By Ursula Glendinning, Wellbeing Deputy Editor

Croft Magazine // Ursula Glendinning, our Wellbeing Deputy Editor, talks us through her recent love of running. And how this new hobby has changed her relationship with nature.

Earlier this year, I took up running again. Setting off through Bristol, I went through the ever-familiar early stages of a run. First, a wall of cold air, through which I aimed to emerge; if I continued for just a little further, I might meet a warm spring breeze. Then, a (probably deluded) confidence in my ability to maintain the speed at which I had begun. Clifton was flying by until, a couple of minutes in, it wasn’t. God, I wish I could just get to the end of this road. I thought of the checkpoint I could begin walking at. It was a familiar sequence of feelings and ones I had grown accustomed to over the summer of 2020.

Every day, from mid-March to September of 2020, I ran along the country road I had grown up on, and then circled back over the moorland. I was startled by the heavy silence that had descended since the world came to a standstill. It was periodically broken by one or two cars. Frequently, bird songs reverberated through the valley, chorusing with the trains. The duo-tonal great tit and songful blackbird overtook sonorous political babble from the radio. Although my road had never previously been susceptible to heavy traffic, I had been warned away from it as a child, for people travelled along it fairly frequently and often at a dangerous speed. But during the pandemic, the volume of cars slowed down to a trickle, and we were engulfed in a country calm we hadn’t experienced for years. For the first time, I was able to run on the road without fear of a misstep leading me into the path of an oncoming vehicle.

The moorland also became somewhat transformed by the international standstill. My headphones came off, and I was alert. A pheasant, disturbed by my heavy foot fall, launched itself from thickets, unapologetic in its voice. The heather was a royal purple in the spring. Sometimes it was raining. The catch, which ran alongside the path, was thick with reeds and frogspawn. I can remember long expeditions through these streams as a child, pretending I was braving a river, up to my waist in cold, perishing water. In reality, the stream was slow and sometimes dried up. There were some days when I needn’t have even taken off my boots to wade through it. The banks rose in flanks around my head; all that I could see was the stream ahead and the fern that unfurled, emerald and startling.

When traversing my home valley, an acquired myopia is necessary. It is easy to become overwhelmed by the scale of the hills and the quaint imagery of abandoned farmhouses slumbering against giant inclines. One’s ambition is at risk of being overcome with the prospect of reaching precipices over which one might suddenly find an epiphany. This will presumably happen by seeing the toy houses of the local village and people paragliding off the cliffs of the Peak District. But it was through noticing the finer things, the things that I could put a name to, that made me truly feel part of something bigger than just myself. The fairness of mortality or mastery over what is inevitable never crossed my mind when I realised there was something reciprocal accessible here.

My runs became a source of solace, and when I look back on that summer, I remember running above everything. Maybe because of the intense physicality of the activity, in that moment, I was grounded. It’s harder to remember the other things: waiting, hospitals, the news. My liminal existence was briefly but wonderfully interrupted by heather. I would stop for bilberries along the way and stand still for twenty minutes with my hands shading my eyes, watching as a buzzard circled up ahead. It hurt; I felt aches deep in my calves and developed stitches from eating handfuls of raisins beforehand. But I wasn’t thinking about anything else. The grief I held in my hands was, in that moment, walking alongside me with the earth. With each step I left a small part of that heaviness on the path.

In retrospect, running 5km a day was gruelling, punishing even. Now, I run every couple of days, and rarely over 3km. Although this certainly will not leave a particularly strong impression of my athleticism on my reader, I want to highlight that connections don’t need to be assumed in extremes. In those moments where I was running, or even dragging myself along, barely walking, I was - and am - present. Contrary to the idea that nature was a place of isolation and escape, in those days I was coming to myself, away from whatever craze was sweeping the internet. These moments were not of flight but rather instances of being brought back to the earth; instances of embodiment.

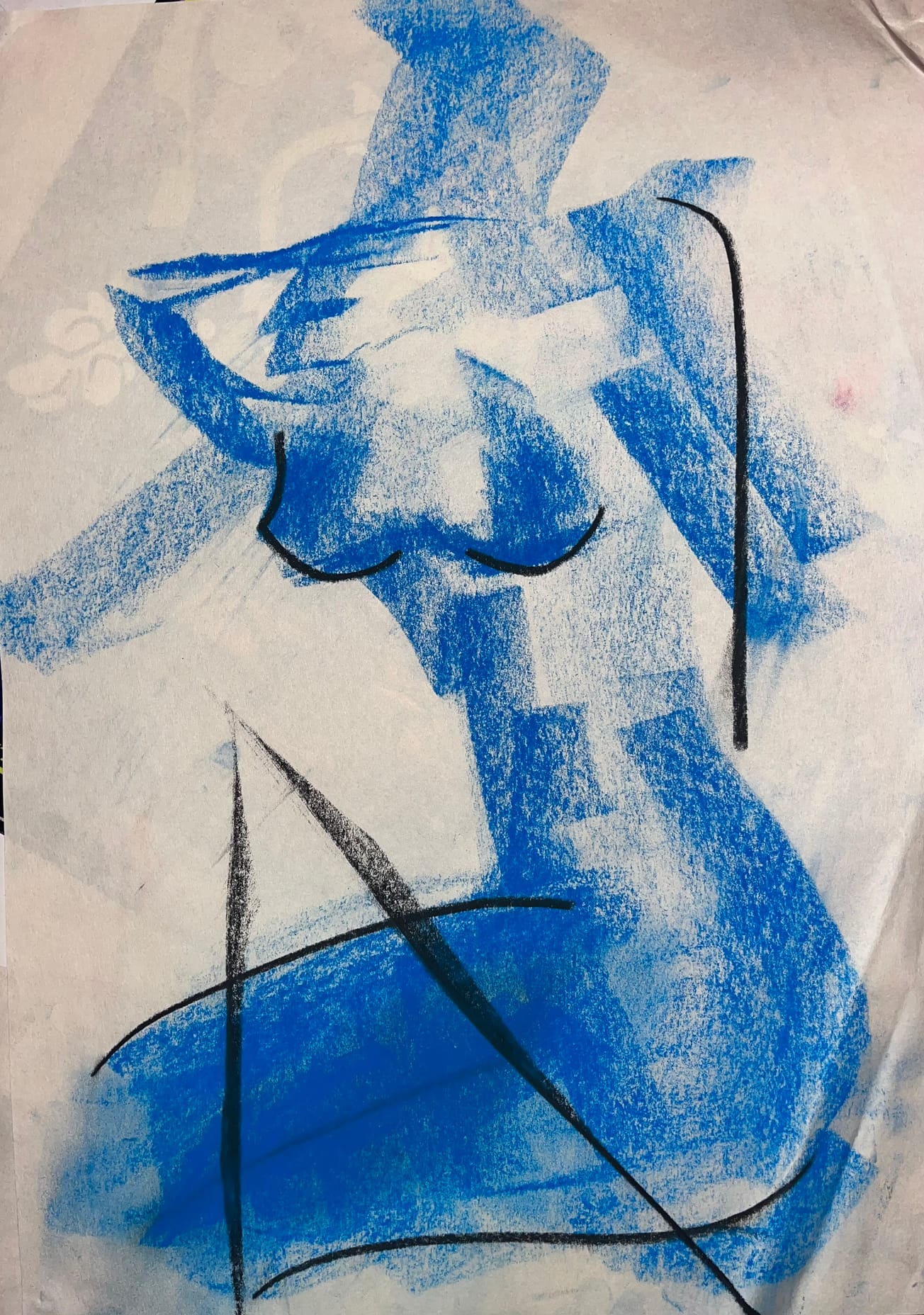

Featured Image: Emily Fromant