By Vilhelmiina Haavisto, Deputy Science & Technology Editor

Three decades after the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, Bristol scientists are mapping the lingering radioactivity.

April 26th this year marked the 33rd anniversary of the nuclear accident at Chernobyl, north of Kiev in what was then Soviet Ukraine. Most of the nuclear fallout from the reactor meltdown and fire landed within a 30km radius of the plant, and the surrounding area has been of scientific interest for many years.

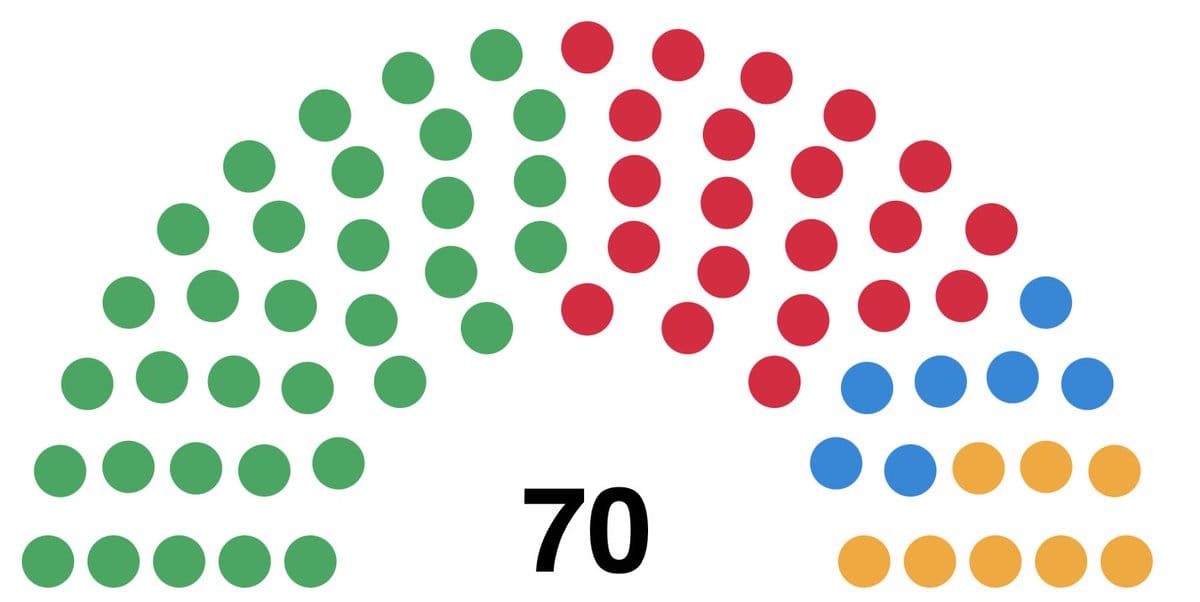

Recently, researchers from the University of Bristol (affiliated with the National Centre for Nuclear Robotics) ventured into the 2000km2 exclusion zone around the Chernobyl plant to conduct radiation mapping using unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones. These included the first-ever mapping of both gamma and neutron radiation. Their efforts produced the highest-quality radiation map of Chernobyl exclusion zone to date, and alerted local authorities to radioactive hotspots that were not known to them before, whose radioactive elements will likely render them dangerous for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

The gamma-ray spectrometry mapping technology onboard the drones was developed by scientists working at the University of Bristol, and has been used to assess the surroundings of the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan which experienced its own disaster in 2011. Because the components of the detection machinery weigh just 500g, the system as a whole is more versatile than traditional mapping systems and can be thus transported on an airplane-like drone. This makes it much easier to characterise areas that would otherwise be inaccessible or painstakingly slow for a ground-based surveyor to navigate on foot.

The new drone mapping technology also means that surveyors do not need to expose themselves to radiation, as the machinery includes a pre-programmable GPS and the drones themselves are fully autonomous. This possibility for relatively remote mapping is incredibly important, as although radiation levels at Chernobyl have decreased enough that visitors accompanied by guides are allowed to briefly tour the exclusion zone, radiation is ultimately still an issue, especially near to the reactor itself.

On this latest trip, the main objective of the research team was to survey multiple areas of interest in the exclusion zone, particularly what is known as the Red Forest because of the distinct reddish-brown colour of the pine trees there, that died after absorbing incredibly high doses of radiation after the 1986 accident. There are still areas of the Red Forest that are unsafe for humans to be in for extended periods of time, which is where the drone-borne mapping technologies really shine. Professor Tom Scott of the School of Physics at Bristol commented that the trip “provided a great training opportunity for [his] PhD students”, and that the mapping technology used there is also “an excellent demonstration of capability for UK robotics and sensor technologies”.

One area of interest for the team was the village of Buriakivika, which was abandoned after the accident due to its location in the middle of what is known as one of the ‘fallout plumes’; a long, thin area of high radiation extending from the main site. The drone-captured footage of the former village shows a dusty, yet wooded landscape; tall trees surround houses, mostly without windows, whose walls and roofs are either crumbling or already collapsed. Indeed, the trees are major radiation sinks, with levels of ionizing radiation around 300 times higher than the UK’s average background radiation.

Although human visits to the exclusion zone are strictly regulated, there is evidence to suggest that animals and plants are already beginning to recolonise the area, in spite of high radiation. In the ITV News report of the project, Professor Scott noted that “Mother Nature is doing its job” in some areas, where radiation levels have actually fallen significantly. A 2016 study found that 14 mammal species, including the gray wolf, the red fox, and the Eurasian boar, had regular visitation rates in the Chernobyl exclusion zone and did not appear to be avoiding highly contaminated areas. In fact, some ecologists believe that the complete absence of human activity in the exclusion zone for 30 years has contributed to the restoration of the wildlife there, and has perhaps inadvertently turned it into one of Europe’s largest nature reserves.

Tourism in the Chernobyl exclusion zone is also on the rise, and the Ukrainian government are even entertaining plans to build a solar power plant in the area; this is made possible by the former nuclear plant’s connections to the electrical grid, which are still in place. The information on where radiation levels are low enough to permit relatively safe human visitation that the new radiation maps are able to provide is and will continue to be crucial, as the future of Chernobyl as an eccentric tourist destination, solar power plant, and possibly even nature reserve, comes into focus.

Featured Image: Flickr / Jorge Franganillo

Want to get involved? Get in touch!