By Elena Venturelli, Second Year Physics

Content Warning: This article includes personal accounts of suicidal ideation and attempt.

The Croft Magazine // PMDD affects around 5-10 per cent of women. Despite this, many women still go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Elena shares her experience of living with PMDD.

My experience with Pre-menstrual Dysphoric Disorder (which affects an estimated 5-10 per cent of women, most of which probably aren’t even aware of it) addresses a wider issue of the outrageous lack of funding in women’s health. Most drugs currently on the market were designed with men in mind. Not only that, this country has an appalling habit of ignoring the major effects that women’s hormones have on their overall health. I challenge anyone to tell me that feminism is in any way obsolete.

The name for this condition comes from it being akin to a very severe form of PMS (Pre-menstrual syndrome). In reality, PMDD is essentially an extreme genetic sensitivity to hormonal changes within the body, ovulation being among the most dramatic of those hormonal changes, which is why symptoms normally occur in a cyclical pattern, continuously triggered by ovulation which occurs seven to ten days before menstruation. The lack of research into this condition is incredibly frustrating. I saw a quasi-misogynistic article in a major newspaper not that long ago claiming that PMS doesn’t exist, and that symptoms women have are completely normal. My clinician told me they were attempting to rename PMDD to something more severe sounding because of issues surrounding the belittlement of PMS, and the fact that since treating people they have found that ovulation isn’t the only trigger.

I was diagnosed with PMDD (Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder) in 2017 after two long years of feeling completely misunderstood and desperately alone. I am one of the lucky ones - most women suffer for a lot longer. 50 per cent more women than men are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and the best explanation for this is that women with PMDD have been misdiagnosed, due to many of the symptoms being almost identical.

Women with PMDD tend to have mainly psychological symptoms which include depression, suicidal thoughts, very intense mood swings, lethargy, over-excitement, anxiety and extreme sensitivity to both prescribed and recreational drugs. I am personally triggered by alcohol, caffeine and sometimes even too much artificial sugar. Other women I have met with my condition share a similar experience that symptoms seem to come in ‘energy waves’.

The obscurity of my conditions means that, although 5-10 per cent of women are affected there is only one NHS practice in the whole country that treats it. This means the current chances of any affected woman getting the correct treatment, assuming they are lucky enough to be diagnosed in the first place, are close to none.

Most people I have spoken to have little or no clue what PMDD is, let alone the impact it can have on a woman’s life. This includes GPs and mental health professionals – trust me I have seen a lot them.

PMDD is a lifelong condition and there isn’t a cure. Getting diagnosed is hard enough, because barely anyone knows about it, and many of the treatments available for the symptoms (such as antidepressants and contraceptive pills) are likely to make it worse (due to the whole issue being a physical sensitivity). Many women result to experimenting with various alternative methods and lifestyle changes to make their condition manageable, which normally takes years.

According to statistics from ‘The Recovery Village’ website, 30 per cent of women with PMDD attempt suicide, and you are 70 per cent more likely to experience suicidal ideation if you are a woman with PMDD, compared to a woman without.

Last week, I admitted myself to A&E because I was considering suicide, I was having mood swings every few hours varying between deep depression and complete elation. I told them about my PMDD and that I believed it was the cause. The first doctor I saw told me the plan was to ignore hormones for now, and he promised to put a psychiatric team on my case. I was put under 24hour observation where I was given a bed without bedding, I had to ask 3 times for water and eventually got a blanket too. I was seen after a sleepless night by a mental health doctor. She seemed very good, but by that time I was in a good mood and spoke well, and she told me I don’t show sufficient signs of bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder, so she sent me home immediately with a few leaflets with numbers for crisis teams. As I left, I noticed a sign outside saying that the hospital was rated ‘Outstanding’. Later that day I tried to jump out of a window at the doctors’ surgery, because I was in agonising emotional pain and something snapped in my brain that convinced me that the world was pure evil and not worth living in.

I don’t blame any of the health practitioners for what happened, they don’t have the knowledge or means of treating my condition, and there isn’t a proper medical system in place for PMDD sufferers.

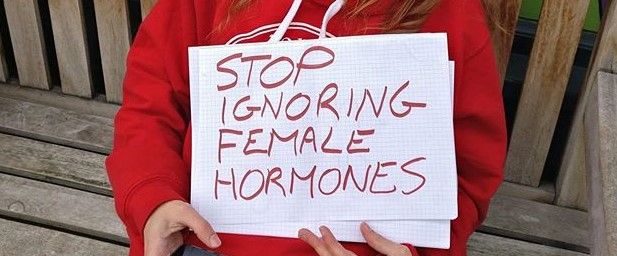

Since this incident, that I can only refer to as mental breakdown, I have decided that enough is enough, and I want to spread as much awareness as I can. Part of my recovery so far involved me walking around campus with a hand-written sign saying ‘STOP IGNORING FEMALE HORMONES’ on my 20th birthday, as seen in the above image. I needed to feel I had a purpose.

50% more women than men are diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and the best explanation for this is that women with PMDD have been misdiagnosed, due to many of the symptoms being almost identical.

As I’ve mentioned, I am very lucky because my family can afford for me to see a private clinician in London who has been personally researching PMS and PMDD for years. Thanks to a £400 blood test, it was found that my natural oestrogen and testosterone levels were so low that they didn’t even show up on the scale. My family isn’t rich, but they are extremely supportive and have pushed very hard for my treatment, which consists of transdermal gels that I rub into the skin on my arms every night. I wouldn’t have been able to finish my A-levels without what I have previously referred to as my ‘miracle gels’. I saw a staggering improvement in my mental and physical health, but as I said there isn’t a definitive cure, and my condition has worsened again since.

There are also long-term physical effects to having PMDD, the major one being a high chance of developing osteoporosis (crumbling bones) which normally occurs in old age. My clinician tested my bones for free as an experiment, and despite being only 19 at the time I have osteopenia (weak bones - not quite crumbling yet). Fortunately for me my hormone gels should prevent this condition from deteriorating.

My clinician has a theory that I find incredibly interesting regarding PMS and PMDD both. The cause may be evolutionary: women’s main function in society for thousands of years has been childbearing, only 150 years ago most women would spend most of their lives pregnant or breastfeeding, hence the evolution of female brains hasn’t been able to catch up with this drastic change in lifestyle, causing many hormone-related mental health issues for women.

From this, it seems obvious to me that life for many women is still very much of a struggle, and the government doesn’t seem to be doing much to help. There are also suggestions that autism in women (another very poorly funded area) is linked to PMDD. Maybe tackling the issues of poor funding into women’s health could result in a faster increase in women in STEM industries and high-power jobs.

Starting an Instagram: pmdd_awareness

If any of the issues in this article affect you, you can contact and talk to any of these organisations.

Samaritans - for everyone

(116 123 jo@samaritans.org)

Papyrus - for people under 35

(0800 068 41 41; selected hours. 07786 209697; pat@papyrus-uk.org)

Childline - for under 19's

(0800 1111 - number won't show up on your phone bill)

Bristol Nightline - for Bristol students

(01179 266 266 - 8pm-8am)

or visit the University's Wellbeing Services

bristol.ac.uk/wellbeing

Featured: Epigram / Elena Venturelli

Find The Croft Magazine inside every copy of Epigram Newspaper