By William Sinclair-Man, First Year, Film and Television

The first in Kieslowski’s thematic Three Colours trilogy -which focuses on the different aspects of the French motto “Liberté, égalité, fraternité”. Three Colours: Blue (1993) depicts a woman’s attempt to liberate herself from grief after the death of her husband and child.

Blue is the colour of fresh bruises: The body's reaction to trauma and its attempt to heal itself.

Initially, Julie (Juliette Binoche) refuses to heal; she hides from her past, abandons her home and possessions (save for her daughter’s blue mobile) and destroys her late husband's unfinished symphony. Through her daughter’s room and mobile, the ink on the music sheet and uneaten lollipops, blueness becomes entangled with Julie’s past, a symbol of everything she’s lost.

The film understands the visceral emotionality of colour. It transcends realism, instead using colour in an impressionistic and allegorical way. Blue haunts Julie not just in past mementoes but through the world itself. At times it floods through the windows covering everything, drowning her in it.

Other colours appear prominently as well, yellows and green, suggesting there is more than just grief out there for Julie to find. Overall, the use of colour contributes to a dreamlike and emotionally heightened atmosphere by surpassing pure representation in favour of a uniquely cinematic presentation.

Like colour, music too conveys the same sense of immediate emotion as the film. The film’s score, composed by Zbigniew Preisner, serves a vital role in the film’s construction. Not only does it heighten the emotion of each scene in which it appears, but it also serves a secondary narrative purpose.

Though at first, the music seems to come from outside the world of the film, the main character shows an awareness of it. It’s as if the music is part of her thoughts, a taunting memory. The unfinished symphony serves as a mirror to Julie herself in its destruction and later reclamation; Julie runs her fingers across the paper, and the notes begin to play; as it’s destroyed, the sound becomes warped.

Like the main character, the symphony is constantly evolving throughout the film.

The film's relationship with colour and music is exemplified best in the composition scene towards the end of the film, in which the frame blurs, completely abstracting everything into pure colour while her husband’s symphony plays, changing as the characters discuss it.

At this moment, the film abandons any notion of capturing reality as it appears, opting instead for storytelling through pure colour and music.

However, it’s unfair to reduce the film to just an intellectual exercise: a series of motifs, allegories, and themes; it’s also a profoundly humane and moving film. Its inhabitants feel real and complex, as in life, they remain unknowable to a degree.

The script and performances (particularly Binoche’s lead performance for which she won the César Award for best actress) lend them an implied sense of depth, as though their lives continue outside the screen’s borders.

Overall, Three Colours: Blue is an inventive and uniquely cinematic film, both thought-provoking and emotional in equal measure. It shows that though the grief never fully disappears, blue is not just bruises; it’s also the sky beyond the clouds. That the world is full of colour, waiting to be seen.

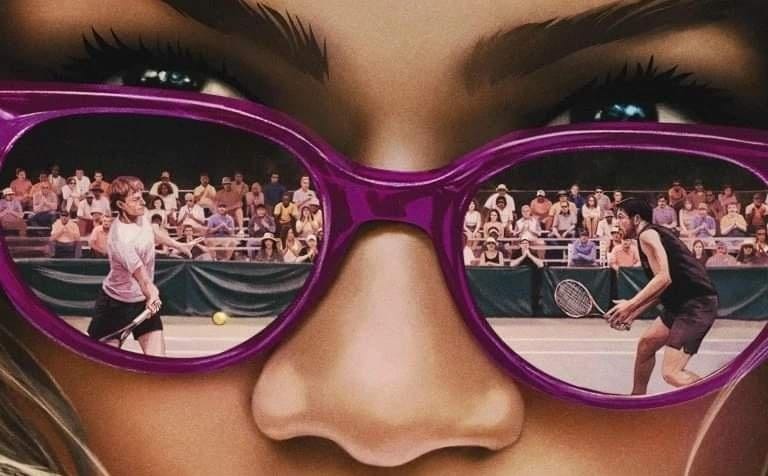

Featured Image: IMDB

Have you watched the first instalment of Kieslowski's Three Colours Trilogy?