By Milan Perera, Arts Critic Columnist

Over the last few months Epigram arts writers have had the opportunity to review some of the finest productions of musicals and operas created by fellow University of Bristol students, including a stirring rendition of Gypsy. Behind the soaring music that propels the drama forward, there is one individual who dictates terms on the orchestral sound that fills the theatre: the conductor.

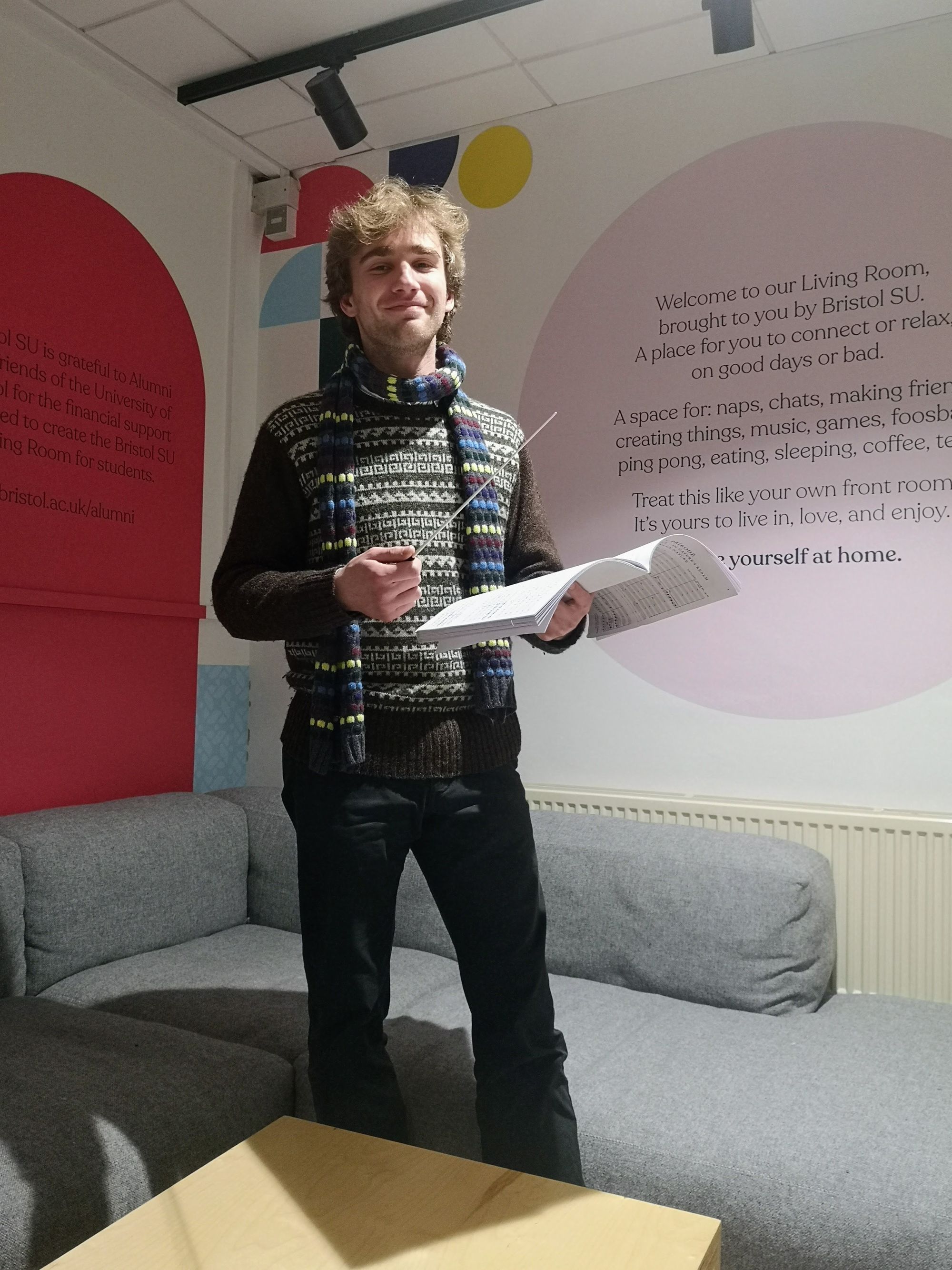

When I went to see Gypsy at the Winston Theatre in early February, I made sure to sit at the right-hand corner of the front row to catch a glimpse of the orchestral pit underneath the stage. I could not help but marvel how a downbeat from the baton held by Madeleine Warren prompted a mesmerising sonic cascade that began to fill the theatre. It was as if the downbeat caused a spark of electricity. She brought various sections of the orchestra on cue and gave instructions on the texture, tempo and the dynamics of the sound with hand movements and facial expressions. I found the whole spectacle fascinating.

How is it possible that the only person who is not playing an instrument has the biggest say on the texture of the sound? From a distance it was as if some mysterious powers were trapped between the palms of the conductor.

On the back of the soaring success of Tar, starring Cate Blanchett, there was a renewed interest in conducting. To unravel and unpick the art of conducting, Epigram had the great privilege of interviewing conductor and composer David Simkins who has been the driving force behind some of the biggest university musical productions.

‘Conducting is communicating’ summed up Simkins. The sound of an orchestra even under the same conductor is never static. ‘The orchestral sound is temporal. It cannot be repeated’, Simkins continues. Even with the same orchestral piece, with the same orchestra, under the baton of the same conductor, the sound has a unique sonic imprint each time.

He elaborated this point by recounting one of his recent experiences. In preparation for a tour in Germany, the Bristol Symphonia rehearsed at St. George off Park Street, but when they played in a hall in Germany, the texture sounded completely different, although they practiced it to a tee. In his opinion the acoustics of the building and the architecture play a crucial role in the projection of the sound. And this is where the conductor steps in.

I put to him bluntly, ‘what exactly does a conductor do?’ ‘A conductor is an interpreter. In front of him are roughly one hundred highly talented musicians who know their parts. The conductor’s duty is to construct a composition in stages, like a painting, with the help of those musicians’.

According to Simkins, the conductor is there to guide the group of musicians with the aesthetic ideas formed by the conductor regarding the particular composition. The conductor has a duty to the original composer and approach it with empathy, without self-indulgence. Contemporary composers tend to be more direct and detailed in their directions on how they wish their music to be played, especially regarding the tempo (clearly marked with beats per minutes), marked on top of the score and dynamics such as allegro(fast) or pianissimo(soft). But even so, there is the necessity of needing someone to have the final say in how these dynamics should be executed.

For example, a passage that is gaining intensity (crescendo) has to be conducted. With hand movements and facial expressions from the conductor these bits of information are conveyed to the musicians.

I then asked Simkins to demonstrate how to convey softer sound (pianissimo) and how to create a crescendo. He obliged and kept his hands close to his body and his wrist firm, whilst moving the tip of the baton in smaller movements. When he wanted to create a gradation of increasing sound his hands moved away from the body and the shapes he drew in the air with the tip of the baton bigger.

Simkins jokingly referred to the baton a ‘magic wand’ as in Harry Potter. He instructed me that an orchestral sound always begins with a downbeat – a downward movement of the baton and the bar finishes on an upbeat.

The function of the left hand is to provide a cue for an entry for a soloist or a section (for example second violins). With a raise of an eye brow or a nod, so many nuanced musical instructions could be relayed.

Simkins reiterated that it is not just flawless mastery of technique but creating moments which are profoundly human. Music is beyond dots on a piece of paper, capturing the cornucopia of human emotions from elation, joy, resentment, sorrow to magnanimity.

The word he kept returning to was ‘empathy’, which according to him is of paramount importance, not only to the composer but the audience, who are an integral part of the experience.

This mystery may have been used and abused by some conductors who project a cold, distant and god-like persona. But he is of the opinion that conducting has moved from the days of ‘autocrats’, who more often than not built a wall between the orchestra and the audience.

In concerts, Simkins makes sure to turn around to the audience and provide some context to the individual piece or the programme. He pointed out that the post-lockdown period marked a sharp drop in concert attendance, which forms a part of his research thesis for his Masters degree in Music and Innovation.

With regard to compiling a programme for a concert, he points out that sometimes the conductors have to be creative in order to entice the audiences, mixing crowd pleasers with less familiar pieces, whether it is a number from the Lion King or a movement from the Eroica symphony.

The scholarship surrounding the understanding of music has developed in leaps and bounds; Simkins explained the ‘shapes’ of different emotions in a standard piece of music. Noticing the quizzical look on my face he explained that it is described in great detail by Manfred Clyme in his book, ‘Sentics’. He drew a graph on a piece of paper and explained its curve, where it starts on a higher coordinate but drops drastically to almost the horizontal axis, but just before the end of it gains a slight spike, ending on an optimistic note.

Simkins reiterates that it is not a requirement to be a master of an instrument in order to take up the baton, although there are those conductors such as Daniel Barenboim or Vladimir Ashkenazy who were fully fledged soloists before embarking on conducting.

‘If you have a passion for music, if you are able to communicate the emotions embedded in those pieces of music, if you have empathy and something in your mind, you can make music, even without a great technique.’

David Simkins has a mission; this mission is nothing less than bringing the transformative power of music to audiences and connecting with individuals. It is no doubt that his parallel career as a composer provides him with a unique perspective on how compositions are layered.

Featured Image: Courtesy of David Simkins

How much did you know about conducting and composing?