By Ben Glennan, Third Year, Ancient History

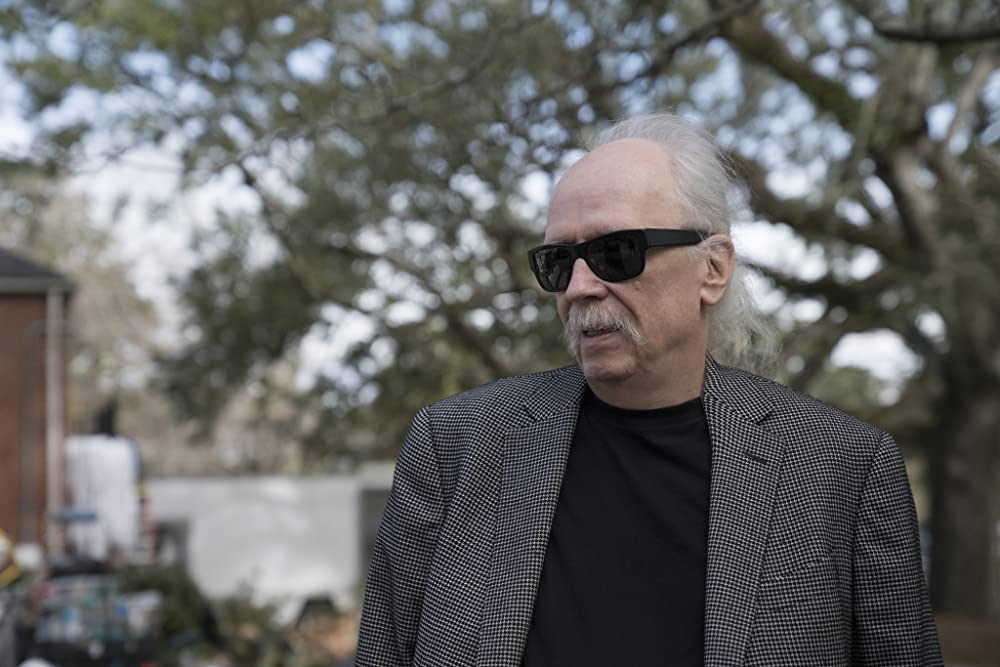

Today, the king of cult himself, John Carpenter, turns 73. Join us in celebrating the life and work of one of the most recognisable and influential filmmakers in alternative Hollywood history.

Writer, director and composer, John Carpenter has crafted some of the most cherished and influential independent films of the last forty-five years. Operating exclusively in the lower budget range, many of his features have been critically panned on release but have gone on to acquire the praise and recognition that his method rightfully deserves. This trend has seen his films become cult staples: from The Thing (1982) to Vampires (1998), Carpenter is often seen as the godfather of independent filmmaking and has left his mark particularly on the horror genre.

Inheriting his flair for music from his father, Carpenter’s films have become as renowned for their scores as their distinct visual style. Carpenter has scored the majority of his work and similar to his directing, his scores are often stripped down and rough around the edges, though easy to recognise. His most famous musical work is undoubtedly his theme for Halloween (1978), becoming synonymous with the genre in general, more people can recognise the theme than have seen the film at this point.

It is said about many directors but seeing ‘John Carpenter’ before the title does mean something unique. Carpenter’s proclivities are present in all his features. He has manufactured a style that is instantly recognisable and beloved. His exploration of urban decay, society’s outsiders and the threat of religious control are all themes that he has touched on and comes back to, always with a distinctive style and entertaining voice.

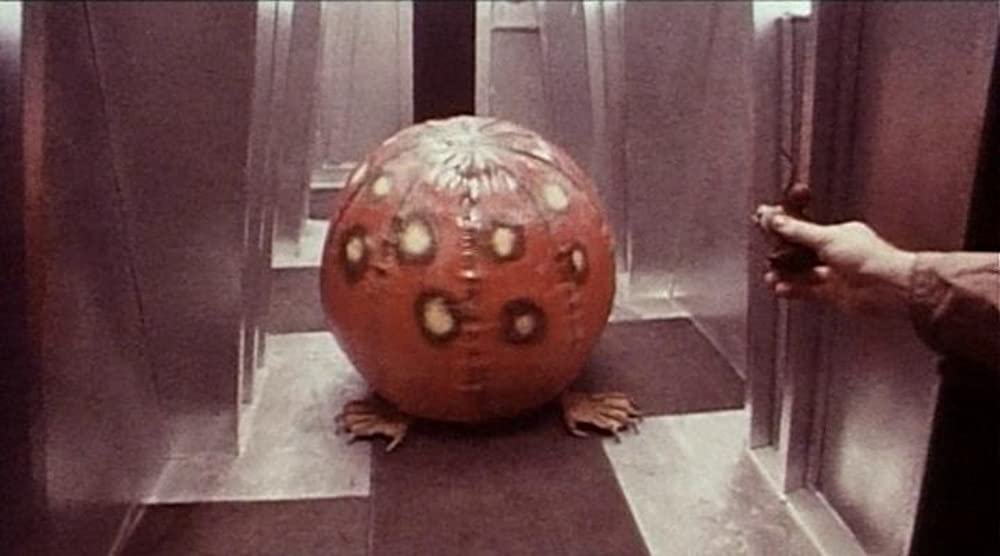

For my money, John Carpenter remains the greatest independent filmmaker perhaps of all time, or at least, certainly the most enjoyable. His commitment to his vision is only aided by his lack of budget: he has always held the authority on where his pictures go and where the lack of finances could create problems. Instead, they provide opportunities for creative and resourceful filmmaking (visions of an alien beach ball in Dark Star, 1974).

Carpenter has always surrounded himself with a like-minded crew that has shared his passion, negating the need to pursue extra financial backing. I have never laughed as hard watching a film as when a man literally explodes from anger in Big Trouble in Little China (1986) or been as disgusted watching a man’s head sprout legs in The Thing. Carpenter’s films are dripping with charm. They may not always be polished, and the acting in specific films is often so bad it goes past being funny, but I still maintain that John Carpenter is God’s gift to cult cinema.

Carpenter was born in Carthage, New York in 1948. Growing up in Kentucky, his formative years were hijacked by westerns and 50’s horror flicks which had an impact on the young man’s later work. Instead of graduating, he left film school to make his directorial debut, Dark Star, a paperclip budget comedy about a crew aboard the titular spacecraft tasked with destroying unstable planets. Much of Carpenter’s later identity has its origin here, but it was not until Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) that Carpenter gained any real critical or commercial acclaim.

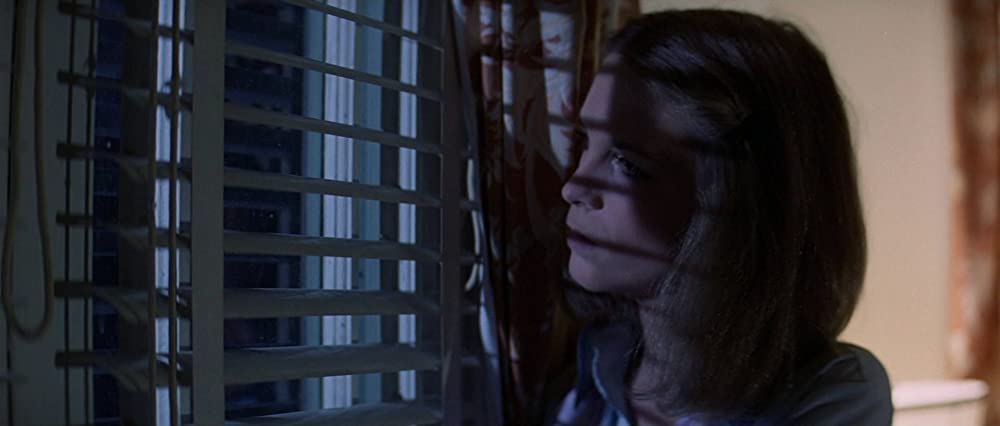

Off the back of the previous films relatively minor success, Carpenter went on to create one of the most influential horror films of all time. Halloween is perhaps the best showcase for what a John Carpenter film is. A distinctly haunting score, the focus on society’s outsiders, an urban backdrop, element of the supernatural: these are all classic Carpenter tropes and were cemented in Halloween. Carpenter gave us a quintessential slasher villain in Michael Myers as well as an archetypal scream queen in Jamie Lee Curtis, with whom he would team up with again in The Fog (1980).

“These movies come from his head, so there’s gotta be something wrong with him!” – Jamie Lee Curtis, John Carpenter: The Man and His Movies (2004)

After Halloween, it became easy to identify a Carpenter film. His fingerprints have remained visible in all his later features. Whether in his more comedic outings such as They Live, or the typical horror flicks like Village of the Damned (1995), Carpenter’s style and thematic focus’ are always present, the humour and sci-fi mystery of They Live for instance famously belying the film’s critique of Reaganomics and it’s not so subtle depiction of Republicans as conservative aliens.

Indeed, there is a sense he has inhabited his films to a degree, their often-supernatural material encouraging a possessive, at times almost satanic connection between Carpenter and the viewer. Usually, I would touch on this sentiment as merely adding to the enjoyment of viewing of In the Mouth of Madness (1994), however, I can confirm that Carpenter or his films are in fact possessed.

Watching Prince of Darkness (1987) a couple of years ago with my brother, at the climactic moment when what is ostensibly the devil breaks through to our world, with Father Donald Pleasance looking on in abject terror, we heard a hiss and smelt what was burnt plastic, as our TV after showing no signs of degradation before this let out a flash and puff of smoke, dying presumably as a result of the demonic signature of the DVD or as we alternatively hypothesised, as a result of Donald Pleasance’s disembodied spirit preventing the demonic force from entering this realm through wrecking our Panasonic. Ultimately, the whole affair only affirmed our affection for Carpenter films, emphasising that his work really can get under your skin, in the best possible way.

Bridgerton is a beautiful, but shallow, feast for the eyes

Vanessa Kirby gives a devastating performance in Pieces of a Woman (2021)

John Carpenter is a staple of cult cinema, his contentment for low budget, rough filmmaking and bare, complimenting scores have influenced countless filmmakers. His horror can be deliciously gory or nail-bitingly tense operating just as well in suburban Illinois as in remote Antarctica. Carpenter came here to chew bubble-gum, and kick ass, and he’s been out of bubble-gum for a good few years now. Here’s to many more.

Featured: IMDb, Ryan Green / Universal Pictures

Which one of John Carpenter's films is your favourite?