Jacob Rose, Third Year, Film and English Literature

Having the delight of watching The Old Oak, Ken Loach’s (at least self-declared) last film, at the cinema, was something I only felt the true power of during. As an experience, it captured something intensely fantastic about the near 60-year run in which Ken Loach has been directing films - the immensely important way in which social realist films like The Old Oak deliver a message of social change, and of the struggle to do so.

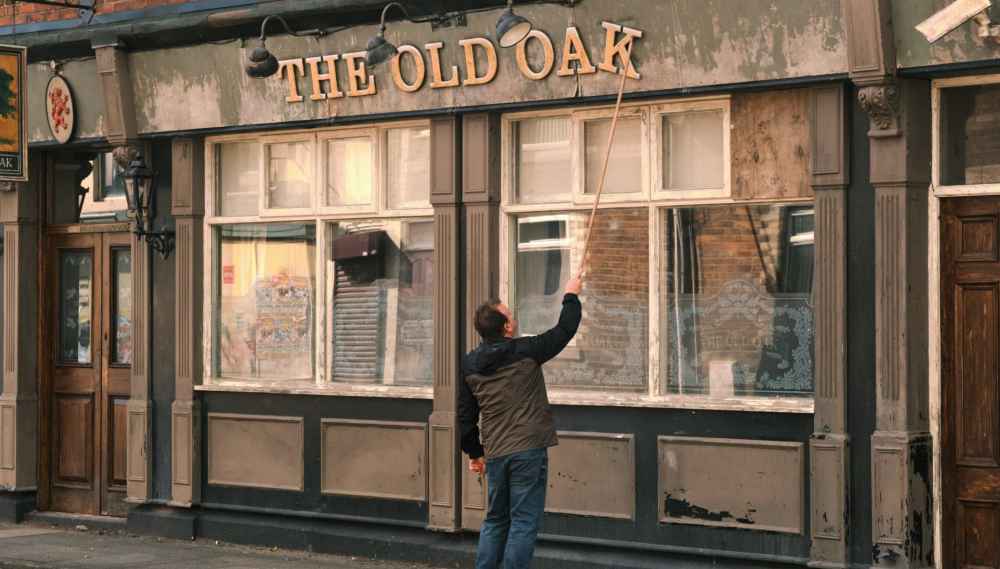

The Old Oak itself follows the dual experiences of Tommy Joe Ballantyne (Dave Turner), a pub owner helping to rehouse Syrian families within his village, and Yara (Ebla Mari), one of the Syrian refugees who helps to inspire the integration of these families into the ex-mining town’s community. Set in 2016, tensions are high, and the usual direct, crude (not necessarily a negative) method of storytelling in films directed by Loach takes the audience through a tour-de-force of struggle and fighting.

It is a fight against inaction. Against not just the ‘usual racists’ (fans of the phrase “Go Back To Your Own Country” will be cheering in their seats) but those like TJ - those who allow a stagnation, willing to help but only in ways that don’t challenge any existing structures. A notion rings (originating from the racists, mind you) that in helping these families integrate, he will be neglecting the ‘locals’ - this fight to re-realise what unionisation means for a festering, damaged mining community is tough, but salient - our protagonists struggles pervade beyond the narrative on display, prioritising realism over narrative convenience.

Yara’s role, following suit, occasionally strays into territories that also feel slightly conventional. A voice of the refugee collective, Yara’s perspective is the first we see - through photographs she takes, beautiful still-life compositions, jarring against the comments of ‘suspicious’ peering locals.

While we occasionally dip back into her perspective, both behind the camera (a slideshow sequence later into the film, where the mining community views themselves through Yara’s lens, brought me to tears) and in the home, this still feels like a film concretely For a British audience. Yara’s determination, kindness and occasional acceptance of people’s bad sides (some of the town’s racism feels simply solved by her kindness, instead of internally challenged) limits her personal characterisation.

The few scenes we do get inside the home evoke some strong reflections on the separation from home and the desensitised, unexpected emotions that follow, flashing signs of development that help keep their lives as lives instead of merely symbols. In stressing the focus towards a British audience, it leaves an opportunity for more to be told from this external perspective.

While un-subtle, The Old Oak speaks an important message, and one that works. Stories from Loach about the creation help to remind us of the importance of these actors (as usual, they have really lived the bulk of the experiences they perform) and of creating a film that accommodates their desires as people. It is a film that speaks as it does, creating a unity between performance and production that inspires audiences to follow suit. Despite its tendencies towards conventional storytelling, that unity holds The Old Oak united, as a marker of what must, and hopefully will, happen in the future of filmmaking.

Featured Image: IMDb