By Isabel Bromfield, Second year, Mathematics

As the proclaimed ‘year of climate action’ begins, can the UK achieve the progress it needs to make in order to have a sustainable transport system by 2035?

In a recent press conference at COP26 climate summit launch, Boris Johnson stated that all cars sold in the UK will be electric or hydrogen-powered by 2035; a 5-year push forward from the government’s original ‘ban’ on fossil-fuel powered cars by 2040.

Doubts have been cast on the feasibility of this claim: while Johnson would like to paint the UK as the frontrunner in climate policy, the real picture is much less certain. Banning the sale of petrol cars is a large part of the UK’s aim to become carbon neutral by 2050, but its direct effects on consumers makes creating a carbon-neutral transport network a significant challenge.

One of the biggest challenges is encouraging the public to purchase electric vehicles. Without a significant customer investment into sustainable vehicles, improving the system will be much more difficult. While the government plans to implement a ban on the sale of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars by 2035, incentives exist for consumers to make the switch before then.

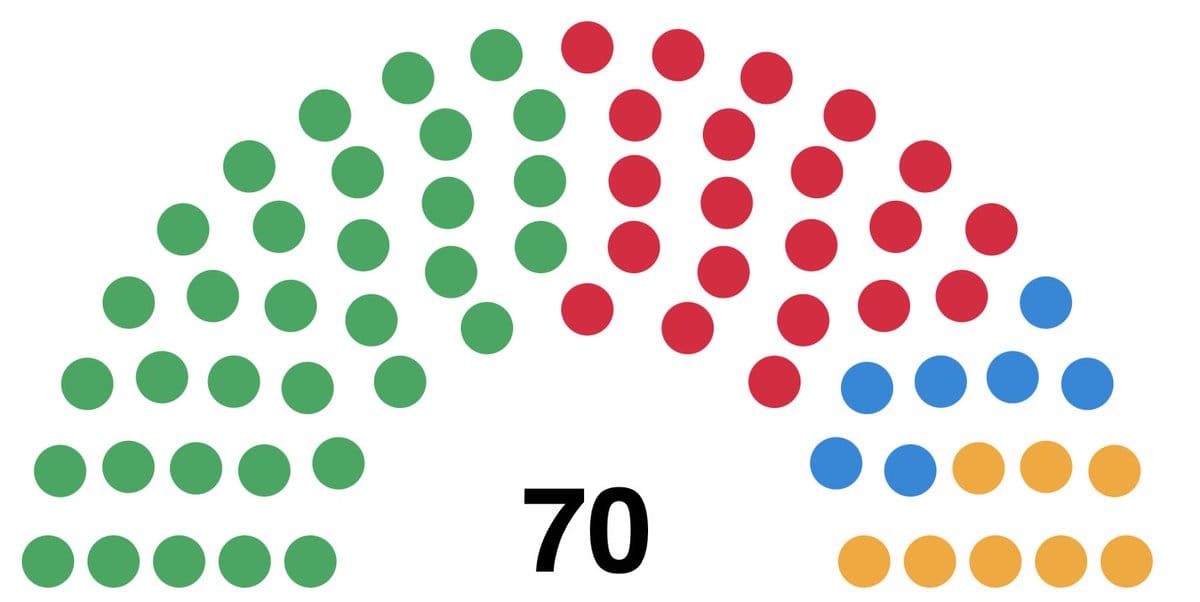

1.28 million electrified vehicles were registered in Europe in 2019 https://t.co/A52hMxkNnb pic.twitter.com/Z0LAjmWuT9

— Electric Cars Report (@ECarsReport) February 19, 2020

The ‘Plug-In Car Grant’ has been lowering the price of new electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles by up to £3,500 since 2011, and has contributed to the purchase of more than 160,000 cars since its introduction. Several grants also exist to subsidise the cost of private vehicle chargers. However, with the withdrawal of funding for hybrid cars in 2018, and the current subsidy for electric vehicles expiring in March, it is expected that the grants will cease altogether in the coming months.

While innovations in energy storage and consumption will dramatically decrease the price of electric cars in the next few years, the average price of a long-range vehicle starting at £22,000 is for now undesirable to most consumers. On the other hand, electric cars are significantly cheaper to run than both hydrogen cell and petrol cars, averaging about 3.3p per mile instead of the typical 10.9p of a petrol car. Depending on expected mileage, electric could still prove a better investment today.

However, the largest challenge for the future is creating sufficient infrastructure to support an influx of sustainable vehicles; something the government is apparently struggling to do. Critics claim that there is not enough investment in infrastructure for sustainable vehicles to help consumers make the switch.

Though hydrogen fuel cells have been touted for years as the future of travel, there are only four filling stations north of London. The government instead seems to be focusing on electric vehicles, given the ease of installing charging points compared with transporting hydrogen around the country. However, reports have stated that at least 4,000 electric charging points should be installed per day in order to reach the 25 million that would sufficiently power all the UK’s cars.

Currently there are 30,000 public points. While the government has encouraged councils around the UK to make use of a £4.5 million grant for installing charging points in public locations, the majority remains unused, with only five councils taking advantage of the funding as of 2018.

Another challenge consumers face is charging times; slower charging points can take up 11 hours for a full charge. For longer journeys and homes without a charger, this is a barrier to buying electric vehicles. Thankfully, ‘Rapid’ chargers which can fill a battery in under an hour have been steadily growing in number, though there are currently only 2,000 locations in the UK. Sufficient innovation and investment in this area could make the inconvenience of charging a much lesser one.

As part of their Decarbonisation plan, the energy market regulator Ofgem recommends the use of smart chargers. In a country that will be growing evermore reliant on electricity as conventional boilers are replaced with heat pumps and batteries replace petrol, efficient use of electricity will be paramount.

Smart chargers allow the user to restrict the power delivered to the car or halt it altogether at times of high energy demand, saving consumers and energy networks money. They also could possibly be used for “short-term storage to smooth peaks in energy demand and maximise use of renewables”, saving the UK an estimated £2bn. In all likelihood, the government will accept the recommendation, which could ease the pressure on the country’s energy suppliers in the transition to electric vehicles.

| Flying cars could bring sci-fi to our cities

The environmental benefits of electrical and hydrogen-fuelled cars are numerous: as well as reducing the impact of the UK on fossil-fuel emissions around the world, clean vehicles will mitigate air pollution in cities. Bristol’s poor air quality contributes to five deaths a week, according to a study by King’s College London.

Though the production of batteries for electric cars makes their production more polluting than petrol cars, this is more than made up for by the lack of emissions over their lifetime. At the current rate, creating carbon-neutral roads by 2050 is unrealistic. While the government declares 2020 a ‘year of climate action’, policy must match up in order for them to fulfil their own promises.

Featured image: Epigram / Vilhelmiina Haavisto

Will the UK go electric by 2035? Let us know your thoughts!