By James Emery, SciTech Deputy Editor

We all know how it feels to be scared, but do you know what actually causes that feeling? Our SciTech Deputy Editor, James, explains.

The fear response is very old and has evolved as a defense mechanism to help us protect ourselves or escape when we’re in dangerous situations. However, it can be easily triggered by things we know are not actually dangerous - better to be safe than sorry I guess!

We all know how it feels when you have a big scare, your heart rate goes up as well as your breathing rate, and you get goosebumps and start to sweat. But what actually causes all these physiological changes when frightened and why do they happen?

We all know how it feels when you have a big scare, your heart rate goes up as well as your breathing rate

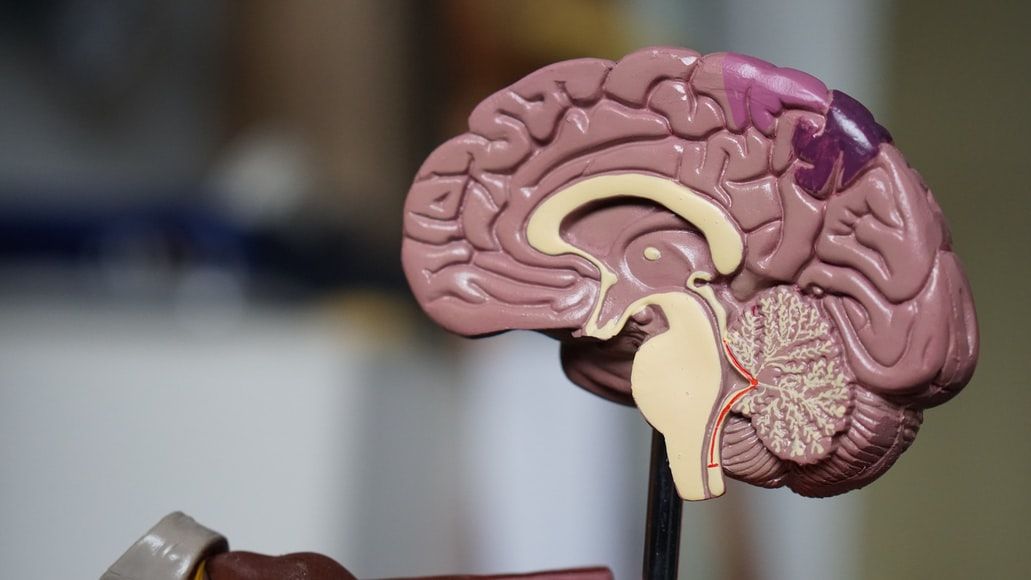

The fear response all starts with a stimulus, whether it be a jump scare in a horror movie, a spider hanging from the ceiling or an ominous bump in the night. This stimulus is then processed by the thalamus, the area of the brain which controls where to send sensory information. When a threat is detected by the thalamus, the information is then sent down two pathways simultaneously, with one being a quick response and the other being slower.

The quick response primes your body for immediate danger without determining whether it is a legitimate threat, whereas the slower response takes time to assess the situation and make an informed decision. This combination of the two pathways is the reason why you are scared for a few moments from a jump scare before you quickly calm down.

During the quick response, the thalamus then sends the threat information to the amygdala. The amygdala, an almond shaped group of neurons which forms part of the limbic system and found in the temporal lobe, helps to process the emotional response and its importance. The hypothalamus will then be signaled by the amygdala to start the fight or flight response.

In the slower path, the sensory information does not go straight to the amygdala but instead takes a detour to the sensory cortex. The sensory cortex will then scan the information for context clues to determine if fear is the correct response, if it determines it might not be then the information is sent along to the hippocampus.

In the hippocampus, it is further scrutinized to apply meaning by checking whether you have seen this stimulus before, and searching for other clues about the danger. If the stimulus is determined not to be a threat, then the hippocampus signals the amygdala which in turn signals the hypothalamus which turns off the fight or flight response.

This combination of the two pathways is the reason you are scared for a few moments from a jump scare before you quickly calm down

So, we have covered what goes on inside the brain but how does that cause the effects in the rest of the body? Well, when the fight or flight response is initiated by the thalamus it activates the sympathetic nervous system and the adrenal-cortical system.

The activation of the sympathetic nervous system sends signals through nerves to the glands and muscles of the body to get ready, also signaling the adrenal cortex – found in the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys – to release adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream. This then causes an increase in heart rate and blood pressure.

Wiccans meet unicorns: the strange evolution of Halloween traditions

Researchers develop an evolutionary theory for the universal stress response

It is this stimulation of the body for action which causes the affects we are used to. For example, the stimulation of tiny muscles under the skin - in the hair follicles - causes you to get goosebumps and the hairs on your arms to stand up. The assumed reason for this dates back to from a mechanism that would puff up our fur to make us seem bigger - back when humans had fur!

Featured Image: Epigram/Sarah Dalton

When was the last time your fight or flight response was triggered?