By Francesca Levi, Third Year, Biological Sciences

Bristol University's Professor Moin Saleem proposes that more than half of the world’s population may already have COVID-19 resistance. This is not due to antibodies, but instead due to T-cells that may have been acquired from pre-COVID-19 coronavirus infections.

Is the end of COVID-19 closer than we think? This is the title of a recent Guardian article featuring the writing of Prof Saleem, who works at the Medical School at the University of Bristol. Prof Saleem states it is likely that in multiple countries where COVID-19 has settled down there is natural immunity to it. In fact, examining current data, he suggests that up to half of the world’s population may already have natural immunity to the virus.

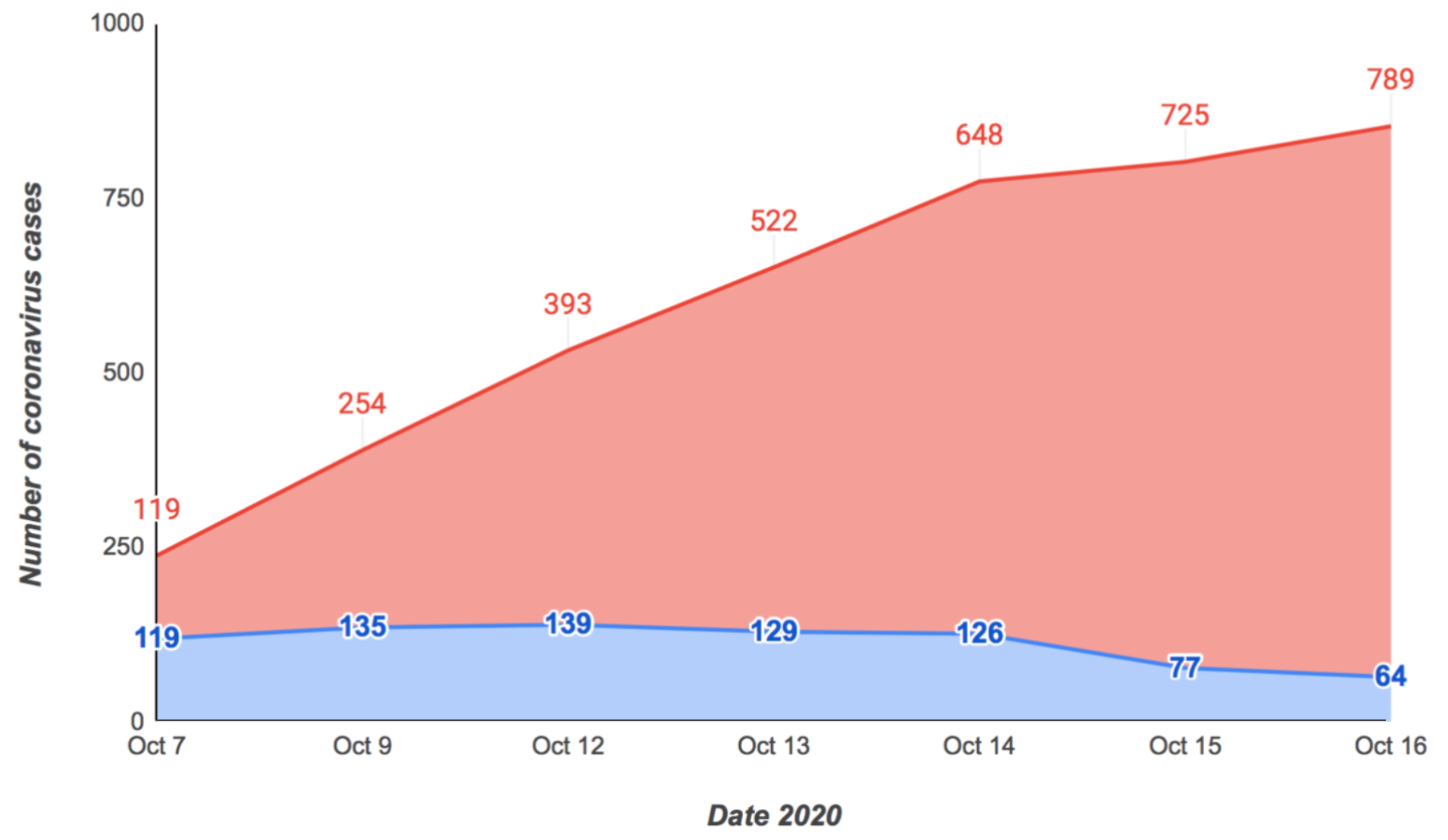

The evidence? None of the studies conducted on Sars-CoV-2 exposure within a closed group showed an infection rate above 50 per cent. Namely, a study by Poletti and colleagues of around 5,500 individuals in Lombardy, who had been in close contact with an infected individual, showed that 51.5 per cent tested positive for antibodies against COVID-19.

But how did such a high rate of resistance arise in populations? A study published in Nature by Julia Braun and colleagues, regarding CD4 T-cells, may answer that. T-cells are long-term immune cells with the purpose of identifying and killing invading pathogens. They do this by binding its surface proteins to the pathogen’s own surface. These T-cell proteins are highly specific when binding to their target, so, when they are exposed to the same pathogen again, they can react fast and effectively.

The study examined the CD4 T-cell infection response to the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 (surface proteins that mark the virus as an invading pathogen), between the blood of COVID-19 patients and healthy individuals. The findings showed that the spike-reactive CD4 T-cells were found in 83 per cent of patients with COVID-19, as expected, but also in 35 per cent of healthy individuals. The T-cells from the healthy individuals resembled those used to fight off two other human endemic viruses from the coronavirus family.

Having T-cells from a previous coronavirus infection may lead to an asymptomatic infection

These findings support Prof Saleem's claims, suggesting that they had been previously created when the patients were infected with these other coronaviruses. Furthermore, another study led by Alba, found that blood samples taken years before the start of the pandemic contained T-cells specific to COVID-19, suggesting a pre-existing degree of resistance within the population.

Therefore, resistance may be conferred by T-cells rather than by antibodies, as was previously believed. Many of the patients who develop antibodies against COVID-19 seem to lose them after only three months. On the other hand, people infected with COVID-19 test positive for T-cells specific to the virus; even when asymptomatic.

Having T-cells from a previous coronavirus infection may lead to an asymptomatic infection. The knowledge that T-cells may confer COVID-19 immunity is massively valuable when designing vaccines against it. The Oxford University vaccine aims to do just that - it successfully triggers the production of T-cells in addition to antibodies.

Why does Covid-19 differ so much from patient to patient? T cells may hold the answer https://t.co/IuoTlLey45 pic.twitter.com/Aytwk4kcL1

— Health24 (@Health24com) October 12, 2020

So where is the catch? Analyses of patients hospitalised with extreme symptoms showed that they had extremely high levels of T-cell activity. Curiously, these cells also seemed to disappear from the blood. No explanation has yet been found for why this happens. Though, the role of T-cells in combating COVID-19 does explain why the elderly are more vulnerable. After individuals surpass the age of 30, the thymus, a gland that is important in the production of T-cells, begins shrinking, thus massively diminishes T-cell production.

Bristol researchers find a potential ‘game changer’ in the fight against COVID-19

Bristol research reveals how cancer puts brakes on the immune system

From evidence provided by the studies, Prof Saleem concludes that about 35-50 per cent of the population is naturally immune to COVID-19. In some regions 25 per cent antibody prevalence is being recorded. We could even be approaching 75 per cent immunity in such regions, which is above the minimum estimated 60 per cent needed for herd immunity. Prof Saleem speculates that in places where death rates have settled to historical norms, there is already natural immunity in play.

He concludes that, ‘we may be closer to the end of this pandemic than we think.’

Featured Image: Epigram / Lucy O'Neill

When do you think life will return to normal?