By Livi Player, Arts Editor

With International Women’s Day on the mind, let's look at the dawn of the 1960s ‘Modern Woman’ in Hepburn’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961): a classic movie that cannot be missed.

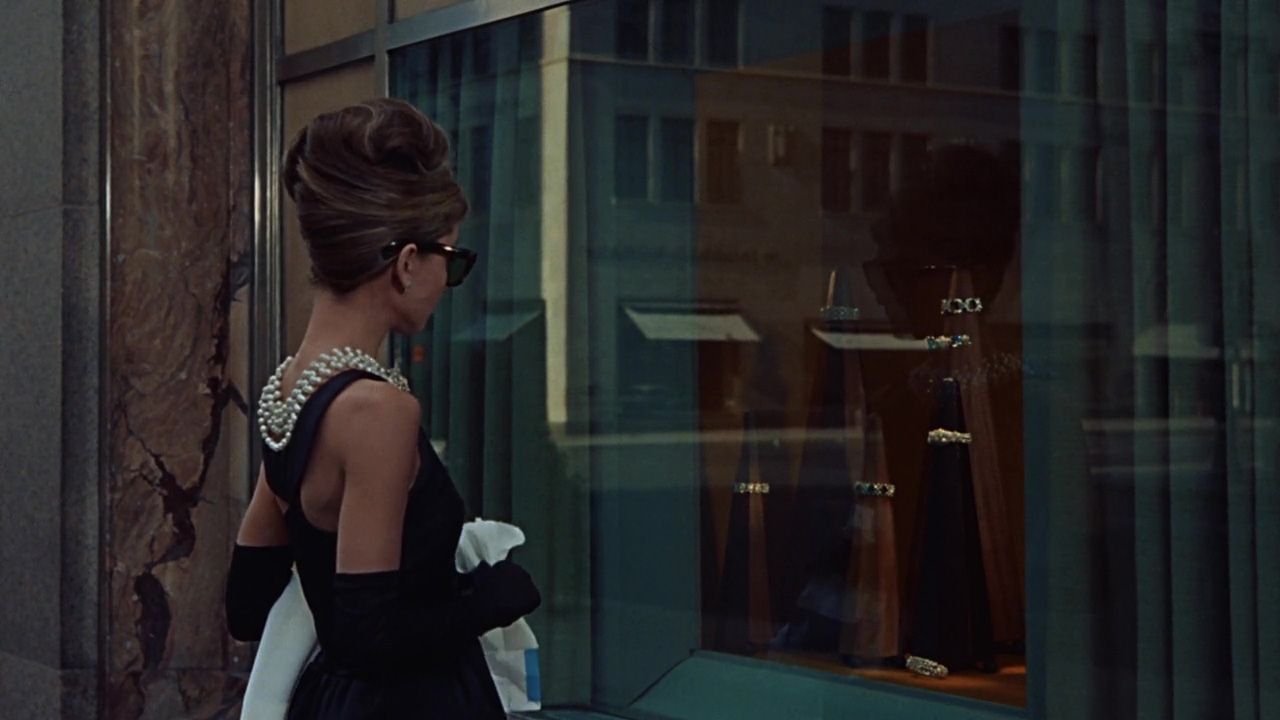

Many are familiar with the name Breakfast at Tiffany’s, not only from the movie with its classic movie poster of Audrey Hepburn as Miss Holly Golightly - wearing the infamous little black dress, ginger cat draped across her shoulders and cigarette holder strategically dangling from her lip, almost seductively. But many forget the novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, written by Truman Capote only three years before the release of the movie to the big screen.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s recalls the story of an unnamed narrator who moves into an apartment in New York City. He makes the acquaintance of his downstairs neighbour: 18-year-old Miss Holly Golightly, a country girl from Texas turned New York cafe society call girl - or as Capote described her, an ‘American Geisha’. She struggles with a sense of belonging, and her eccentric and bizarre personality truly make her a stand-out character in 1960s America.

| Emma adds a sexy spin to the story’s simpering staleness

The movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s, directed by Blake Edwards, showed to be highly controversial at the time of its release. Fifties America, having only just seen the end of the war, saw the subject of sex brought into the forefront of the media. The end of the war saw the return of men to their jobs, sending women back to the domesticity of home life and snot nosed kids, keeping the once approved order and gender lines in check.

Sam Wasson writes, ‘American moviegoers have been devouring a steady dosage of self-image… and in the fifties, if you were a woman, too much of sex was wrong, and too little of it was honourable. You were either a slut or a saint.’ Sex was something not to be spoken about, let alone be shown in cinema. Yet the sixties offered things never seen before in American film; second wave feminism was emerging and women’s voices were finally being heard.

Taking a step back to fifties America and enter the bumbling blonde, the femme fatales of Hollywood, for the fifties was the era of the ‘blonde bombshell’, the ‘blonde sex kitten’ and the ‘sexbomb blonde’. After Marilyn Monroe’s infamous appearance in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), American film demonstrated the clichéd and stereotypical phrase, ‘Blondes have more fun’.

Unsurprisingly the movie made no attempt to explain exactly what Holly does

Blondes became associated with sex and fun, and quickly enough fifties blondes were always cast in acting roles that emphasised their sex appeal, and the ‘dumb blonde’ was formed. Author Richard Koper spoke on how American film presented blondes in these ‘bad girl’ roles who were often the ‘scheming mistresses’, truly heightening the stereotype.

Fast forward to the making of Breakfast at Tiffany's on the turn of the decade and we have a problem on our hands. The choice of casting rested on the shoulders of producers Martin Jurow and Richard Shepherd. Both Jurow and Shepherd knew the role of Holly Golightly was not going to be an easy one to cast.

Being the late fifties/early sixties, the prospect of playing a ‘high society call girl’ was enough to turn many actresses away, including Hepburn herself. Interestingly, Capote even admitted that his first choice for the role of Holly was in fact Marilyn Monroe - because Holly Golightly is actually blonde. Unfortunately, she was already signed onto another film at the time and Jurow and Shepherd were set on signing Hepburn.

| Mental Health & Marilyn - the private pain of one of cinema's greatest stars

Hepburn was very sketchy about taking the part of Holly Golightly, and her choice to take on the role brought up the subject of career women vs wives. The casting of ‘good’ Audrey in the part of the ‘not-so-good’ call girl Holly Golightly rerouted the course of women in cinema, although before accepting the part Hepburn heavily questioned how it would impact her ‘good girl’ image.

Paramount Productions went to every length to desexualise the role of Holly Golightly to match Hepburn’s ‘good girl’ image, leaving only euphemisms to the character’s sexually active lifestyle. I myself had to search the term ‘call girl’ to double check I knew what it meant - because unsurprisingly the movie made no attempt to explain exactly what Holly does - in fact it made every effort to disguise any sense of promiscuity or sexual behaviour.

Sex on screen was always going to be a problem for the screenwriter and producers of Tiffany’s, considering their leading role was a call girl. The Motion Picture production code of 1934-1968 held a set of moral guidelines that were put in place to remove ‘unacceptable’ content in motion pictures. The production code did not allow such scenes as a man and a woman in bed together, marital sex and adultery, to be shown on screen.

The production code was later replaced in 1968 with what we now know as the Film Rating System - PG, 12, 15, 18 age ratings - however this such code heavily impacted the way Breakfast at Tiffany’s could be shown on camera. In fact, both the code’s guidelines and the casting of Audrey Hepburn heavily impacted the subject of sex in the movie.

Before accepting the part Hepburn heavily questioned how it would impact her ‘good girl’ image

Offscreen, it was reported Audrey’s husband, Mel Ferrer, often made the decisions for her, he wasn’t afraid to criticise her work and down-tread her performances. Director Blake Edwards even once said Ferrer would counter direct Hepburn at home, and she would show up on set the following day doing the exact opposite of what Edwards had asked her to do the night before.

Unfortunately, despite Breakfast at Tiffany’s redefining what it meant to be a woman in this new dawn, it was surrounded by male counterparts, and dulled down in promiscuity compared to Capote’s novella.

| International Women's Day Editor's Picks

Still, Hepburn sparked this dawn of ‘The New Woman’ in 1960s New York. Her performance showed Holly’s entire persona was an act to manipulate the patriarchy around her, that living independently alone in New York is a good thing, and that Hepburn’s flexible image from her previous roles as a ‘good’ Audrey to high society call girl Holly Golightly was a step in the right direction for feminism in America’s anxiety ridden sixties.

Featured: IMDb / Paramount Pictures

Did you realise the impact Breakfast at Tiffany's had on women's collective image?