Hannah Green takes a trip through the history of psychoactive substance use as a motivation for producing art, music and literature.

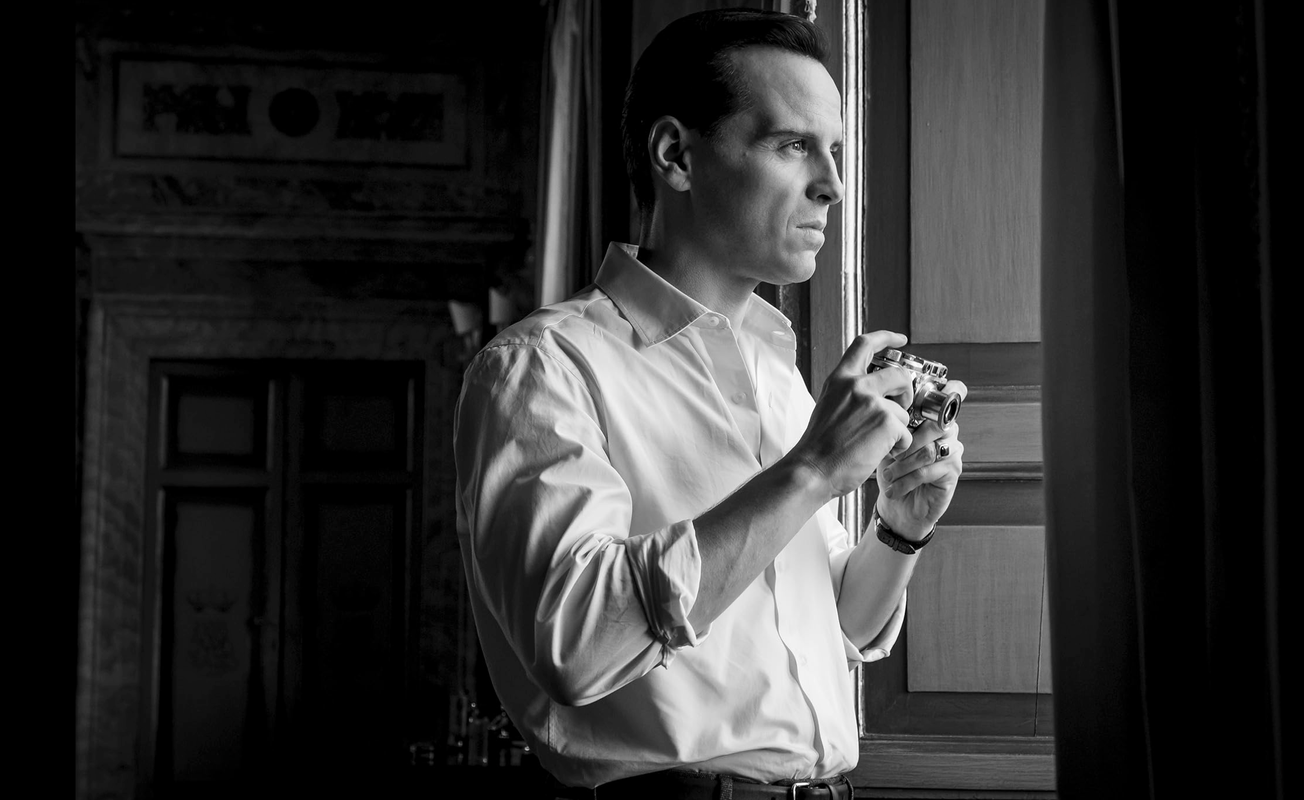

On the 19th of April 1943, Dr Albert Hoffman took LSD internally for the first time. On his bike ride home from work, he first experienced the effects of the psychedelic substance, sparking a whole new wave of possibilities and controversies surrounding the use of the drug. In light of this year’s Bicycle Day, as it has come to be known, Epigram looks back on the effects that this discovery has had on artists and creators of all kinds over the intervening decades.

psychedelic art is either very much a social product of its time, to be considered within its context, or as a genre only ‘understood’ by those who like to experiment with hallucinogens themselves.

Think psychedelic art and what might immediately spring to mind is the trippy artwork and New Age sounds associated with the West Coast music scene of the 1960s. However, there’s much more to this stereotyped and much misunderstood genre than meets the eye, and there’s barely a medium that has remained untouched by the revolutionary and subversive use of psychedelic substances. The impact of drugs on art goes back millennia, but combining radical, illicit substances and art’s power to speak to and for the masses has led to a cocktail of expression, repression and debate in the past 60 years.

Happy Bicycle Day! How a Swiss chemist accidentally gave himself the world’s first acid trip on April 19: https://t.co/zTteruOzNx pic.twitter.com/WRihOSlvUz

— Slate (@Slate) 19 April 2018

The term ‘psychedelic’ was first coined by doctors in 1956 to describe hallucinatory experiences, but it was the use of drugs by bands such as Jefferson Airplane, The Grateful Dead and The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and their tangible presence in the music, artwork and live show production that really brought the concept to a wider public. These pioneers of psych-rock included heavily suggestive lyrics (in the case of ‘White Rabbit’ by Jefferson Airplane), and album art featuring bright colours and distorted patterns and lettering, now stereotypes of the genre (Think the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Pink Floyd, The Byrds).

There was very much the idea that music and visuals should go hand in hand, with multi-sensory immersive experiences created at gigs and concerts through the use of coloured light displays, lulling the audience into an magical, trance-like state inextricably connected to the music.

The ‘discovery’ of LSD and other psychedelics influenced many others outside of the music industry, bound up as it was within the radical counterculture movement that developed in Britain and America throughout the 1960s and 70s. In many people’s minds this is where it ends - psychedelic art is either very much a social product of its time, to be considered within its context, or as a genre only ‘understood’ by those who like to experiment with hallucinogens themselves.

However, psychedelic art can be seen as much more than a simple reaction of the discontented youth searching for something higher and purer during the Summer of Love- in fact, its influence changed the direction of popular culture and created the creative landscape we see today. For example, LSD has been cited as a major part of the Beatles’ change in artistic direction around this period, as well as that of Bob Dylan.

Does one need to be on drugs to experience [psychadelic art]? Or even to create?

Consider the music world without albums such as Revolver (1966), and literature without Burroughs and Ginsberg. A life on the margins of society and heavy drug use were deeply embedded aspects of the Beat generation’s lifestyle in the 50’s and 60s that fed into these later counter-culture movements of later decades.

Drugs such as marijuana, benedine and LSD were used with abandon and in some senses glorified in the works of writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and, most pertinently for this article, William Burroughs. While Junkie (1953) delved into the experience of heroin addiction (something Burroughs himself was familiar with), Naked Lunch (1959) moved into a non-linear style that was intended to be as immersive, bizarre and nonsensical as an extended trip.

Isaac Abrams is a great example of a pioneer of psychedelic art, having been very open in interviews, and indeed on his website, about the extent to which drug use influenced his art. His strange, intricate patterns seems to move on their own, whilst striking colours pull the viewer in. They are beautiful and otherworldly, whether or not you’ve ever had a hallucinogenic trip.Returning to the question touched upon before - as a part of the counterculture, psychedelic art is seen by many as peculiarly in and of its time. Does one need to be on drugs to experience it? Or even to create? Attempting to paint on acid has been described as trying to paint whilst falling down a flight of stairs, and many artists have indicated that rather than drawing directly from the visuals, they are inspired by changes of perceptions of reality afforded by the experience. Alex Grey is an artist still creating psychedelic art for our times. His art is intended to be enjoyed whilst tripping, which, while opening up new avenues for exploring art, also closes off the full experience for those not willing to take drugs.

Psychedelic art has never really been accepted as highbrow ‘art’ in the truest sense- perhaps because of its relation to music scene, the cultural moment that it defined, and of course the illegality of its influences, and the resulting unwillingness of galleries and dealers to endorse it.

To many perhaps these works seem unsetting, if not inaccessible. However, the beauty of psychedelic art, from paintings to poetry, is not that it makes sense, that it is there to be interpreted and understood - rather, it captures a mood, a perception, an experience, a musical movement and a time of cultural change.

How do you feel about psychadelic art? Let us know in the comments below or on social media