By Alexander Sampson, Deputy Features Editor

Content warning: contains extended discussion on suicide

If you are concerned about someone, or need help yourself, please contact the Samaritans on 116 123

'Why is Bristol so bad? Why doesn't the University say anything?' Epigram unpacks the issue of student suicides at Bristol, investigating its past, its reality today and the future of mental health services at the University.

In broaching the topic of suicide, I wish to start with the story of my own attempt.

At 15, my world began to close up. Through a complex web of environmental conditions, school culture and a host of other drastic psychological changes natural to puberty, I built high walls and buried my emotions; I learnt to feel nothing, express even less, and slowly became silent.

My silence was replaced by voices telling me I’m not good enough, not worth anything, that no one cared. In the summer, I lay in a pool at night alone and sincerely wished to die.

Through my Christian faith, counselling and huge support from my friends, I began to live again. Over time, I grew increasingly confident in managing my mental health and, coming to Bristol, I felt strong, excited, ready to throw myself into the challenges of university.

Echoes of my past soon caught up with me. In May 2021, news of a student death peeled across the University community and a conversation on suicide roared into life. Casual conversations in student flats and accommodation dining halls veered onto the awful news and the narrative it suggested. I witnessed many similar comments moving along these lines:

‘Bristol is so bad for suicide. The University just doesn’t seem to do anything.’

‘There are support services, but I’ve heard they take ages. No wonder people don’t get the help they need.’

These opinions weave into a wider narrative popular amongst students: namely, that Bristol is a hotspot for student suicides; mental health here is worse than at other universities; the support systems are not good enough; students therefore fall through the cracks.

Amidst this discourse, I began to question why – why Bristol? What was it, what is it about Bristol that means its students suffer so much from mental health issues? Why is its reputation so bad? Why is its suicide rate so high?

Suicide is a very complex issue, highly localised to individual circumstances. Placed in the context of young people generally, suicides are actually lower amongst the student community than in the general 18-24 age bracket. However, the student demographic, especially at Bristol, still holds several unique pressures.

1. Bristol students are amongst the brightest young people in the country. Competing against one another for a coveted 1st means that ‘falling short’ and maintaining a 2:1, 2:2 or 3rd class degree can be unexpectedly devastating. Questions of competency open up issues surrounding identity and value yet tutors and academic staff rarely see students one-to-one on a frequent basis.

2. Bristol’s nightlife scene also attracts students from across the country, with drugs and intense alcohol consumption often forming the backbone of a night out. With the idea of ‘fun’ and/or release attached to extreme consumption, overcompensating for low moods can lead to dependency and/or further mental and physical pressures. Bristol as a city, alongside its student community, holds a strong reputation for substance abuse. Further stats and analysis can be found here.

3. Pandemic-related issues include serious restrictions to social interaction, including the suspension of societies. The overall lack of community has led to many students feeling lonely and isolated in houses or halls. With two years’ restricted socialising, the pandemic’s aftershocks are especially clear in the mental health sector, where surging numbers of people, students particularly, are seeking help for anxiety, depression and loneliness.

4. Arriving at university brings a unique set of challenges all in one go: usually for the first time, students leave their families, friends and home, relocating into a new community and culture without direct support from their previous primary caregivers. Carving out an individual identity means experimenting with new social groups, alongside finding more about oneself in terms of gender, sexuality, religion, politics, appearance – the list goes on. While for some this is very exciting, for others this is incredibly daunting and isolating, leading to a range of mental health issues that can easily spiral.

5. More general factors, collated by Manchester University, include stress-invoking familial issues including bereavement, financial pressures, housing problems and, owing to the pandemic, inability to socialise and connect with others, including family members.

In Epigram’s research, questions have been raised about the ‘type’ of student that Bristol attracts: as a city and university, students raised concerns over whether the perceived culture of drugs, clubbing, left-wing attitudes, art, and music draw in a certain type of person who, amongst these character traits, also has a greater propensity for serious mental illnesses than, for example, the average Exeter or UCL student.

These stereotypes are hard to pin down – arguably, they hold some truth but there is no concrete data to support hypotheses on character, and certainly no homogenous ‘type’ of person who attempts suicide.

What does the data say?

Nationally, the Office for Students has recognised an increase in student suicides year on year. This comes in tandem with a 27 per cent increase in the number of students, from 1.87m in 2010 to 2.38m in 2019. However, there are too many factors marring a correlative link between the number of students and the number of student suicides.

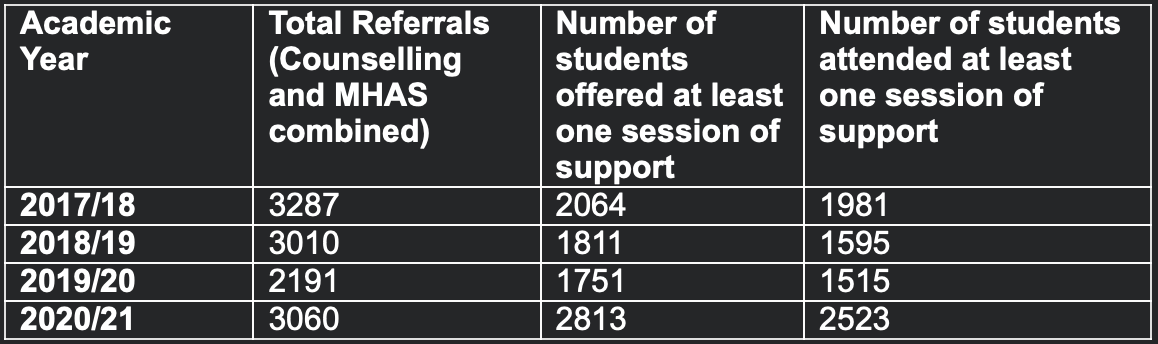

Comparable suicide statistics between Bristol and other HE institutions are also not easily found: the data is not publicly available and a previous request in 2019 was palmed away by the Office for National Statistics. Focusing in on Bristol University’s counselling services, the pandemic years have shaken up the possibility of definitive data analysis – 2019/20 sees a trough in the data, partly owing to many students returning home during the pandemic.

However, some helpful, and surprising, data does exist. In the years 2017-2021, while the average number of students referred for support has remained mostly stable, the number of students offered counselling sessions has significantly increased: on average, 1875 students were referred for counselling in 2017-20, which increased to 2813 in 2020-21. This jump provides a stark reminder of the mental health issues augmented by the pandemic, but also reveals the University’s readiness and ability to offer support to those who ask for it.

What about Bristol’s past?

Reasonably, Bristol does have a history of student suicides: between 2016-2018, 11 University of Bristol students took their own lives. This number, significantly higher than the national student average, was picked up by the national press, resulting in a spate of articles citing Bristol’s suicide ‘epidemic’ owing to its ‘underfunded’ mental health services ‘failing’ in its duty of care.

Such headline sensationalism held its core in truth – there were a number of suicides at Bristol in that period – but inadvertently branded the University of Bristol as the epitome of mental health mismanagement. The press seemingly ignored the similar number of suicides coming from the University of York, instead lambasting Bristol in the public arena.

This sentence has hung around the University’s neck, spreading throughout young peoples’ consciousnesses; 4 years on, Bristol students see news of student suicides as further evidence for this ‘continuing disaster’:

‘Every time there’s another suicide it just confirms this idea that Bristol is really bad for supporting people with mental health problems,’ said a second-year veterinary student.

In the immediate aftermath of these tragedies, the University completely revamped its mental health services. Investing human and financial resources, 2018 saw the creation of the Wellbeing and Resilife services, and major infrastructural changes to the University’s counselling and Disability Services.

Specialists were hired to deal with a range of issues – from counsellors with experience supporting trans people to therapists with diverse racial heritages.

Alison Golden, former Deputy Head of Student Services at Solent University, was brought in to be Director of Health and Inclusion as part of a broad investment and overhaul of mental health services at Bristol. Many of these schemes were ‘in the pipeline’ but were fast-tracked with a 100 per cent increase in spending on mental health services between 2016-17.

What has the University done?

Due to the multi-faceted and complex nature of suicide, the University formed an extensive and exhaustive suicide prevention strategy. Most of this strategy was, and is, long-term: it seeks to prevent mental health crises and suicide both through helping with existing mental health issues and improving the student experience.

As Alison notes, ‘We always think about mental health in that high end – diagnosis and crisis. But on the other end of that is having good wellbeing – life is not a straight road, but we can learn how to look after ourselves better. We’ve invested huge amounts in our community building and positive wellbeing schemes.’

Over the last two years, the restructuring of the Wellbeing Service means that the University has hired a ‘completely new’ Wellbeing Access team this year to ‘triage’ students and send them to the most helpful service based on their specific case.

Wellbeing equally encompasses general happiness. Bristol’s ‘Science of Happiness’ unit came, in part, as a response to rising numbers of students seeking mental health support and is the first of its kind in the UK.

Societies, events and even architecture also form a key part of the University’s strategy; the new library will be a continuation of the Campus Heart scheme which seeks to create a sense of community and cohesion to Bristol’s amalgam of students. The SU Living Room in Senate House is also an area where the SU worked with advisory groups to create a communal space at the heart of the campus. It includes a Sensory Room for students with neurodiverse conditions, a multifaith prayer room and multiple more relaxed study spaces.

We're delighted to launch our NEW #SuicideAwareness training aimed at supporting university students!

— Zero Suicide Alliance (@Zer0Suicide) January 10, 2022

The training supports students, family and friends to see the signs, say the words and signpost to support 👇https://t.co/ttIpL8GyIc#StudentTraining #SuicideAwareness pic.twitter.com/xTUL9B9tWS

Is it working?

Tentatively, the most recent statistics suggest yes – the number of student suicides in the last 4 years has decreased from 6 in 2017-18 to 2 per year in 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21. Each of these deaths is a tragedy. One especially high-profile tragedy in May 2021 brought the spotlight back onto Bristol with regards to student suicides, but the numbers are beginning to write a different narrative, as do several other indicators. Two student suicides per year is two too many; the University has signed up to the Zero Suicide Alliance. The University is working with UWE, Bath and Bath Spa universities to prepare how best to help new students who, emerging from the pandemic, have had a seriously curtailed experience in their final school years.

Notably, Bristol University is being used as a model for other universities’ wellbeing structures. The Opt-In policy – a scheme allowing the university to contact parents, guardians or a trusted friend when there is a serious concern for welfare – was introduced in 2019 and has proved an enormous success. In its inaugural year, 93 per cent of students opted-in, and the policy was invoked 36 times. Multiple universities have since copied the Bristol initiative, and Bristol City Council is also modelling its new support systems on the Wellbeing Services implemented at the University.

‘When I talk to other universities and tell them every service we’ve got, they’re astounded. I can’t definitively say it’s the best, but we have a very well-resourced set-up and there is a huge amount of investment that goes into our wellbeing services,’ said Alison Golden, Director of Health and Inclusion.

What are the students saying?

Beyond the words of those working for the University, Epigram spoke to students across a range of years to gauge their recent experiences utilising Bristol’s mental health services:

‘I requested some support because I was feeling really anxious about some things at home. [The Student Counselling Service] gave me a few one-at-a-time sessions with the same counsellor and these really helped me,’ stated a third-year Law student.

‘In January, I submitted a form to Resilife – I was feeling really overwhelmed. They called me up really quickly – 10 minutes or so – and asked if I was okay, helped me submit some forms for more help and then followed up the next week,’ a first-year Medicine student added.

The most common complaint surrounded waiting times; some students waited up to three weeks for a counselling session in busy times such as January and September. However, according to Alison, ‘Students are perhaps better placed at university because support is much more readily available whereas we see NHS waiting times in Bristol for specialist [mental health] services of up to 9 months.’

‘We have great services, but we are not the NHS – we don’t fulfil their role as a healthcare provider. And the NHS is struggling to meet demand hence things like very long waiting times.’

Considering the University’s position in relation to the NHS raises a key debate: universities are educational institutions, not healthcare providers. Academics cannot stand in for therapists, nor can the University be expected to serve where the NHS is failing. Nonetheless, student wellbeing lies somewhat in their hands.

‘[NHS waiting lists] impact when we want to refer someone on to specialist support but we can’t. We’re doing the best we can, but we’re left bridging a gap we’re not set-up to fill.’

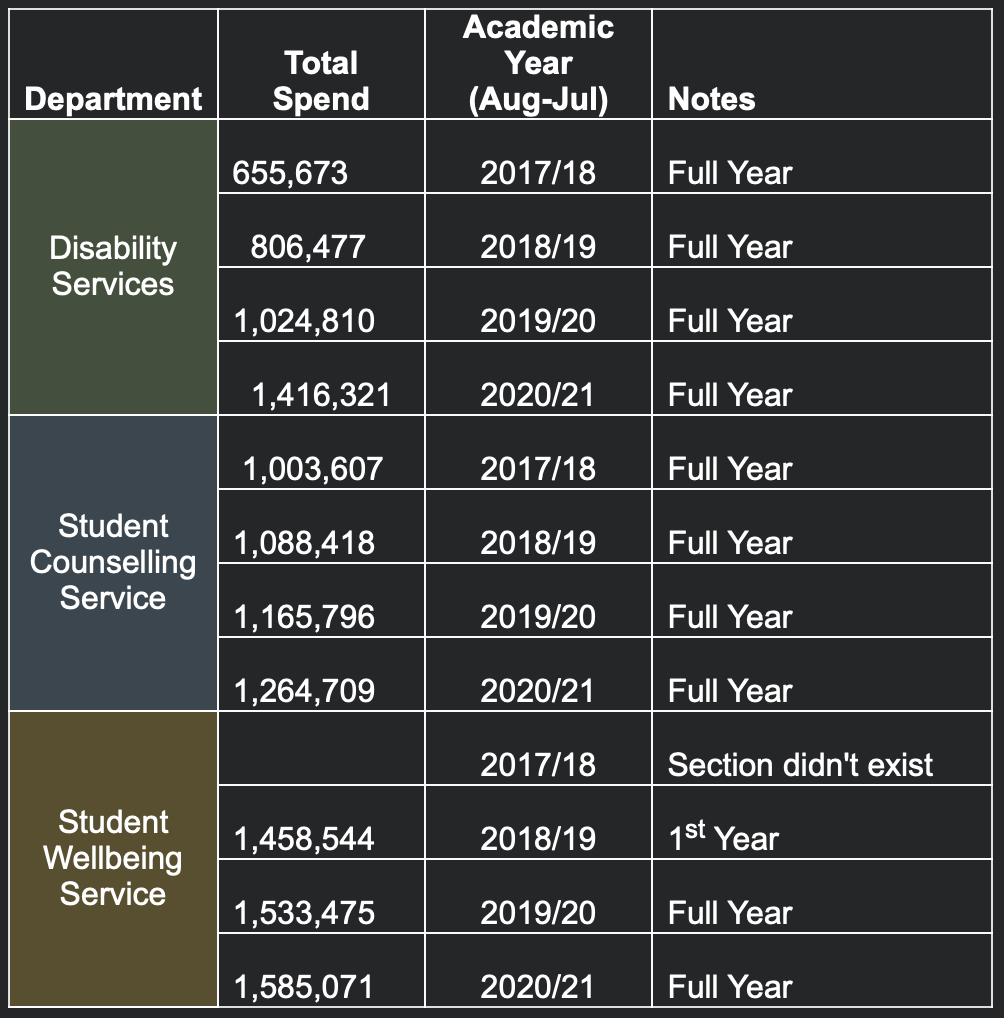

Increasing pressure from students, parents and other bodies involved within the HE sector, alongside the tragedies of student deaths, has influenced universities up and down the country to massively increase spending on their pastoral services. For Bristol alone, financial investment in direct mental health services has increased by 52 per cent in the years 2018-21, with a notable injection of £1.46m in 2018 for the creation of the Student Wellbeing Service. Spending on this service alone has risen year on year to £1.59m in 2020/21.

Disability Services have also seen an increase in spending from £655,673 in 2017/18 to £1.42m in 2020/21, while the Student Counselling Services have seen an 8 per cent increase in budget year on year since 2017/18, accumulating with £1.27m spent on the SCS in 2020/21.

Student-facing staff are required by the University to complete several ‘modules’ on student mental health and wellbeing. However, a recent Epigram article found that not all these are compulsory.

Bristol University’s mental health services are also in constant dialogue with Public Health England, THRIVE – a Bristol City Council initiative, various harm reduction groups for alcohol, drugs and sexual violence, AMOSSHE (Association for Managers of Student Services in Higher Education) – national organisation for training and leadership, Practitioners’ forums for all staff, and Russell Group networks – specifically working with institutions more similar to Bristol.

These investments, initiatives and statistics seem to suggest a serious change in Bristol University’s effectiveness when dealing with student mental health issues. Yet its poor reputation amongst students persists. For some students, it is the University’s silence around suicide that underpins their distrust:

‘When they don’t say anything, it seems like they’re sweeping it under the carpet – like the don’t care,’ said a second-year Computer Science student.

Reporting on suicide

The reality is that reporting on suicide is difficult and mired in controversy. The term ‘suspected’ suicide often appears in the media as it usually takes months to legally ascertain the details of any death in uncertain circumstances; media (often tabloid) coverage of the incident is therefore frequently premature and speculative.

Equally, while the public has a right to know, the wishes of the grieving family must be considered, causing a conundrum for the University as rumours circulate before any official statement can or should be given.

The University of Bristol have provided a statement regarding this:

‘Every student is part of the community we create together at Bristol and communicating about any student death – regardless of cause – is a sensitive challenge. We have taken care to develop an evidence-based approach to our communications, with input from research experts from around the world, Public Health England and guidance from The Samaritans, Papyrus and other organisations.

‘We aim to communicate thoughtfully and sympathetically and ensure that messages are received by the most appropriate people. We will make contact with the student’s family or next of kin, and then our wellbeing teams will try to identify their immediate network of friends and housemates so we can make sure they are aware of what’s happened and where they can go if they need support. Communications are issued to course mates by the relevant school, and personal tutors will follow up with tutees, highlighting the support available to students. Staff in schools are also supported.

‘One of our key priorities is to support the student’s family at what is an incredibly difficult time. It is essential that any external communications, like media statements, are made with the knowledge of the family so we can help manage how much, or how little information we can share publicly. Student deaths are a deeply private matter and, out of respect for the student’s family and friends, as a general rule we would only issue a media statement if asked by a journalist - ensuring the family are aware we have been approached. It is also important that we do not speculate on any potential cause of as this is for a Coroner to determine at an inquest at a later date.

‘We are a community of nearly 30,000 students and 9,000 staff, and we are deeply mindful of the potentially distressing impact an announcement about a student death can have, including on those who have no relationship with the deceased. For that reason, and based on the public health advice, as a rule we do not make University-wide announcements about a student death.

‘There is always more that can be done, and more to learn, and we remain committed to working with students and staff to continually enhance our processes and support services.’

According to Alison Golden, ‘Some of the (media) rhetoric is really unhelpful because it focuses on young people who take their lives. It is very important to recognise these people and tragedies, but it doesn’t account for all the people that have been helped.

‘As a society we tend to focus a lot on students but it’s important talk about “young people” because there are an awful lot of young people suffering who aren’t students – this isn’t just a student issue.’

With Bristol University’s services leading the battle against the mental health crisis in HE institutions, only its storyline is lagging behind. The mental health crisis amongst young people across the country still exists, but a more realistic appraisal of the situation shows Bristol University’s pastoral system is extensive and exemplary. It is not perfect, but its systems are moving in the right direction and the numbers tentatively support this.

Feeling overwhelmed?

— Samaritans (@samaritans) March 10, 2022

Take a moment to pause and breathe 💚🧘 pic.twitter.com/8WT8tDsTr0

What now?

What remains is the issue of “required proactivity”: institutional help can only be granted to those who ask for it, meaning students must themselves reach out. This process requires a series of steps – namely, recognising that they’re not okay, finding and asking for support – which, for someone seriously suffering, is not always viable.

It is these students that are most in danger: according to the charity Suicide Prevention Bristol, 72 per cent of people who take their own lives have not been in contact with any mental health services in the year before their death.

This presents a serious problem: the University cannot help those who they don’t know are struggling. The question then falls onto students – how much responsibility does the student community hold for making sure their classmates, lab partners or general fellow students are okay?

What can students do?

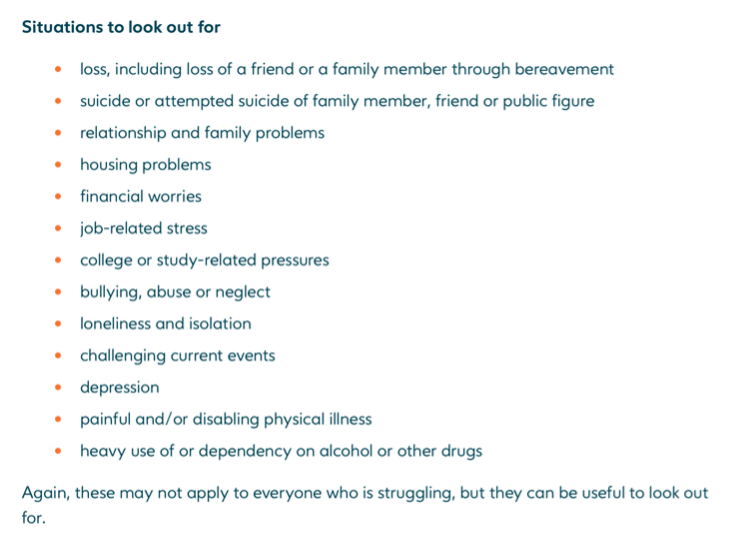

Keith King, a Samaritans Listening Volunteer and Lead Postvention Adviser for Samaritans’ Step by Step programme, suggests that being aware of the behaviour of those around you is key.

‘It’s very complicated […] [the signs of someone thinking about suicide] are dependent on the individual.’

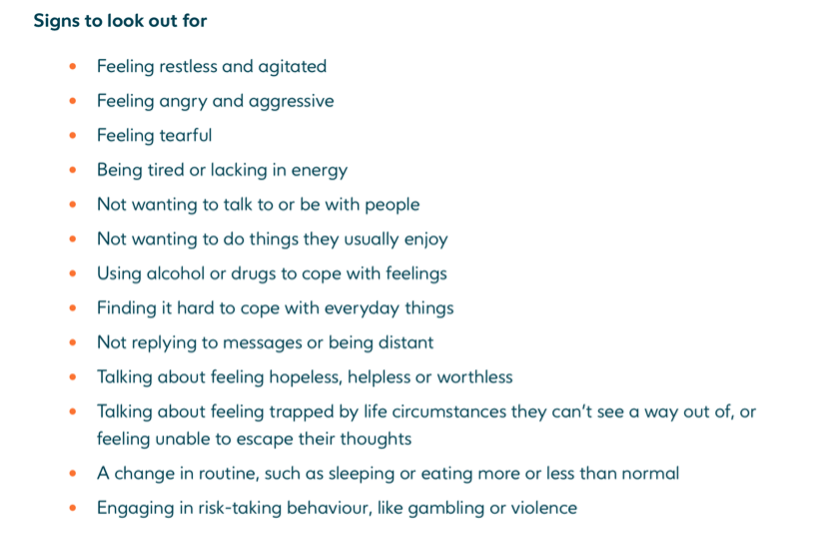

The infographic below details some of the most common signifiers that someone is considering suicide:

‘Listening and empathy are most important. Time too. At Samaritans we search through and ask, explore what they’re saying. What you say and what you do, the words you use, the place you speak to someone (be somewhere quiet), and what you do next – all these are key.’

Samaritans advocate listening, and offer a helpful guide here. However, the charity stresses that you can never force someone to seek help. Equally, if supporting someone who is struggling becomes too distressing, it’s okay to take some time off.

‘It’s important for you to make sure you’re okay too. It’s okay to decide that you are no longer able to help someone and to let them know you won’t be contactable for a while.’

If you are concerned about a fellow student, the University has an anonymous reporting system.

Moving forward

Ultimately, the issue of suicide at Bristol remains an ever-evolving picture. While the narrative around the University is clearly outdated, approaching and looking after mental health within students and young people can always be improved.

Significantly, suicide marks the extreme end of a series of battles, and none of these have to be faced alone. Being at university can be very challenging, but mental health should always be a priority; do not hesitate to reach out to any of the services mentioned, or to ask a friend for support. If anything in this article has affected you, or you would like more information on how to help people, see the links and numbers below.

If you are concerned about someone, or need help yourself, please contact the Samaritans on 116 123.

Whatever you're facing, we're here for you 💚 pic.twitter.com/akIvV86L5H

— Samaritans (@samaritans) March 11, 2022

Other student support services include:

· Young Minds https://youngminds.org.uk/

· Nightline https://www.nightline.ac.uk/want-to-talk/

· Papyrus https://www.papyrus-uk.org/ 0800 068 41 41

· Student Minds http://www.studentminds.org.uk/findsupport.html

· Samaritans Step by Step: 0808 168 2528 / stepbystep@samaritans.org

· Emergency Services: 999

· The University’s DARE TO CARE campaign ran from 28th February – 6th March and aimed to break down the stigma and difficulties surrounding conversations about suicide.

· If you would like to learn more about how you can help a fellow student, the University offers a free, 20-minute course on suicide prevention.

· All University support services: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/students/support/

· Bristol Uni phone numbers:

Featured Image: Alison Needler

If you are concerned about someone, or need help yourself, please contact the Samaritans on 116 123.