By Gaby Turner, Comparative Literatures and Cultures MA

Whether you love to hate or hate to love Sally Rooney, it's undeniable that she’s been turning heads in recent years. Her novels float seamlessly between YA romance and modern classic, drawing in fans across geographies, generations, and genders.

For months, my Instagram explore page has been flooded with people boasting their review copies of her latest novel Intermezzo, and the fated release day at the end of September saw bookshops in London and Dublin opening their doors at 8am to satisfy the crowds itching to get their hands on a copy.

Rooney’s had her fair share of complaints; readers have voiced their frustration over the lack of speech marks and the miscommunication trope. In September 2023, one scathing New Statesman article infamously lumped ‘any novel by Sally Rooney’ in with what it termed cool girl fiction. The article’s author, Charlotte Stroud, bemoans the uniformity of this ‘monstrous genre’ which centres around the ‘depressed and alienated woman.’

But the complaint that has sparked the most controversy recently is simply that Rooney's protagonists are all thin.

In September, an article in Vogue by writer Emma Specter called out the novelist for her intense focus on the thin body. This sparked a frenzy of articles, quick to cancel each other and to point out the irony of Vogue voicing the call for body positivity.

But these accusations aren’t new. In fact, as soon as Rooney published her second and most iconic novel Normal People (2018), X, formerly known as Twitter, users noticed the similarities between protagonists Frances (Conversations with Friends, 2017) and Marianne (Normal People).

This prototype of a girl, which some have labelled the ‘waif girl’, and others have seen as some kind of replica of Rooney herself, is designated by several identifying characteristics. Verging on the invisible, she is socially outcast, ghostly white, and -through a diet of black coffee and self-loathing- physically wasting away.

Adding her third book, Beautiful World Where Are You? (2021) to the mix, seems to bring another one of these avatars. As I read BWWAY, I couldn't help wondering if Rooney was playing some kind of joke in seeing how much casual eating disorder content she could sneak past her readership.

But appetite for her work remains high. We’re left with the questions of who gets to be a Sally Rooney protagonist and whether we should see this as problematic. What sticks out to me the most about her protagonists, is the different rules of representation for men and women. Rooney is praised for the psychological depth of her novels, inviting us deep inside the minds of her protagonists. The exploration of mental health and suffering that this allows is in no way limited to women.

Take Marianne and Connell, the ‘will they won't they’ stars of Normal People. Connell’s struggle with his mental health is one of the most rich and heartbreaking strands of the book, something which really comes across in the BBC adaptation through Paul Mescal’s haunting portrayal of his character’s therapy session.

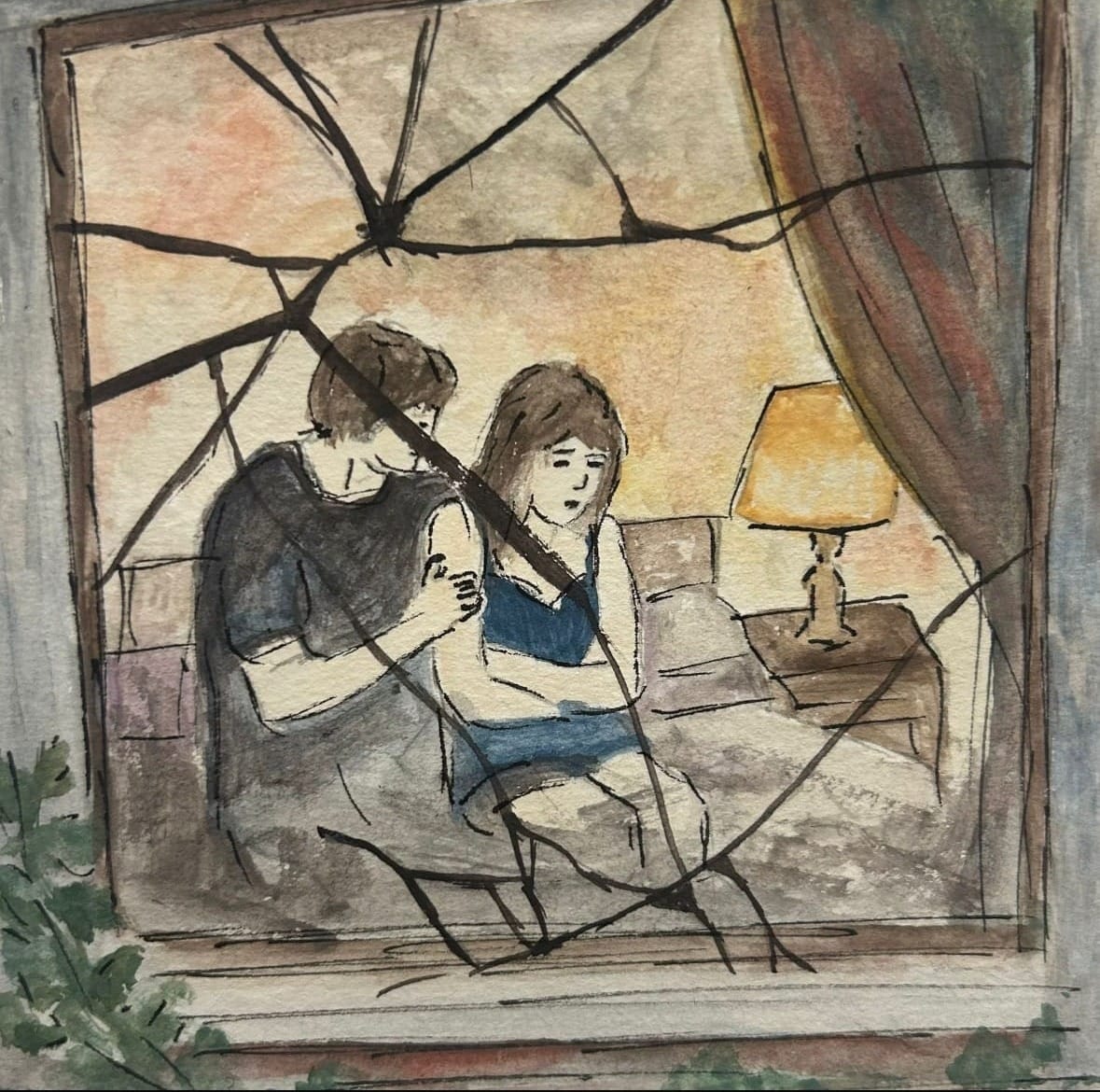

It's clear that male characters are allowed to suffer. It’s also clear that their suffering is allowed to remain psychological. The male body is not forced to starve or sexually degrade itself in order to be worthy of redemption. For Marrianne, her suffering must be validated by her appearance.

Cruelty to the body only seems to be endured by the self-sabotaging female leads, who revel in seeing how bad things can get. The barely disguised suggestion that women must be physically wasting away to be recognised as unwell in the so-called ‘Rooneyverse’ is troubling. Worryingly, the frailty of Sally Rooney’s women also plays into their general childlike quality in which they appear as damsels in distress to be rescued from danger and low self-esteem by their heroic male counterparts.

It's not up to us to strip artistic freedom from the novelist. However, I find I'm amongst many who are sick of the starving female body in Rooney’s fiction. It seems a strange choice to make but stranger to make again and again. And it goes beyond a lack of diversity in the representation of bodies to draw on problematic assumptions about what it means to be mentally ill. The resonance of her novels with the young adult demographic suggests a potentially damaging influence of her work.

This is not to say that young people lack the critical thinking skills to recognise the self-destructive behaviours of her protagonists. But, in an age where social media worships the thin body and diet culture is alive and kicking, is Rooney adding to the pressure on young minds and bodies?

On the other hand, when Rooney caters to a society where thinness is already the norm, from fashion to film to fiction, is it right to hold her more accountable than any other part of the culture? Is the author more or less to blame than the influencer?

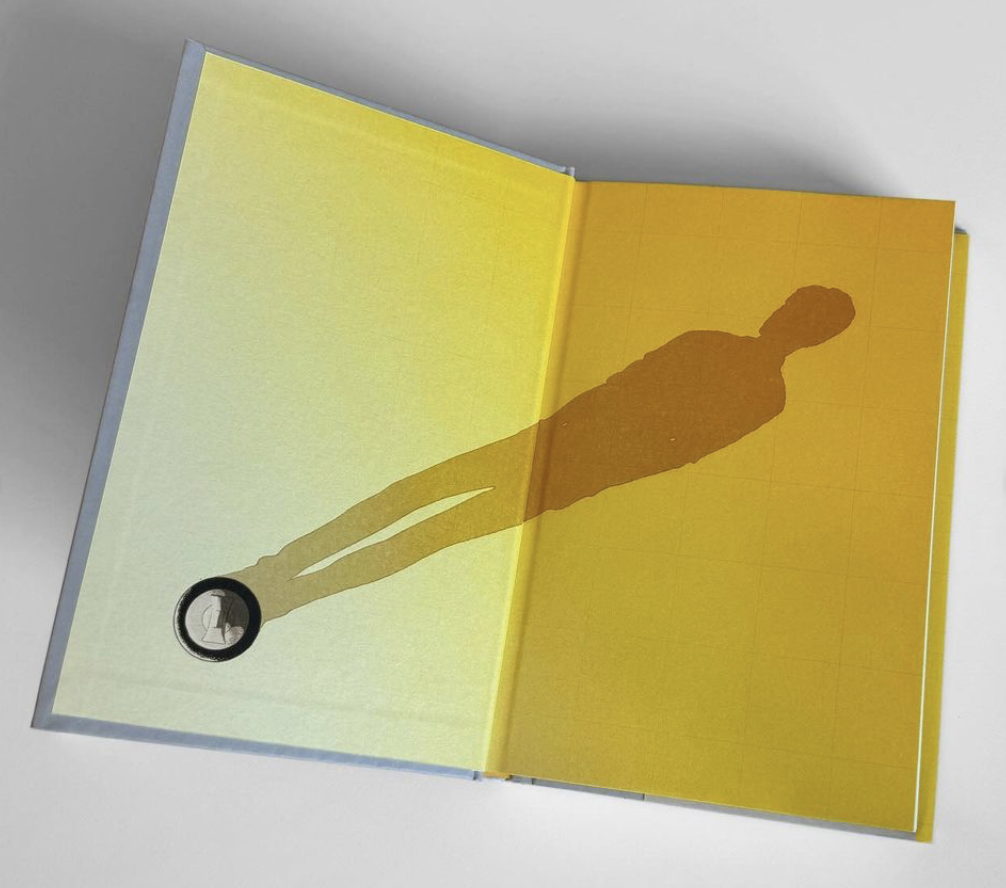

After these broad and pessimistic questions, I’ll end on a positive note. Rooney’s new work. Intermezzo marks a change of direction. Leaving the suffering female body alone, she moves to focus, for the first time, on two male protagonists, something which she tells the The Guardian’s Lisa Allardice is ‘stepping outside my own social reality’ as a female author.

The novel, which is already gaining rave reviews, follows brothers Ivan and Peter as they grieve their father’s death. It’s unclear what has sparked this new direction, as Rooney herself is unbothered and unapologetic about the resemblances between her previous work. However, she does confess her relief at leaving behind her twenties and with them the expectation to speak for the anxieties of the twenty-something demographic (The Guardian).

Perhaps the choice to tackle the complexities of grief and the male psyche is a consequence of her maturity as a writer. It’s unclear where this leaves the depiction of female interiority which readers have come to know. In the long career that Sally Rooney has ahead of her, I hope to see her return to the female protagonist in a way that distinguishes psychological turmoil from bodily harm.

For now, by breaking her own stereotypes, she proves that she can write as widely as she can deeply.