Charlie Osborne, Third Year, History

The 28th Summer Olympics began last week with an understated but charming opening ceremony, fully encompassing a vision of universal equality, compassion and accord. But beyond Japan’s tracks, fields and pools it is hypocrisy and prejudice, not athletes, vying for gold.

From the IOC’s disqualification of sprinter Sha’Carri Richardson for defying archaic anti-marijuana rules whilst simultaneously condoning Megan Rapinoe's use of the sporting platform to promote her use of cannabinoid products.

From the same committee pledging to champion “inclusion, diversity and gender equality” in February to its announcement in April prohibiting athletes from engaging in political protests or demonstrations during the Tokyo Games.

From the European Handball Federation’s decision to fine the Norwegian Women’s Team for wearing shorts instead of bikini bottoms during a competitive game against Spain last week to their decision to donate that same fine to supporting women in sports.

I knew there was a double standard for uniforms worn by male and female athletes... but this picture of Norway's beach handball team says a lot. https://t.co/qdZBKU7pTK pic.twitter.com/KoWdOvecmr

— Dr. Ji Son (@cogscimom) July 20, 2021

The irony is palpable across the board, and threatens to compromise the unity fostered by sports globally.

There is often a habit of throwing around the term “It’s 2021 (or 2020, or 2019, etcetera etcetera), this shouldn’t be happening”. But whether it be the Euros, the Olympics or any other of a handful of sporting competitions, inequality and prejudice remain rife.

Praising the decision of Germany’s female gymnastics team in wearing full body suits whilst disenfranchising swimmers of African descent in prohibiting the Soul Cap (a swimming cap designed for afro hair, particularly vulnerable to sodium hypochlorite found in swimming pools), hypocrisy reigns supreme and creates a paradoxical grey area for current and aspiring athletes.

Beyond Japan’s tracks, fields and pools it is hypocrisy and prejudice, not athletes, vying for gold

It is clear that not enough is being done. In February, the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Games chief Yoshiro Mori was fired for sexist comments made at an Olympics Committee meeting.

Just one day before the opening ceremony, its director Kentaro Kobayashi was fired for jokes he made about the Holocaust as long ago as the 1990s. Too little, too late.

Whilst the committee has apologised on both counts, constant backpedaling and a failure to properly investigate members at the very top of the organisation signal a deeply rooted issue at the heart of international sports.

IOC Statement on the resignation of Tokyo 2020 President Mori Yoshiro https://t.co/gi9VHztMCq

— IOC MEDIA (@iocmedia) February 12, 2021

Much more must be done to eradicate the inequality that continues to prevail over professional sports.

As long as women continue to receive just 4% of media sports coverage, as long as African American swimmers make up just one per cent of the 400,000 registered USA Swimmers, and as long as 88% of Women’s Super League players make less than £18,000 a year (compared to the men’s average of £50,000 a week), more must be done. This starts at the top.

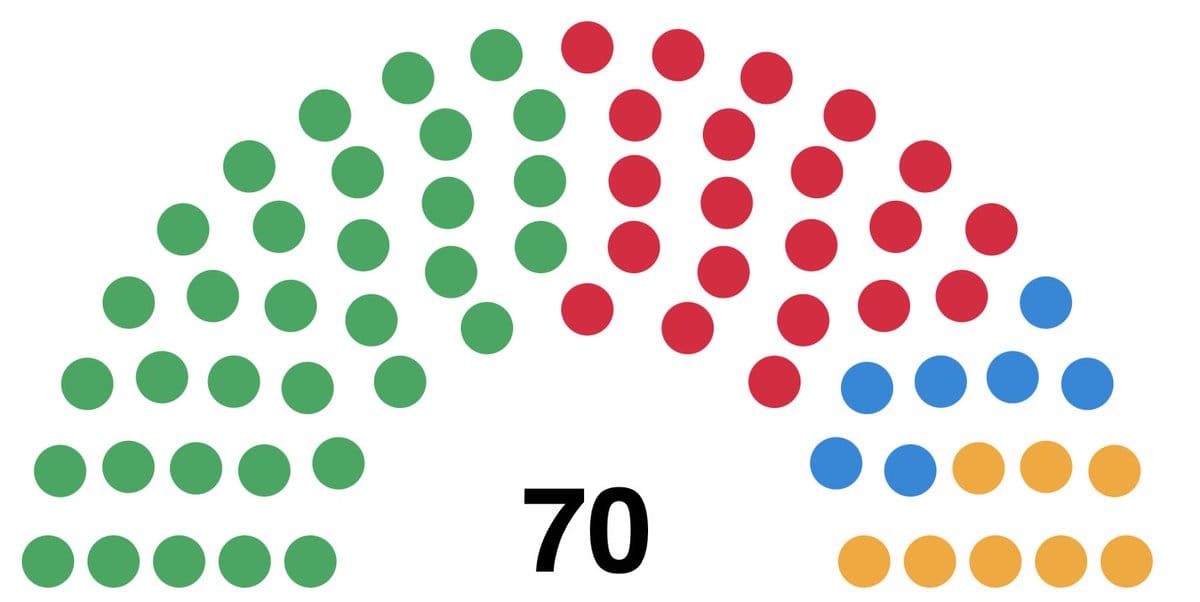

There is, however, reason to remain hopeful. Following February’s debacle, the Tokyo Olympics added 12 women to its executive board, making up 42% of the total members.

Whether it be the Euros, the Olympics or any other of a handful of sporting competitions, inequality and prejudice remain rife

Whilst some suggest this was merely a token gesture, the board’s new president, Seiko Hashimoto, is herself dedicated to “the promotion of gender equality” throughout sport.

Hope on the horizon, perhaps. Further to this, the Tokyo Olympics is stated to be the first gender-balanced games in history, with upwards of 49% of registered athletes recognised as female.

Whilst the Paralympics falls short at just 40.5% of participants listed as female, merit is found in a marked growth on the number of female participants at Rio 2016. More to come in 2024, one would hope.

Opinion | Banning afro swim caps is bad. Excluding minorities from sport is worse

Bristol alumni amongst Team GB at Olympics

If organisations like the IOC fail to pick up the pace, they will continue to disenfranchise potential stars from ever engaging with sport at even a grassroots level.

But as long as public pressure and progressive new faces continue to battle the hypocrisy, prejudice and antiquated mindsets of those orchestrating the world’s most elite sporting competitions, perhaps there is reason to remain optimistic.

Featured Image: Unsplash / Sam Balye

Is enough being done to combat inequality in sports? Do you have any personal experiences? Let us know!