By Ellen Jones, Second Year, Politics and International Relations

In Die Another Day (2002), Halle Berry’s ‘Jinx’ emerges from the sea in slow-motion. She wears an orange bikini, and lifts her arms to run her hands through her hair; James Bond (Pierce Brosnan) watches her hips sway as she approaches. “Magnificent view,” he calls to her. “It is, isn’t it?” Jinx replies. “Too bad it’s lost on everybody else.”

Of course, she’s mistaken. Because there’s another central witness to this ‘view’, on whom the camera ensures it definitely isn’t lost: us, the audience, watching the film. We see Jinx first through the lens of Bond’s binoculars because this is how he sees her. The shot tells us that Bond thinks she’s sexy, while at the time telling us: you do too, don’t you?

The treatment of ‘Bond girls’ in James Bond films throughout the years is somewhat infamous. The ‘Sexy Lamp Test’, as coined by comic-book writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, comes to mind: if you were to replace many of these Bond girls with a sexy lamp, would the plot still basically work? There are obviously exceptions, but when the answer is yes, it becomes clear that the purpose of these female characters isn’t a narrative one—rather, they’re there for the viewing pleasure of the audience’s ‘male gaze’.

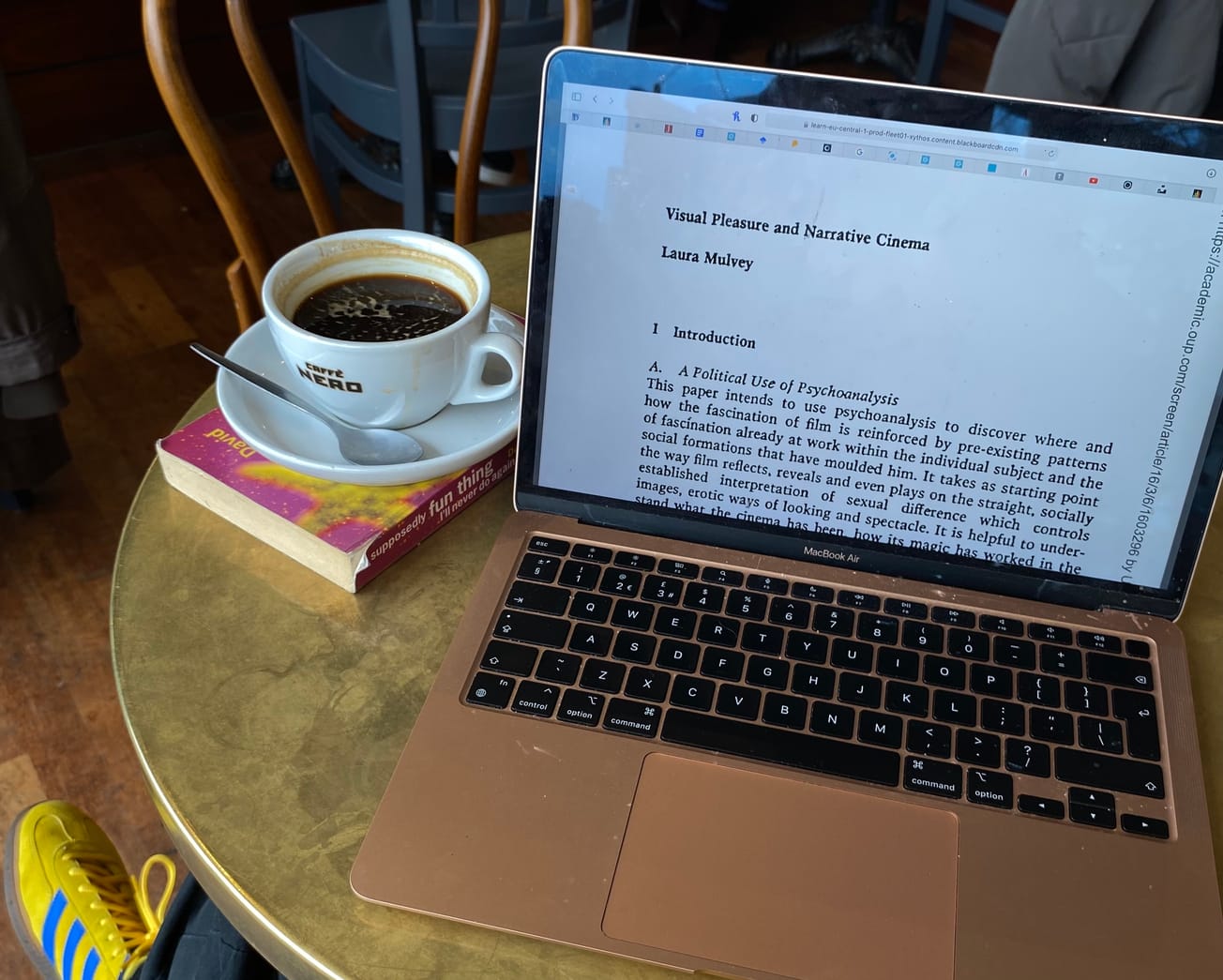

The term ‘male gaze’ originates from film theorist Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. As a microcosm of our wider patriarchal society, it refers to the concept of ‘visual pleasure’ within cinema being split between an ‘active male’, looking, and a ‘passive female’ as the sexualised object there to be looked at, both by the heterosexual men within the media and the audience consuming it.

Mulvey writes that women under the male gaze are usually "coded for strong visual and erotic impact": through the way they dress (think of Jinx’s orange bikini), the way they move (her sway) and the way we, as the camera, watch them do it. It’s present in the parts of the woman the shot lingers on, or creeps closer to (often her breasts, her bum, her legs), and the message conveyed by these choices—these are the traits of our two-dimensional female character deemed worthy of emphasis, with their complexities as people often treated as secondary to their objectification (if considered at all).

What, then, is the alternative? The instinctual response to the objectifying male gaze is that of an equal but opposite lens: a so-called female gaze. But the female gaze is a murkier concept than this: it has no single, accepted definition within theory—nor is it even agreed that such a gaze exists. The patriarchal environment within which we create art might make us sceptical that there can be any portrayal of women that is truly separate from it; and, if there can be, what about those identities exist beyond, or interact with, the binary ‘gazes’ of male and female? What of the queer gaze or the gaze of women of colour? Where do these perspectives fit within this theory?

Perhaps the simplest way to approach defining a ‘female gaze’ is to seek portrayals of women which defy the male gaze, instead depicting women as complex, multi-faceted, and above all, human. In Céline Sciamma’s 2019 film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, the act of ‘gazing’ is examined through the romance between an aristocratic woman, Héloïse, and the female painter employed to paint her wedding portrait, Marianne. In her refusal to pose for any painter, Héloïse rejects being rendered as the passive object Mulvey describes; she deconstructs the ‘split’ between ‘looker’ and ‘looked-at’ by observing those who observe her. “We’re in the same place,” she tells Marianne. “If you look at me, who do I look at?”

My favourite example of this alternative gaze, however, is Phoebe Waller-Bridges’ 2016 comedy-drama series, Fleabag. Again, the gaze here is an important element in its own right: as the character ‘Fleabag’, Waller-Bridge frequently breaks the fourth wall to address us, the viewer, when and how she chooses. The gaze—our gaze—becomes its own character.

What Fleabag demonstrates wonderfully is that to reject a male gaze is not to strip women of their sexuality; Fleabag is conscious of her own sexual appetite, though she habitually employs it in self-destructive ways. But the difference is that Fleabag is never there for our viewing pleasure—when she turns to acknowledge us, she reminds us that we are viewing her because she allows us to. A voyeuristic male gaze is subverted by her control over what we do, and do not, see: she even physically lowers the camera (our ‘view’) when she sleeps with the Hot Priest.

In the closing scene of Fleabag, the audience moves to follow her from the bus stop (in my case, admittedly, through a blur of tears). But we’re stopped when she looks at us—she smiles, and gently shakes her head; the camera stills, and she walks away from us. Here, Fleabag revokes our permission to view her, to follow her—we are left behind, and the show ends. For me, if the ‘female gaze’ ever exists, it does so in the usually implicit defiance of the male gaze which is made explicit in Fleabag’s final fourth-wall break: the idea that when women are looked at through a ‘female’ gaze, we often find them looking back at us.

Featured image: Ella Carroll

What movies or TV shows have you soon that you thought were particularly 'male-gazey'?