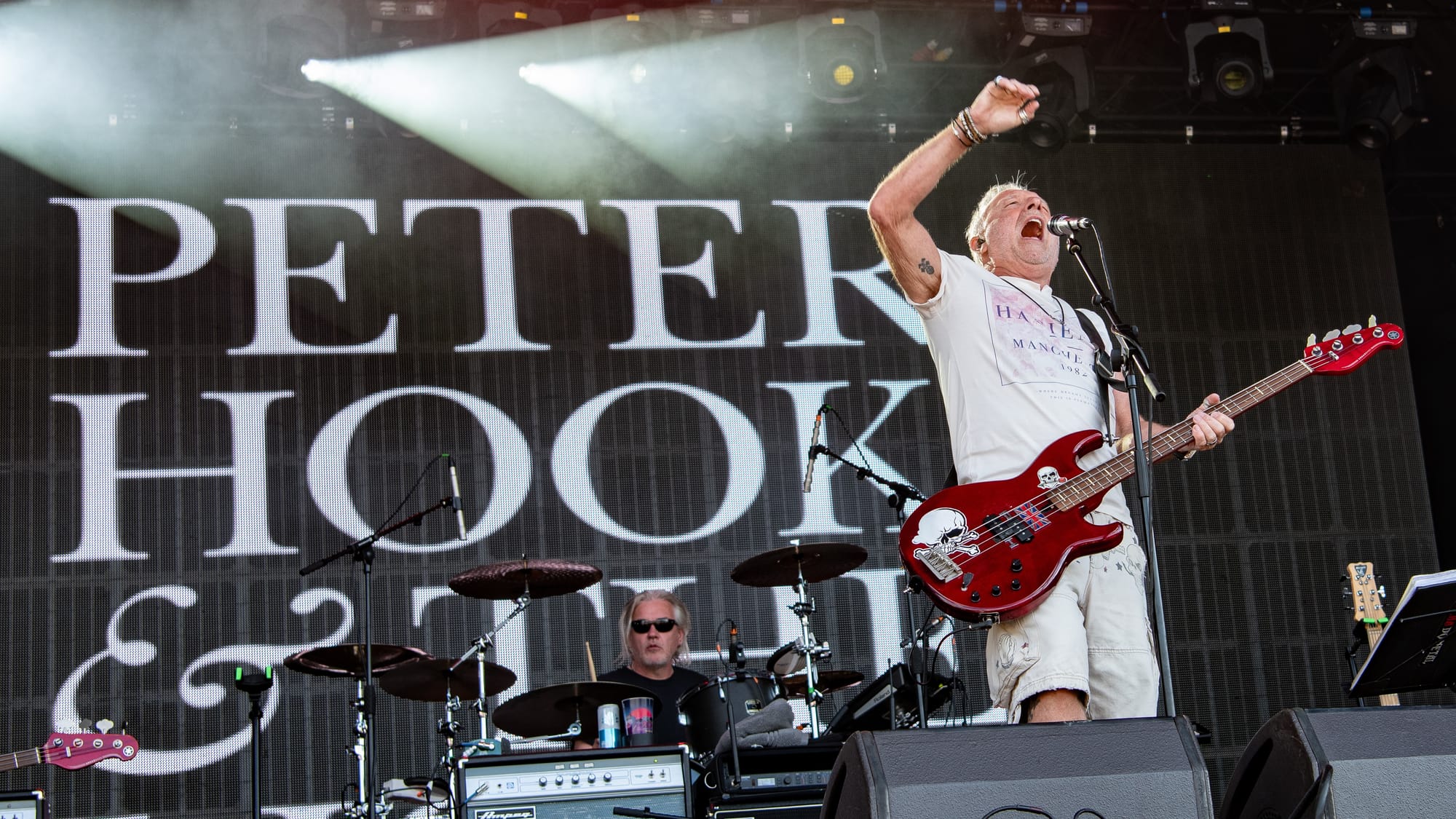

By Benji Chapman, Co-Deputy Music Editor

Trigger Warning: This article contains mentions of suicide

Peter Hook began his musical career as Joy Division's bassist: a twenty-year-old punk rocker who didn’t know his amps from his speakers, or bass from electric guitar. With the tragic passing of lead singer Ian Curtis, he went on to found New Order and fronted the spearhead for a more danceable period of British music. We sat down to talk bands, mental health, and most importantly, Mancunian Uber drivers.

Manchester is one of the few constant backdrops to Peter Hook's impressively diverse musical career. As we discussed, it's a mysterious place; instilling a 'Manchester attitude' into its citizens that is supposedly funnelled into its short-tempered Uber drivers, leading Hook to abandon any use of the app altogether. 'You should do what I do, don't use them', he cracks with a grin as we start our conversation.

He's done far more than catch cabs in the city though, co-founding the city’s famous Haçienda nightclub alongside New Order and Factory Records in 1980 after his time in Joy Division concluded. He would later witness an unfortunate closure for the venue seventeen years down the tracks: ‘The architect was given a blank cheque to create whatever he wanted, and we didn’t know.’

‘The next thing we knew we were 750 thousand quid down, with this huge, over-designed club that basically nobody wanted to come to for a long time.’ The ‘blank cheque’ that the Haçienda team possessed also set the precedent for some interesting bar selections; selling only Red Stripe lager at manager Rob Gretton’s behest, before switching to his new favourite beer, the costly Sapporo lager, upon its discover in Japan. ‘How bonkers is that!’ Hook chuckles.

Noticing my IDLES t-shirt that’s beaming through our zoom call, he observes just how unthinkable the nightclub's creation would be nowadays. ‘What impresses me about bands these days like the bands you’ve got on there, IDLES, is that they have to be in charge of everything… I think that’s better. But what you don’t have now is a huge record industry the way we [New Order] had.’

As the onus of responsibility to finance, produce material, and promote a band falls more and more onto the members themselves, he comments ‘IDLES will not be able to open a club - I can guarantee you - or be able to entertain a city for seventeen years the way New Order did, with cheap drinks.’ With a second cackle, there’s a distant twinkle in his eye that’s sparkling with recollected fondness of what I imagine were some duly hedonistic nights that trickled into the early morning, during the glory days of the ‘Madchester’ scene.

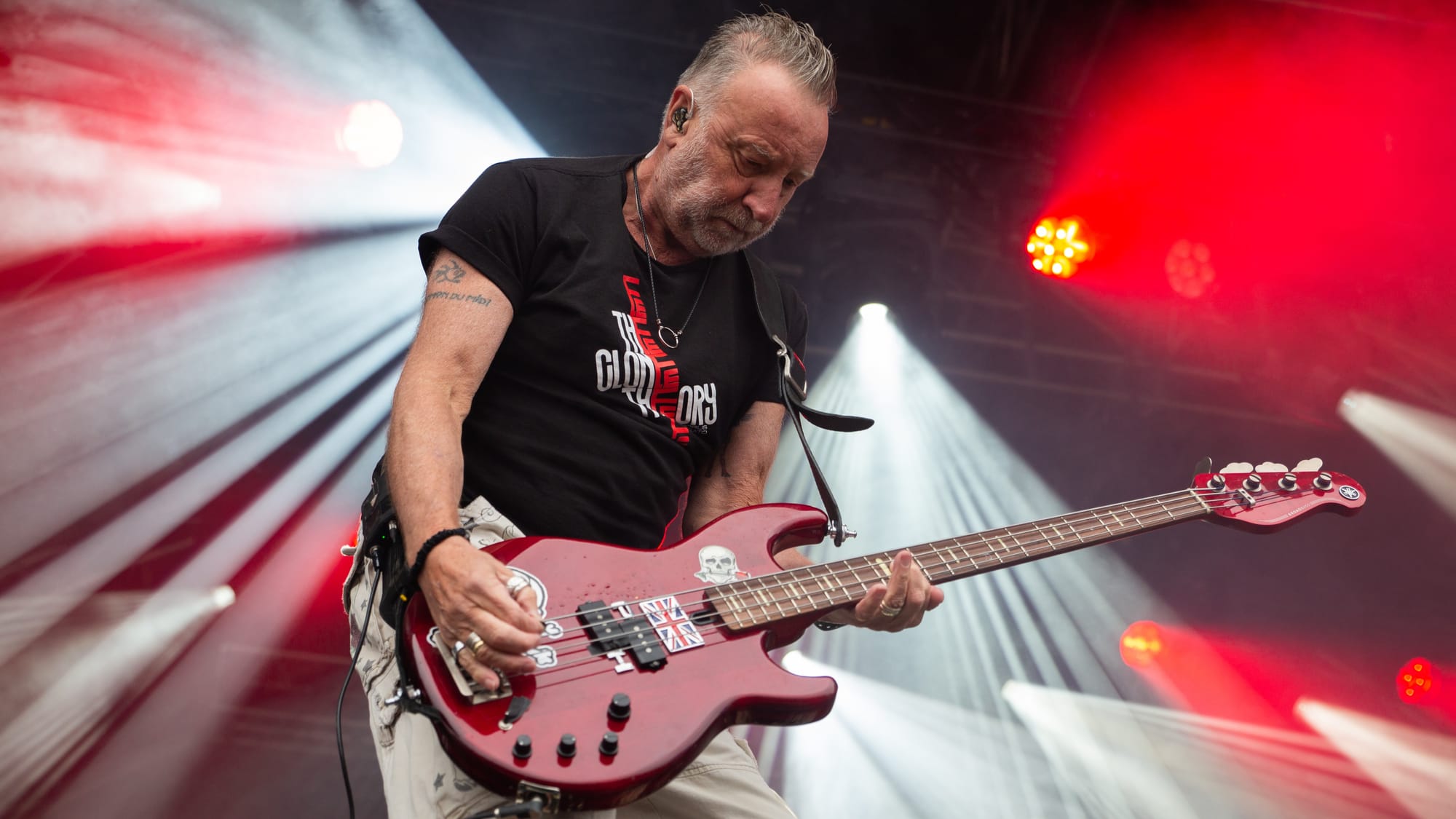

Something of a chronicler for the UK’s ever-changing music scene, Hook witnessed and participated in the popular transition from punk-rock to dance music. His time in New Order in the ‘90s is sonically bright and polished whilst his start in the punk scene of the late '70s bears a grittier, DIY attitude. He explains by starting with the story of when he bought his first ever bass guitar.

‘That’s only got four strings, my mate’s has got six strings’ Hook recalls telling the shop’s owner, who replied, ‘”that’s cos your mate’s is a guitar, knobhead: this is a bass.”’ As we briefly geek out about music gear, he also tells me how he was forced to use a shoddy £10 speaker that was purchased after mistakenly buying an amplifier with no speaker cab.

This forced Hook to play unconventionally high-pitched melodies at the top end of the instrument's neck, since the cheap speaker he bought couldn’t articulate any lower-end bass frequencies. ‘It sounded like ten quid’ he grimaces in recollection, though Joy Division was apparently not a project that began with money – or an awareness of much at all – in mind, as Hook details.

‘We were your age (twenty) when we made that record [Unknown Pleasures], and I don’t know about you, but we didn’t know our arse from our elbow.’ As I jokingly check where my elbow is resting, there’s a mutual understanding in the call that the age is not necessarily one when you write the one of the most seminal post-punk records of all time.

But the sweet irony of the band’s success was their own inability to see any capacity to produce such a revolution in the scene. ‘We were writing music that we couldn’t tell how good it was... We wanted Unknown Pleasures to sound like the Sex Pistols’ Nevermind the Bollocks: big guitar, rip your head off. Total punk. We wanted a punk LP.’

‘Martin Hannett realised that our songwriting had far outstripped our mental capacity’, Hook laughs fondly. ‘That’s how daft we were. We were just kids messing about… and I must admit, when he gave us Unknown Pleasures, we were going “what the f*ck is this? This doesn’t sound like the Sex Pistols?”’

The trade-off for the initially disgruntled band, however, was that they could revisit their more angsty sound live, whilst producer Martin Hannett sealed the slower and more ambient aspects into the studio album. ‘Live we were a lot different, we were very aggressive’. Hook smirks, saying, ‘We got the best of both worlds. He gave us a great record that had the wonderful gift of timelessness: the reason you’re listening to it years later is because of Martin Hannett’s production.’

‘If me and Barney were let loose, I probably wouldn’t be sat here talking to you’, he ends with a shrug. Channelling the young members’ enthusiasm was clearly no easy feat, as Hook imitates his twenty-year-old self grabbing aimlessly at the air. ‘In those days, you had to seize the moment – you were a kid! What do people say to you nowadays? “Don’t rush, take your time”, and you go “no! no! I want it now!”’

We discuss how a feeling of needing to seize the moment at the time perhaps inadvertently contributed to the devastating end of the band. When lead singer Ian Curtis took his own life in 1980, Hook describes how ‘He was suffering from something that he needed to correct, but he didn’t understand it… He didn’t want to lose the impetus, so he forced himself on as well as he could, and in the end, he decided that - for many reasons - he couldn’t carry on.’

After Isaac Wood’s departure from British post-punk outfit Black Country, New Road in 2022, in order to address his mental health, I presented this to Hook as a point of reference for how the music industry - and maybe society more broadly - has potentially strengthened its education around mental health.

‘It’s better now, and I’m better educated. If I had had the education I’ve got now, then I wouldn’t have let him play', Hook says in response. ‘I would have took him home and I would have sat on him until he got better.’ Recalling a gig in Bournemouth where he held Curtis’ tongue for over an hour during a seizure, the extent to which Curtis underemphasised his struggle could not have been made clearer by Hook.

‘We took him to the hospital, and he came out of the hospital and said “right are we going for a drink?” and we’re going “Ian, you’ve just been on the floor for an hour.” Could we stop him? No.’ Its touching how Hook so vividly recalls his time in Joy Division, even with the passing of Curtis, who was so central to the band- the first to instruct Hook to play so high up the neck of his bass. 'Really it was at his behest’ he says. ‘I still feel guilty about Ian now, the same way I feel about a lot of my friends who have passed away.’

Yet, if the departure of Isaac Wood from his band has signalled anything, it’s that there is a newfound - and growing - awareness within the British musical community concerning the extent of the pressure applied to musicians, and more than this, an acceptance of the fact that taking time off is ok.

We’re not afraid, I’m not afraid, to say “I can’t do that”’ Hook tells me. Speaking to me directly he says, ‘You should always look after yourself, I’ve learnt, because the world keeps turning. You just get back on six months later.’

Far more than an interview, my conversation with Peter Hook was an unexpected lesson in navigating your twenties; from not jumping to buy the first piece of kit that catches your eye in a music shop, to being paramountly aware that taking time out is not akin to your life plans shuddering to a sudden halt.

In a meaningful fashion, the words of Hook are evidence that rest and rehabilitation come first in the approach to wellbeing and mental health. We can't wait to see what is next from a man who has massively helped change both the sound and spirit of the British music industry, as he begins a 2024 tour with his new band The Light, before coming to Bristol to play Marble Factory in April 2025.

Featured Image: Ivan KarczewskiWhat is your favourite Hooky bassline?