By Bamidele Madamidola, Arts Critic

Next year, GCSE students in England will be able to drop topics in subjects such as English Literature, meaning, for the first time, poetry will become optional. To some, the idea of not studying the supposedly elitist art form sounds like heaven. But as the pandemic has shown us, poetry can be a valuable form of connection and stir a growth in our humanity.

The year is 2017. June 2017 to be exact. You’re in your last GCSE English Literature exam. Modern texts and poetry. At 2 hours 15 minutes it’s your longest paper. You look around the hall and see your friends signing the cross. You decide to do the same: a small prayer, hoping that anything comes up but Imtiaz Dharker’s ‘Tissue’. The invigilator says ‘you can begin’. You turn the page and see ‘Bayonet Charge’. Thank God! Hallelujah!

I was a part of the guinea pigs for the GCSE reforms in English and Maths with the grading system changing from A*-G to 9-1. The teachers were stressed about teaching new texts for a closed-book exam and unsure what a Grade 9 student piece of work looked like. To achieve this top grade in Literature, AQA students had to study a Shakespeare play, a 19th century novel, a modern text of either prose or drama, an anthology and be equipped for unseen poetry. All these components were examined with an ‘insightful analysis of language, form and structure’ in a ‘convincing and conceptualised’ response expected on the day.

my sister will never know the fleeting anxiety just before gcse english literature paper 2 at the possibility of getting singh song for the poetry question 😤

— sami (@saaaamiiiiiiii) August 5, 2020

Recently, the Department for Education has decided for a ‘choice of topics on which students will be examined’ for the 2021 GCSE exams with English Literature being one of the subjects wherein aspects of the course become optional. Shakespeare will remain compulsory but teachers will have to choose two out of the three other components (19th century novel, a modern text, or poetry). Kate Clanchy, a Scottish poet and writer, expresses concerns that for the first time ‘poetry is an option’, rather than a central pillar of a literary education.

Admittedly, even as a first year English student, I can say I do not read a lot of poetry for pleasure. At GCSE I preferred my Priestley and Shakespeare to my Browning and Duffy, but poetry was an important component of the course.

What the next GCSE students will be missing, besides the top-notch literary memes and learning the catchy songs by Mr. Bruff, is a deeper understanding of the world through poetry.

Poetry is, in fact, a popular literary undertaking that the next GCSE students will sorely miss. Clancy has cited in the article a survey by the Children’s Literacy Trust, which recorded that 48% of youngsters regularly engage with poetry, thereby highlighting not just its importance, but its popularity.

Poetry becoming optional implies a disposability to the humanities

My Power and Conflict anthology covered topics such as loss, the past, identity, pride, and nature. For a Londoner, it made me want to experience the ‘fear, awe and wonder’ Wordsworth felt in the Lake District; I learnt about the Crimean War through the eyes of Tennyson’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ and became more conscious of our growing apathy and desensitisation of wars in Duffy’s ‘War Photographer’.

The idea of poetry becoming optional implies a disposability to the humanities.

Although the poetry component was difficult, with one of the 15 poems turning up and having to be compared with another on the day, some argue that these exams are character-building. But more importantly, it is one of the few places in the course that marginalised voices are heard outside the echo chamber of past, white men.

Others argue that it will help reduce the stress students will face next year on top of exams and going through a pandemic; others even suggest Literature should be made non-mandatory as a whole, and the focus should be solely on English Language.

Instead of removing poetry from English literature courses they should just make English literature a non-mandatory part of the curriculum. Make English language the GCSE that everyone takes, and have literature be its own course for enthusiasts

— Waldorf Sixpence (@WaldorfSixpence) August 5, 2020

But a literary education (including poetry) helps create a well-rounded human being. Arguably, poetry is as important as learning about eutrophication in biology or learning about hydrocarbons, completing the square and more. It helps develop knowledge and skills needed in the future.

In the midst of a pandemic, poetry has provided many with solace. From people isolating themselves with family to people living alone, poetry has become a means of reflection as we’ve become forced to pause from our busy lives. For those experiencing loneliness, poetry has provided a means to connect with others: not merely with past poetic voices, but also through sharing poems with loved ones and boosting morale online.

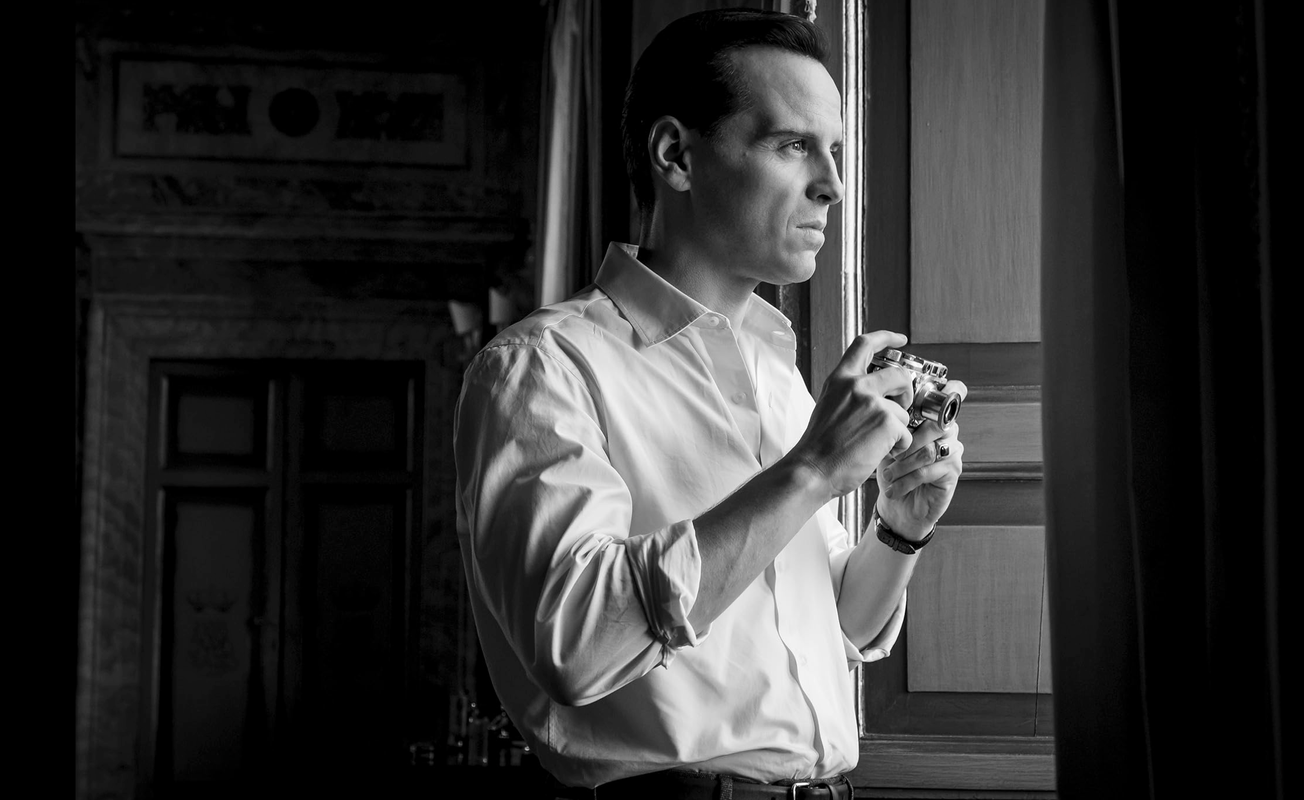

One of the many ways poetry is being shared is through Instagram. Celebrities such as Andrew Scott and Helena Bonham Carter have been reciting poems to help people cope with our current situation.

In the midst of a pandemic, poetry has provided many with solace

Andrew Scott recites a reassuring poem about hope and resilience by Irish poet Derek Mahon, encouraging us to see how ‘Everything is Going to Be All Right.’

I may not need to work out how to use a quadratic formula again, but GCSE Maths will likely help someone on their journey to becoming an engineer. And whilst I may have found it pointless, and incredibly difficult at the time, in retrospect, mathematics has helped me interpret graphs, draw conclusions and much more.

GCSE poetry provides a foundation for those who take A Level Literature. And for those who, like me, devote three years of their life to the study of words, A Level Literature is a prerequisite for many Universities.

Come Results Day 2017, a handful of us achieved this enigmatic, supposedly rare, top grade in Literature. During A Level I studied and adored Christina Rossetti.

Reading Rossetti, I learnt how to handle loss, how to deal with unrequited love and the importance of being selfless, whilst learning about the plight of being a 19th century woman through her unmistakable critiques of the times in which she lived, which are sadly all too relevant today.

But most importantly, Rossetti has taught me to never take fruit from goblin men.

Reading Rossetti taught me how to handle loss, deal with unrequited love and the importance of being selfless

My relationship with poetry has been a tumultuous one, with moments of stress-induced tears when memorising quotes. Ultimately, however, I’m glad I learnt it and believe I’ve grown as a result.

In the words of T.S Eliot: ‘[With poetry] there is always the communication of some new experience, or some fresh understanding of the familiar, or the expression of something we have experienced but have no words for, which enlarges our consciousness or refines our sensibility’.

I hope the youngsters get to experience Eliot’s view here, just as I did, and aren’t made to have this an option.

Featured: Unsplash

Are you saddened to see poetry be made optional?