By Bamidele Madamidola, Arts Critic

From Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade, to the 1960s Bristol Bus Boycott that helped influence the UK’s first Race Relations Act in attempt to outlaw racial discrimination, to the St. Pauls Riot, an uprising against the racial profiling and overall harassment from police under the sus laws, Bristol’s important position in Black British history is unquestionable.

We live and study in a significant city that is vibrant, diverse and full of culture and history. More so than ever, questions about Bristol’s slave legacy and those we deem worthy of memorialising are being brought into question.

Pubs, schools and halls are changing their names and something that has come out of the discussions with people across the country is: who should we commemorate ?

Bristol’s important position in Black British history is unquestionable.

With us in the middle of Black History Month (and, on a personal note, myself longing for new ways to engage my brain when locked indoors), I asked students across the campus about their own Black role models and favourite cultural icons.

Admittedly, it seems I knew little more than the typical American Black figures, such as Rosa Parks, that I was taught in primary school.

Ojinika Agbu, English, Second Year, President of AfroLit Society:

This Black History Month feels different. It feels like now more than ever we need to highlight and put at the forefront, stories of black success and joy and the many times that Black people have beaten the odds and paved the way for not just theirs, but everyone’s liberties.

For my Black historical figure I wanted to stay close to home and shed a light on Bristol’s own Marti Burgess (the Black woman you should probably be thanking if you’ve ever had a wild night out at Lakota)

Marti Burgess...the Black woman you should probably be thanking if you’ve ever had a wild night out at Lakota

Marti bought and ran the popular club with her brother Bentley and made it the first to tour post-Apartheid South Africa, hosting some of the country’s first integrated discos.

She also became the first Black member of Bristol’s Society of Merchant Ventures (infamously once led by Colston himself), tackling Bristol’s systematic inequalities and rewriting the legacy.

LABI SIFFRE - MY SONG

— Labi Siffre (@labisiffre) August 31, 2020

This comprehensive 9CD set contains all of @labisiffre's albums: 146 tracks including 44 bonus tracks, the “Happy” album reissued for the 1st time & in-depth liner notes based on hours of Q & A's with #LabiSiffre himself.

Order now:https://t.co/Vv7km7MweH pic.twitter.com/MUqkuW4gfk

Another figure I would like to highlight who also feels close to home, is British-Nigerian musician, poet and playwright Labi Siffre. You’ve probably heard him sampled on your favourite rapper’s record, from Kanye West to Jay-Z to Eminem.

But being a Black, gay singer in the seventies who was open and honest about his sexuality meant he never really managed to make it that big. One of his defining tunes, ‘My Song’, is an example of how he used his music as a form of revolution.

The song encapsulates the passion and pain of a person trying to make their way in a world that refuses to provide them a path. This Black History Month, he teaches me to keep using my art, in any way I can, to make a change.

Danique Bailey, English, Second Year, founder of 100 Black Voices:

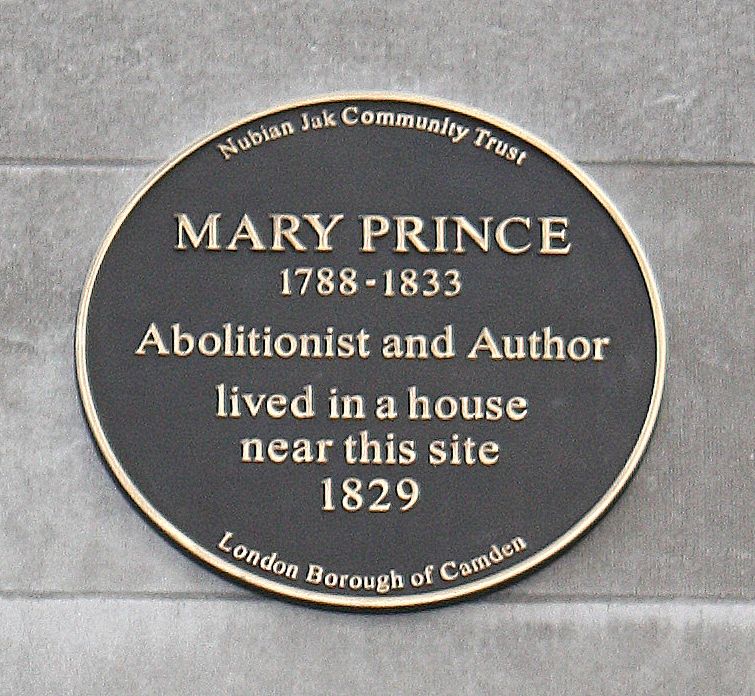

Mary Prince was one of the first Black writers to be published in Britain and wrote her autobiography The History of Mary Prince in 1831, after escaping slavery in Bermuda.

Prince’s autobiography highlighted the horrific life stories of enslaved women and men, which helped to change public opinion on slavery, which was still legal in Bermuda and the West Indies.

Writing has been used throughout history to shed light on important issues, with some of my favourite Black writers being Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou and Grace Nichols.

I think first-hand accounts like these are so important because literacy was a sense of freedom: slaves were not allowed to read or write.

Writing has been used throughout history to shed light on important issues, with some of my favourite Black writers being Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Malorie Blackman, Benjamin Zephaniah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Grace Nichols.

Poetry is significant, both for fun and for serious purposes, in ways that do not directly relate to the arts.

For example, Muhammad Ali recited a poem from memory during an interview in Ireland, to commemorate the prisoners killed during the 1971 Attica prison massacre.

He also used his poetry to build his persona, which helped encourage people to buy tickets and watch his fights. He is remembered as one of the greatest boxers of all time.

Morayo Omogbenigun, Social Policy, Second Year, Afrocentrik Director and LGBT Rep of ACS and Treasurer of AfroLit:

Growing up in Nigeria, you’re always made aware of the cultural icon, Fela Kuti. Both an activist and a musician, he is truly a national treasure – even though the government attempted to arrest him over 200 times.

Something less talked about is his band, and the fantastic musicians that provided the driving beat to classics like ‘Zombie’ and ‘Water’.

My cultural icon is actually Tony Allen, who was Fela’s drummer. When listening to Allen’s solo work, I hear a lot of drum patterns that remind me of modern day house music – my favourite one of his tracks is ‘Afrobeat Jam’; it could easily be a track on a KAYTRANADA album.

To me, Allen is a cultural icon because not only was he a pioneer of West African highlife music, he helped take it to the world, collaborating with international artists such as Damon Albarn (frontman of 90s Brit-pop band Blur) and paving the way for so many young, Nigerian talents like Burna Boy, Wizkid and Rema.

Even though he’s passed, his beats are still influential today, and even featured alongside Skepta on the Gorillaz song ‘How Far?’ earlier this year.

After these interviews, I started to do my own research on Black cultural figures and found Dolores Campbell.

For 18 years, Dolores was a foster carer to more than 30 children. She was the first female member of the Commonwealth Coordinated Committee (CCC) set up to focus on open racial discrimination in Bristol in the 1960s and was one of the founders of St Paul’s Carnival celebrated every year on the first Saturday of July.

Black History Month at the University of Bristol

Editors’ Picks: Black History Month

Her mural lies emblazoned on a wall on Campbell Street, St. Pauls, with her smiling down, exuberant with Black joy, surrounded by red lilies and a drawing of the sun shining down on a group of children.

It is a part of Easton-born artist Michele Curtis’ ‘Seven Saints of St. Pauls’, which celebrates Black Bristolians.

When walking down St. Pauls toward Easton to visit the barbers, I now think about that drawing on the mural and Dolores Campbell. I see a vibrant and inclusive history depicted on the walls, reflecting its diverse population; because Bristol’s Black history is inextricable from British History.

You can find out more about Bristol’s black historical figures:

Bristol Museums collection about Black History

Bristol Museums piece about ‘Seven Saints of St. Pauls’

And watch out for Bristol SU BME Network events for Black History Month

Featured Image: Paintsmiths / Michele Curtis

Who are your Black cultural icons?