By Felicity Gardner, Second Year, Physics

There has been a rising number of female characters in films with a ‘badass’ streak as a response to the Time’s Up campaign. The trope, however, rejects the multifaceted personalities of real women and reinforces the idea that feminists have to be strong and unkind.

A ‘strong female character’ has become a catch-all term. In action and thrillers she is the leather clad bad-ass or the femme fatale, in dramas she is any character in a traditionally male role or a woman with some autonomy. The bad-ass might have a rank or recommendation proving their worth, yet often they will still have to show their strength before the audience believes it. Think of Agent Carter in Captain America: The First Avenger (2011): we know she is a highly ranking officer and valued by her peers and seniors, yet we still need to see her punching one of the recruits before we accept her as competent.

IMDb / Captain America: The First Avenger / Paramount Pictures

These badass characters are intended to be a rebellion against traditional gender roles, yet they have become characters that shame other women who don’t rebel. They fall into traps of wanting them to ‘man up’ and suggest that, because they are not like other girls, they are stronger or better. The idea that rejecting femininity makes you strong creates an antithesis in which other, more feminine, characters are presented as weak.

These characters also often don’t rebel as successfully as you might think at first glance. Throughout the movie they regularly follow the orders of others and rarely make their own choices in key moments. At the climax of the movie, despite having proven they are far more able than most protagonists, they often step back and let the male hero take the lead. Wyldstyle (Elizabeth Banks) in The Lego Movie (2014) is a prime example. Even after the reveal that Emmett (Chris Pratt) is not destined to save the day and a large part of the movie focusing on his incompetence, he is still the one to face off against Lord Business.

Female characters also get excused for excessive violence as they are automatically assumed to be less threatening - they display traits of toxic masculinity to prove they are far from feminine. In Captain America, for example, Agent Carter frustratedly shoots Captain America while he’s holding a prototype shield. In Edge of Tomorrow (2014), Emily Blunt’s character, Rita, kills the protagonist - out of necessity, it should be said - multiple times with unnecessary levels of violence. Being a strong character rarely seem to go hand in hand with being a kind, or good character, with a character having to be hard to be strong.

Gal Gadot on James Cameron's criticism of #WonderWoman: "It was like he was looking for publicity and I just didn’t want to give him the stage.” https://t.co/0wzbUBgRNb pic.twitter.com/noiFL8HaDL

— IndieWire (@IndieWire) January 9, 2018

James Cameron criticised Wonder Woman (2017) comparing the titular character to his own female protagonist, Sarah Connor in Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991), in an interview with the Guardian. He says Sarah Connor was ‘strong, she was troubled, she was a terrible mother, and she earned the respect of the audience through pure grit.’ He says characters like her are needed as half the audience is female, but surely there should be diversity in the way strength is portrayed? Patty Jenkins replied to this interview on Instagram saying: ‘If women have to always be hard, tough and troubled to be strong, and we aren’t free to be multidimensional […] we haven’t come very far have we.’

The femme fatale heroine started as a villain trope, but with evolving views on female sexuality the character type has become a heroine, so it’s unsurprising that they are often morally ambiguous. The badass is also usually single minded and violent, and the concept places being kind and good in conflict with being strong. This again comes from the idea that strong women and classic femininity are conflicting, with kindness often being seen as maternal.

In The Girl with All the Gifts (2016), Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017), and Aliens (1986) however kindness doesn’t detract from the character’s strength. In fact, it does the opposite. It begs the question: why are kind, strong female characters so rare, especially when many are framed as heroes? This is why Wonder Woman is so refreshing. The film makes it clear she wants to protect the little guy rather than just defeat the baddie, but it’s executed in a way which doesn’t conflict with her strength.

IMDb / Aliens / Twentieth Century Fox

Previously, female characters were not prominent in films, instead being mostly used as a plot device or to develop the main character. As such, these characters, unlike real people, displayed little to no autonomy. Nowadays, whenever a female character acts of their own volition, it’s seen as remarkable. We shouldn’t consider them remarkable, instead we should expect this level of autonomy as the minimum and praise any character who resembles actual women.

A large problem with strong female characters is that even if the character is underdeveloped, falls into the traps of the trope, or is just plain boring they are usually still praised for inclusion. There is such a clamour to include strong women that the more important task of having multidimensional characters falls by the wayside. This can be seen in Mary Sue characters especially, with the writers so afraid for their characters to be criticised as ‘weak’ that they remain unflawed, uninteresting, unrealistic, and unlikable.

there is no one way to be a strong female character pic.twitter.com/iN4rTpgWZv

— Netflix Canada (@Netflix_CA) March 8, 2019

Strong female characters are overpraised. It should not be the case that just because a character can shoot a gun, they are a good character. We should praise characters who are developed and multifaceted. The bar for a character being strong is so low that if Sherlock Holmes was gender-bent, they’d be labelled as this ‘strong female character’. It is a term applicable to far too many characters to be a good metric for whether a character is worthwhile.

We don’t need characters who rebel against femininity, but rather characters who rebel against roles that would usually be assigned them, that aren’t merely there to support the protagonist. We need characters who show that femininity and strength are not exclusive, like Honey in Big Hero 6 (2014), and characters who show you do not need to be unemotional to be strong, like Katara in Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-2008), we also need characters who are morally ambiguous, Atomic Blonde (2017), and more masculine - without criticizing others for not being - and any other type of strong female character. We don’t need what strong female characters are becoming: a lazy, toxic trope that is used in place of using a realistic character.

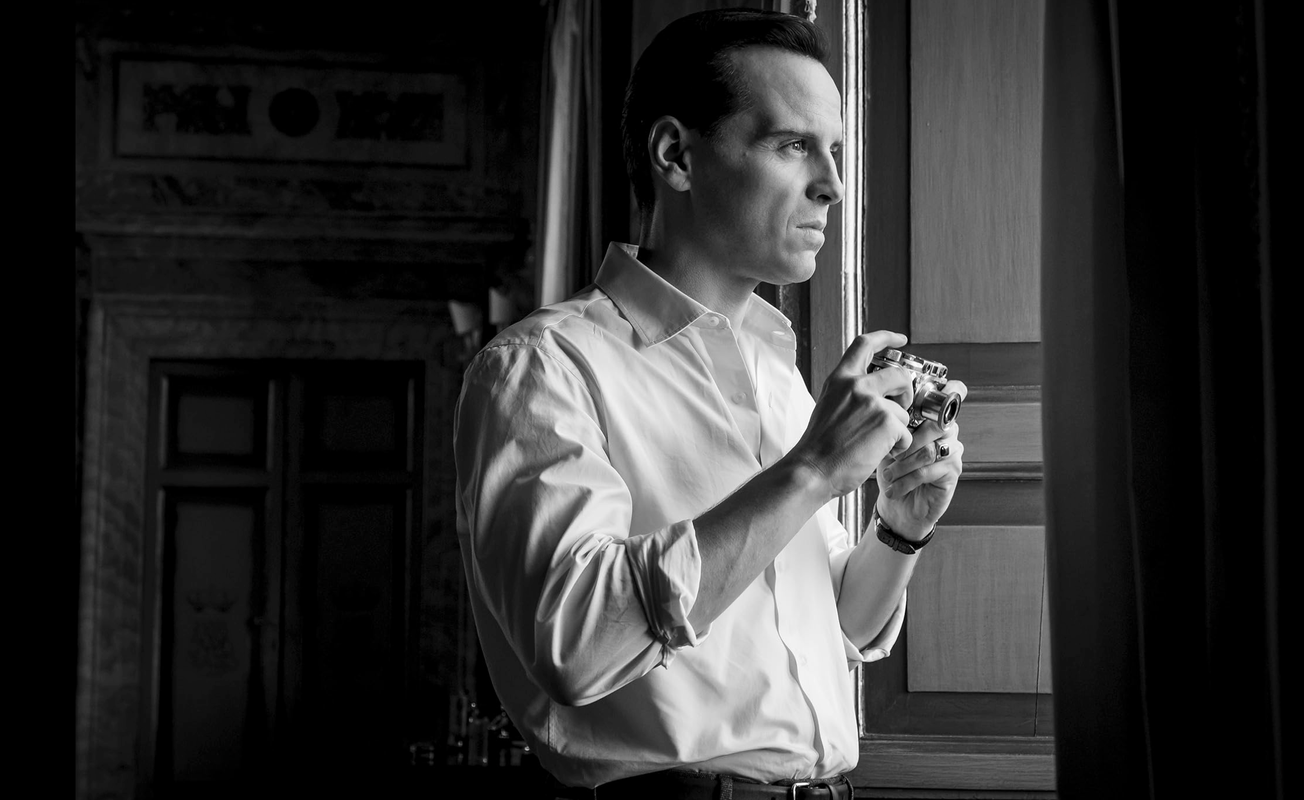

Featured Image: IMDb / Edge of Tomorrow / Warner Bros. Pictures

Are strong female characters neglecting all aspects of feminism in the majority of mainstream films?

Facebook // Epigram Film & TV // Twitter