, Film4 and BAFTA, later adopted these measures as well.

Needless to say, the above-revised criterion proves how self-defeating the Academy’s efforts at subverting the whole OscarsSoWhite debacle have been. I mean what best way to understand the blurring lines between diversity and tokenism than these “forced diversity” standards. It’s a case of classic Hollywood taking the high road to make the marginalized feel petty. Take the La La Land (2016), Moonlight (2016) mix-up for instance – not only did those who represented La La Land unwittingly steal Moonlight’s moment but also they held up the envelope to reveal the actual winner. Even if you give the presenters the benefit of the doubt, that act unwittingly demonstrates the recurring white saviour trope of Hollywood and makes a well-deserved win feel like a consolation.

When we talk about diversity and inclusion, we mean celebrating our differences. Kathryn Bigelow’s Oscar for The Hurt Locker (2009) has been a site of contention for many. The question remains: did she win the Oscar for the film or her gender because she was competing against auteur and ex-husband James Cameron? Certainly, the war genre is seemingly reserved for men and being the only woman to have won an Oscar for something like that could undermine her win. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran won an Oscar for Little Women (2019), but its director Greta Gerwig was snubbed by the Academy despite the critical acclaim of the film.

What makes me wonder is if these new guidelines will affect any change at all, as films like Parasite (2019) and Slumdog Millionaire (2008) that featured a non-white cast received no acting nominations anyway. According to researcher Daniel Wild of the Institute of Public Affairs, “quotas and identity politics are deeply dehumanizing because they deprive people of being rewarded based on their merit and treats them according to an immutable characteristic” and rightly so!

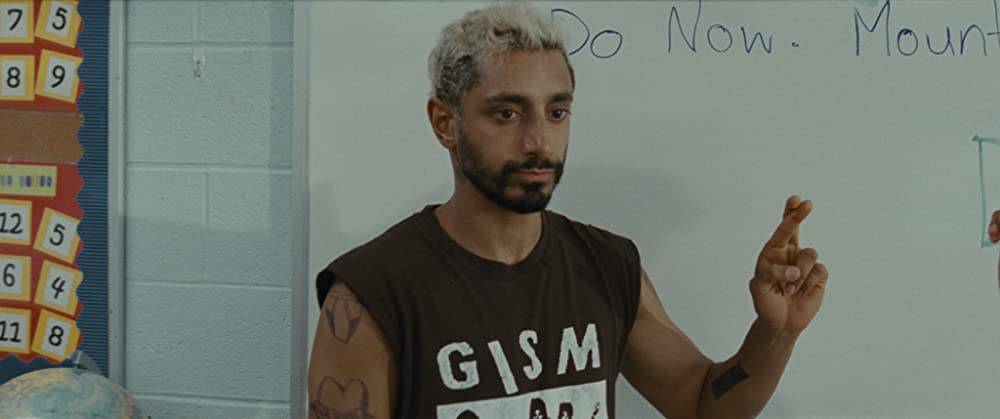

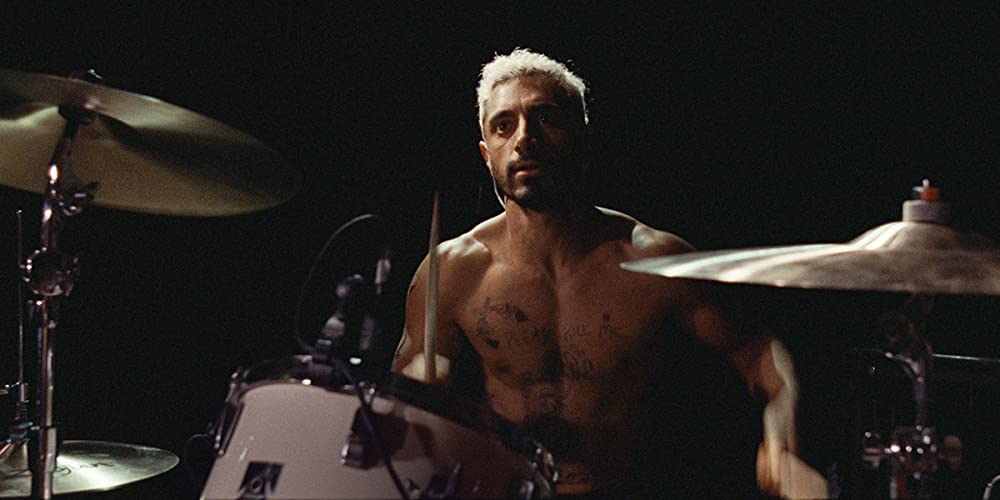

Whilst we still await the result, the nominees at the 93rd Academy Awards include Riz Ahmed for The Sound of Metal (202) and Chadwick Boseman for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020) out of several others, marking a posthumous nomination for Boseman. There has been talk of Ahmed deserving to win Best Actor and how it’s a proud moment for Muslims as he’s the first Muslim actor to even get a nomination.

Countdown to 21 June in film

‘Seaspiracy’ illuminates the dark side of ‘sustainable fishing’

Parasite director Bong Joon Ho mentioned that “the Oscars are not an international film festival. They’re very local” and thus, not an indication of one’s talent. Essentially, Ahmed’s nomination is a small step towards diversity and inclusion compared to all the usual typecasting roles, but this nomination didn’t require any conformity to a specific racial background, so the real question still lingers – do we need these eligibility reforms?

Featured: IMDb / TIFF, gettyimages.com, David Bornfriend

What is your opinion on diversity quotas at the Oscars?