By Leah Martindale, Film and TV Editor

With films like Black Panther (2018) and Get Out (2017) showcasing the huge wealth of black talent in cinema, it can be easy to overlook those, such as Oscar Micheaux, who went before and made this possible.

Amongst a growing band of contemporary black filmmakers, actors, sports stars, and celebrities, and trends like #OscarsSoWhite permeating the internet, it could be easy to mistakenly think that black involvement in cinema is a recent phenomenon. While it is undoubtedly true that there has recently been an exponential boom in black cinematic representation, it would be a crime to forget cinema’s forefathers this Black History Month.

As the fifth of thirteen children born to a freed slave in Illinois, Oscar Micheaux was dealt a difficult card when he was born in 1884. Despite this, he managed to make history as the first African-American producer of a feature film as shockingly early as 1919. As a writer, performer, director, and producer, Micheaux was a trailblazer in the black filmmaking milieu and the history of film more broadly.

Michaeux’s death of heart disease in 1951 preceded the American Civil Rights Movement by approximately three years, by which time he had managed to amass 39 writing, 42 directoral, and 38 producing credits. At just 17, he moved cross-country, and within a few years became a homeowner in South Dakota, where his ‘blue collar’ white neighbours inspired his early screenplays.

Micheaux’s films were by black filmmakers for black audiences, a rarity in early cinema

His first book, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Homesteader, sold over 1000 copies. While that was published anonymously, his later novels were published under his own name, and his novel Homesteader inspired his 1919 feature The Homesteader. After raising the money to produce the film by selling stock to white businesspeople, the film was put into production, forever changing the landscape of cinema.

As a forerunner of the ‘race film’ genre, Micheaux’s films were by black filmmakers for black audiences, a rarity in early cinema. ‘Race films’ gave light to actors otherwise sidelined by the racist stereotypes of cinema many of which are unfortunately still partly present today.

The first black performer to win an Academy Award, Hattie McDaniel as Mammy in Gone With the Wind (1939), serves as a bittersweet example of the roles black performers were typically afforded - while she received arguably the highest filmic accolade achievable, it was as a one-dimensional character in a piece with undeniably racist confederate roots.

There are so many to celebrate (don’t worry, the influx is coming) but today I wanted to talk about one of the pioneers of black cinema - Oscar Micheaux - and the influence he’s had on the craft since the very beginning. We salute you, Oscar M. ✊🏾 #blackhistorymonth pic.twitter.com/pdpnZSzlp7

— Strong Black Lead (@strongblacklead) February 4, 2019

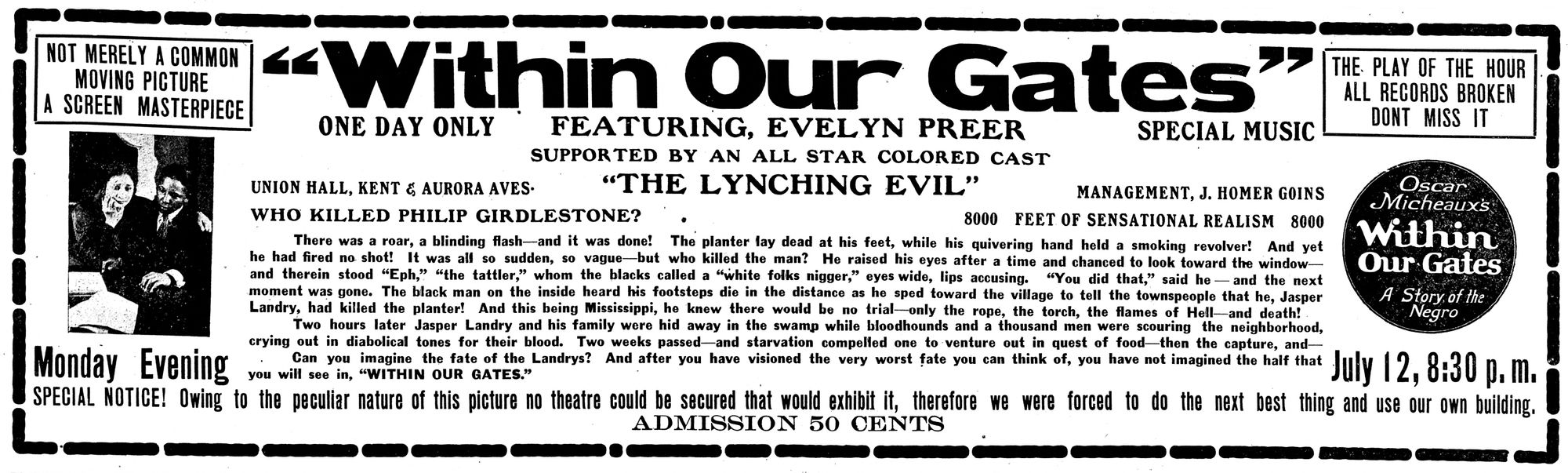

Micheaux notoriously produced Within Our Gates (1920), a film acting in response to the 1915 cinematic glorification of the Klu Klux Klan, The Birth of a Nation. The bravery it took to openly criticise the racist structures that infiltrated his neighbours, police officers, law-makers, and peers alike is impossible to comprehend in today’s society.

With Jim Crow era lynchings declining in popularity mere months before the film’s release, Within Our Gates was not just a political statement, it was a matter of life-or-death.

Micheaux’s life is an example of the lost history of black and African-American cinema. With an estimated over 400 race films lost to history, technology, and undoubtedly racism, his longevity as an artist is a testimony to his pieces’ exceptionally wide reach, interest, and historical importance.

Within Our Gates was not just a political statement, it was a matter of life-or-death

Despite being criticised by journalist Richard Gehr as having ‘only one story to tell, his own, and he tells it repeatedly.’, Micheaux’s historical longevity versus Gehr’s descent into insignificance proves that one story was wholly more worth telling.

Micheaux’s legacy has only grown posthumously. As well as receiving awards from organisations ranging from the Hollywood Walk of Fame to the Directors Guild of America, the Micheaux award has been created by the Producers Guild Hall of Fame, and he has even had film festivals curated in his name.

While Micheaux described his films as ‘narrow at times’, history has remembered them as anything but.

Postal stamps bearing his image, positionings on lists of the 100 Greatest African Americans, and even a documentary on his life have been created: while Micheaux described his films as ‘narrow at times’, history has remembered them as anything but.

Micheaux’s extensive career and life-and-death dedication to his craft affords him a position in all of our Black History Month remembrances. The pioneers of our wonderful craft faced issues with technology, distribution, and development - add in racial discrimination as a factor and the feat he acheieved seems near impossible. And yet, Micheaux persevered - and for this, he can be called nothing other than an icon.

This article is part of Epigram Film & TV’s Black History Month coverage. Over the course of the month, we will be featuring stories of pioneering black figures in cinema and highlighting some must-watch pieces of black cinema.

Featured image:Library of Congress / Micheaux Book and Film Company

Are there any other pioneering black filmmakers that stand out to you?