By Emily Connor, Third Year, Anatomy

In the aftermath of Halloween, anatomist Emily explores how the human skeleton might not look exactly as you’d expect

We all know that there are certain differences between the skeletons of early humans and modern humans. Most of us will have seen ‘The March of Progress/ The Road to Homo Sapiens’, the 1965 illustration of evolution or orthogenesis from early primates to the modern man.

Yet, has the change accelerated in recent years as our lifestyles have altered significantly?

Humans have had a sedentary lifestyle for many years as we have developed agriculture. This change has resulted in some noticeable skeletal differences in the human skeleton. Modern humans (Homo Sapiens) have more gracile bones, meaning they are thinner and less dense so they generally have less skeletal mass compared to other hominoids. The major downside of having more gracile bones is they have a greater risk of fracture.

The major downside of having more gracile bones is they have a greater risk of fracture

In the world of modern medicine, this isn’t as big of a challenge as it once was because the mortality rate from infections due to broken and fractured bones is much lower than what it was in previous decades. However, this problem can be compounded as we experience decreases in bone density in old age. This can lead to conditions such as osteoporosis.

With the addition of recent technology, such as computers and mobile phones, our lifestyles have changed further from our ancestors - have our skeletons adapted to this change in lifestyle as well?

You may think that there hasn’t been enough time since the advent of smart phones for our skeletons to evolve to fit our increasingly bad posture. In some ways this is true, as there has been no significant genetic shift which has caused changes to the skeleton.

But changes in our skeleton don’t have to be genetic. Our bones are plastic (meaning continuously changing shape to resist stresses), even though you may think of them as solid and brittle. In the same way that our bones can repair when broken and fractured, they can also become denser and increase in size when exposed to increased stress where increased force is applied on the muscle and its attachment to the bone.

As a result, a phenomenon called 'text neck' has occurred. Text neck, is neck pain thought to be due to the increased time that we spend head down and hunched over looking at our phones. This has increased in prominence in recent years, especially in young adults (aged 18-25 years old).

A phenomenon called 'text neck' has occurred

One study found larger and more pronounced (30 millimetres) external occipital protuberance at the back of the neck in this group compared to previous models (eight millimetres). Grazing animals, such as horses, also have this spiny protuberance for the attachment of the nuchal ligament. This helps to reduce muscle fatigue in the neck associated with bowing the head down to reach the grass on the ground for prolonged periods of time.

In humans, the external occipital protuberance is associated with the attachment of the trapezius muscles as well as the nuchal ligament. The nuchal ligament in humans is associated with stabilizing the head during running. However, some critics have discredited this study exploring the back of the neck, citing that it doesn’t measure mobile phone usage in the individuals it measured.

Bristol research reveals how cancer puts brakes on the immune system

How Halloween helped me love my body

So, despite the typical skeleton that you will see in shops this Halloween, the Homo Sapien skeleton is constantly changing and adapting to adjust to our changing ways of life. Many adaptations to fit our new lifestyle could be an advantage, reducing muscular neck problems in our future.

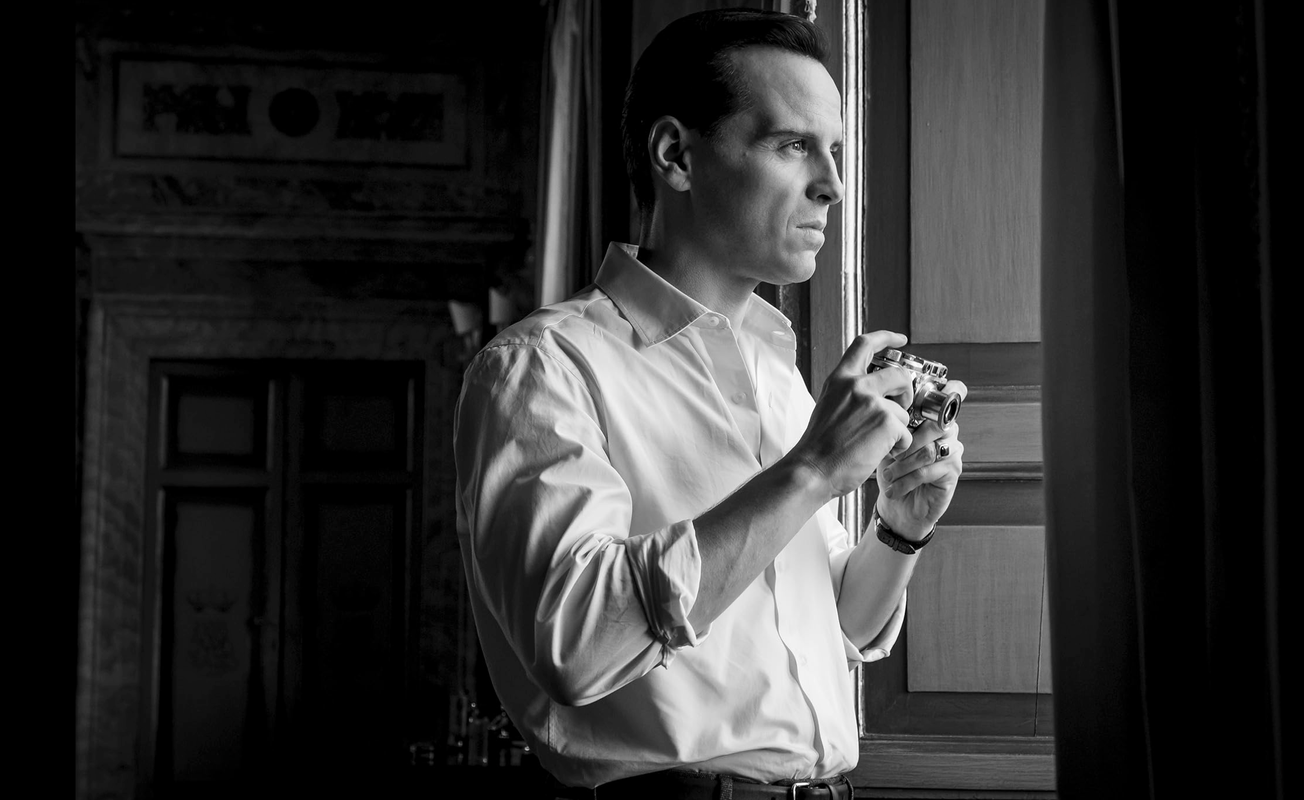

Featured Image: Unsplash/Eugene Zhyvchik

How do you think the skeleton may evolve in the future?