By Sarah Dalton, SciTech Sub-Editor

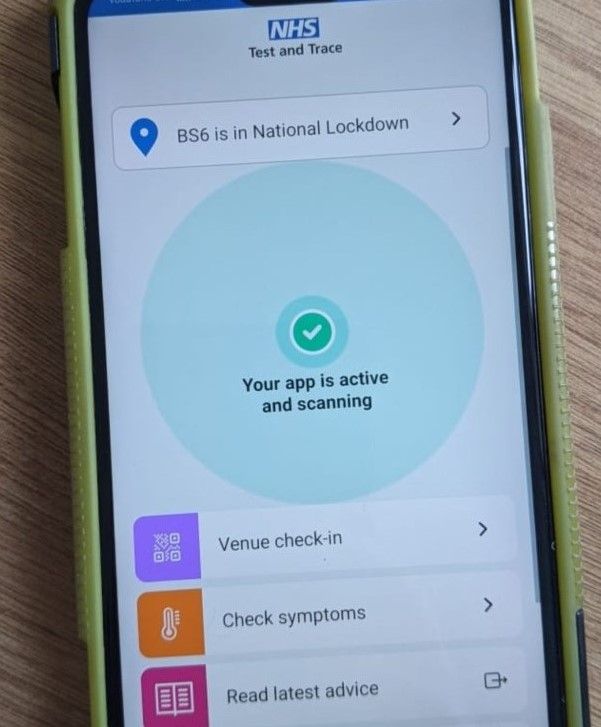

New Bristol research shows the willingness of the UK public to accept COVID-19 data tracking apps - but do our actions speak as loud as our words?

A recent study from the University of Bristol found that more than two thirds of UK participants stated they would support COVID-19 smartphone tracking apps during the months of the first national lockdown.

The majority of these participants also showed support for the introduction of immunity passports. However, these findings do not reflect the number of people who downloaded the NHS Test and Trace app in the study, prompting us to question how far our words translate into action.

There appears to be a significant gap between what people say they’re willing to do and what they actually do

The study, carried out in March and April 2020 by the University’s Cognitive Psychology department, consisted of two online surveys with more than 3500 respondents.

Both surveys presented respondents with two scenarios – an optional app which used smartphone tracking data to identify and contact those who had been exposed to COVID-19, and a compulsory app which enabled the government to locate anyone violating lockdown orders to enforce sanctions.

Both surveys found similar results. Approximately 70 per cent of people accepted the opt-in app which resembled the current NHS Test and Trace application, whilst 65 per cent accepted the stricter version.

When the idea of all data being deleted after two weeks was introduced, acceptance levels rose to more than 75 per cent in both scenarios. This was over 85 per cent when the option to opt-out was available.

Professor Stephan Lewandowsky, lead author and Chair in Cognitive Psychology at the University, noted his surprise by stating that: ‘It’s fascinating how people seem increasingly receptive to their personal data being used to inform themselves and others about what they can and can’t do.’ Yet how do these figures translate into reality?

Remember to download the @NHSuk Track and Trace app >> https://t.co/Kz1t6y6wUd

— Bristol University 🎓 (@BristolUni) October 2, 2020

It will notify you if you're at risk from Coronavirus and you'll be able to alert your friends, family and community📱#StaySafeBristolUni pic.twitter.com/6Em2wgarfF

Whilst the NHS Test and Trace app has become a norm of the COVID-19 pandemic, the application wasn’t introduced to the public until September 2020.

Results from the study suggested that the British public’s receptiveness and therefore the number of downloads should have been high. However, at the end of last month, only 21 million people in the UK had downloaded the app, which is 10 million below the target for it to work successfully.

Potential reasons for this could be technological barriers, lack of awareness, or the nature of the study as a survey, meaning that respondents were likely already interested in the idea and not reflective of the whole population.

However, as Lewandowsky states: ‘There appears to be a significant gap between what people say they’re willing to do and what they actually do.’

The April 2020 survey further explored attitudes towards ‘immunity passports’ (which could be issued to those who have received both doses of the vaccine) and found that only 20 per cent of respondents were strongly opposed to the idea.

Twice weekly Covid-19 testing for students at Bristol Uni extended until March

Looking after yourself following a positive COVID-19 test

However, this recognisable gap between words and actions which the study has already highlighted, suggests that real world use of the immunity passport may be more controversial than it seems at first.

With the UK vaccination programme being quickly spread nationwide, the potential use of the immunity passport is being increasingly discussed, and therefore this University of Bristol study becomes ever more valuable. International follow up research is still ongoing, in order to understand the nations changing privacy attitudes towards technology and law enforcement authorities.

Featured Image: Epigram / Sarah Dalton

Would you be willing to carry an immunity passport?