By Alexander Sampson, Deputy Editor

‘If we had communicated the facts well enough,’ asserts presenter and paleoanthropologist, Ella Al-Shamahi, ‘COP27 wouldn’t be happening next month.’

As it stands, COP27 is happening and the machine of global discussion, rather than action, lumbers on. This is the predicament facing the world’s natural history creatives, and the dilemma posited before a group of 5 award-winning, world-renowned members of the wildlife film industry at this year’s Wildscreen Festival.

‘We are communicating to the converted very well,’ continues Ella, ‘And we are not communicating to the unconverted well at all.’

Several nods murmur through the audience.

‘What are we doing wrong?’

In an age blighted by disinformation, viral antagonism and entrenching internet enclaves, the digital sphere presents a hostile landscape to explore. Yet this is the frontline for natural history filmmakers across the world in their battle to amplify nature’s voice.

Previously, natural history filming served research, documentary, educational and entertainment purposes. However, with climate change poisoning every natural habitat on earth, the future of the planet’s ecosystems is at stake. The job of communicating this crisis lies in the hands of a small and highly specialised industry struggling to find its voice, and even its place, in the new digital hierarchy.

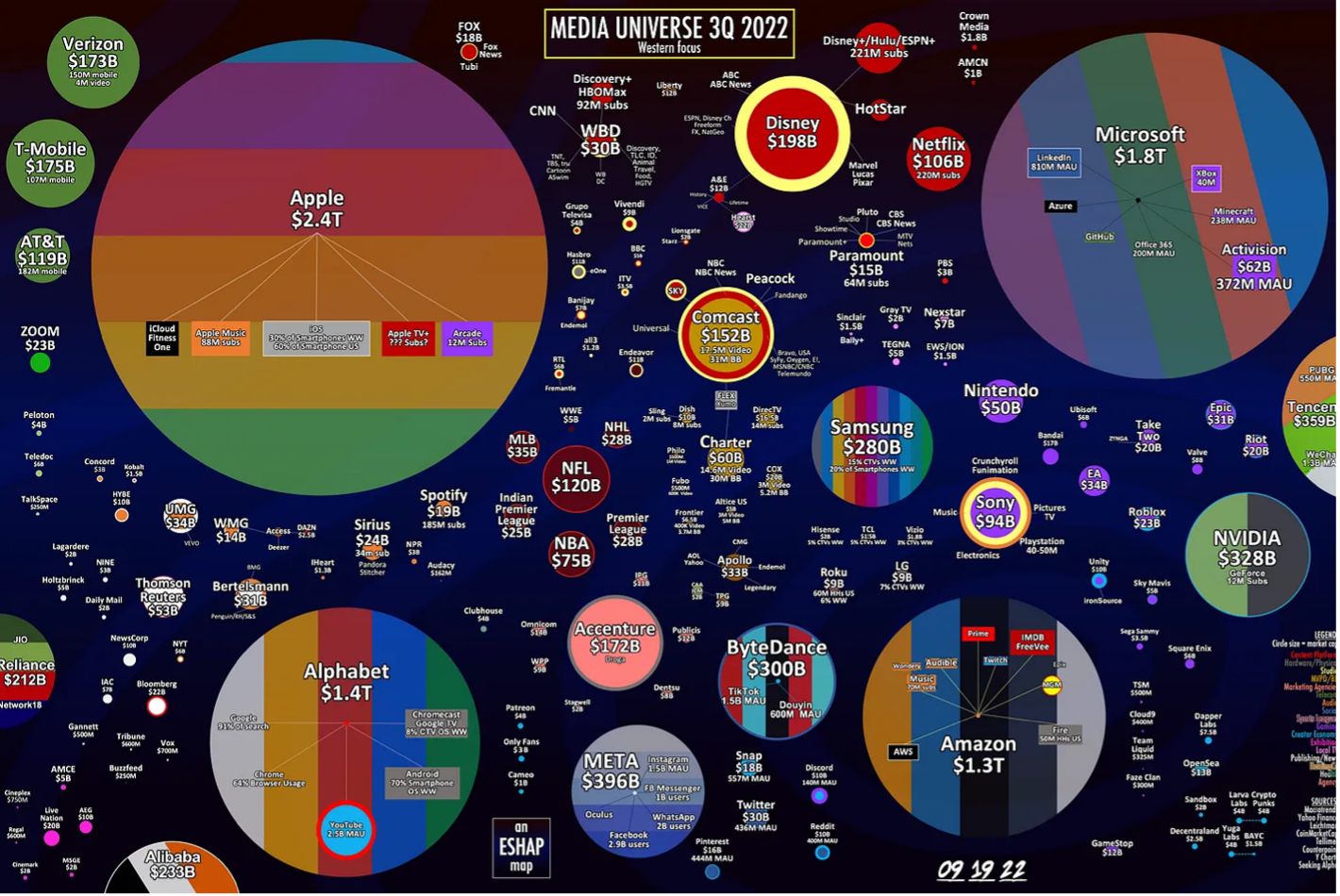

‘Half the problem,’ notes Sam Barcroft, ‘is that the shape of the media universe has transformed in the last decade alone.’ Sam is the founder of Creatorville, a YouTube production company with a vision to democratise content production. He notes that Meta, formerly Facebook, has shrunk from being valued at $1.4Tn in 2021 to $326Bn in 2022. ByteDance has grown by 417%, and the BBC has maintained its meagre $5Bn share.

The people and methods of content production have transformed too. An enormous, incalculable proportion of the content we (the general public) currently consume is produced by non-professionals – customers and consumers working with Amazon tripods on Tik-Tok, filming with iPhones and editing on Canva. The market is so ripe that a quick prayer to the algorithm gods can leave users with millions of views in minutes.

This is not news, but for a documentary-led industry it presents a significant problem. Climate change and social media are working at such rapid rates of change that a 2-year shoot in the Amazon is quickly out of date in terms of facts and demand.

Changing the business and content model is therefore crucial to the survival of the industry, something Cam Whitnell is pioneering with a minnow of the wildlife sector – CBBC.

Cam grew up on his family's zoo alongside his three brothers. He began filming their lifestyle and care for the animals back in March 2020, and has diligently built a social media presence. He is, perhaps, wildlife’s first influencer, and believes that his subsequent recruitment by CBBC and Nikon came as a result of already having a well-established personal brand.

Instead of producing a documentary and then trying to sell it through advertising, he suggests starting with someone who already has a major following and plugging the filming of the series as it goes along. The person is key: ‘People are invested in people. That’s what works now.’

Packaging facts and stories through a likeable personality is certainly the most successful model in today’s digital climate. But it is not just who: formatting is also crucial. In Cam’s words, ‘the future is one minute or less.’

In a streaming world driven by serotonin and cortisol spikes, quick drama sells. Lengthy documentaries – no matter how beautifully shot – don’t reach those who aren’t interested in wildlife or climate change. Nor do many people have time to sit down and catch an hour of Green Planet.

Instead, finding new ways of formatting content, as well as the content itself, is key.

According to Sam Barcroft, we are close to mainstream blended experiences – so close, in fact, that platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are being labelled ‘legacy medias’. For an industry facing an uphill battle in a market saturated with streamable content, the future of immersive experiences and virtual reality may give them the edge.

‘We’re currently in “TV 2.0”. TV 1.0 was traditional film, public service broadcasting and TV services like BBC, ITV and Channel 4. Now we’re in phase two – short form content like Tik Tok, Youtube, Reels and one minute videos. Next we’re headed to “TV 3.0” – the metaverse, interactive, blended experiences of content. But maybe, maybe in 15 years, we will come back to traditional formats.’ (Sam Barcroft)

For the time being, short form content seems to be the industry’s lifeline. But this presents several dilemmas opposed to the established mode. Long shoots and carefully planned projects form the spine of the wildlife documentary, yet truth moves slower than the internet, and research is too dense, long and slow to grab attention in the neon city of Tik Toks and nude influencers.

@christmasdisneycrazylady #documentary #penguin #boring #notboring #funny #fyp #foryou ♬ Ocean Sounds with Music - Ocean Waves Radiance

Sacrificing longevity for wildlife sensationalism – a turtle strangled in plastic, or a violent hunting montage – feeds the internet beast but starves the industry, and the public, of the beautiful, slow and subtle moments within nature.

More factual content is either too dull or too political: a beach covered in oil, or a new gas pipeline through a wildlife reserve raises ire on both sides of the climate change conflict; anger is fought in the comments and not the wild, and deforestation, sewage dumps and illegal fishing continue in the background.

Veering between savagery and cuteness, despair and hope, the wildlife film industry’s content is caught in the internet’s toxic snare.

For David Elisco, an industry-renowned producer, the answer lies in telling a human story: ‘In the feature space it’s not about facts. It’s about story and it’s really, really about emotion. How do you connect with an audience that makes them sit up and engage with the story? [Tell them] about people and what drives them. The responsive chord is that you [the viewer] walk in their shoes.’

HHMI Tangled Bank Studios’s latest offering: ‘All The Breathes.’ Credit: HHMI Tangled Bank Studios

David’s HHMI Tangled Bank Studios is the production arm of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Having won numerous awards since its inception, the studio has successfully produced ground-breaking films about scientific discoveries for over 10 years. David credits this to finding a balance between facts and stories, and stresses that both are equally important:

‘We need to stop trying to convince people of anything; it doesn’t work. We need to start with a story – that’s what people out there are waiting to hear – an amazing story. But let’s not substitute facts for a story.’

Alongside facts and storytelling, Professor Steve Simpson –a marine biologist at the University of Bristol – believes bringing more voices to the table will help. If ‘artists, musicians, academics, authors and the BBC come together’ then change will occur. In Steve’s philosophy, enabling science to ‘permeate society’ will ‘take us to a better place’.

Coupling influential people with scientific projects solves one aspect of the audience-reaching conundrum. And there are many other benefits too: the ‘more people of different backgrounds, interests and fields’ that help convey the ‘reality of wildlife destruction’, the more pockets of the internet this message will reach. Each person brings a new format, a new voice and a new audience. ‘This is how we fix the problem’.

Amidst a ranging debate, the final word goes to Gibbs Kuguru, a shark geneticist and National Geographic presenter. Communicating the existential threat climate change poses to both humans and wildlife, for him, lies within finding mutual ground.

‘I’ve stopped talking about climate change altogether – it’s too big. We need to break the problem down. Rather than talking about carbon emissions and methane, I’d rather talk about clean water and clean air. These are things people can understand and care about.

‘We’re all people; we all kind of want the same things. Let’s find the middle ground and say, “We all like these things, so let’s work towards that”, and the other issues will fall away.’