By Juniper Gardner, Second Year Philosophy and Politics

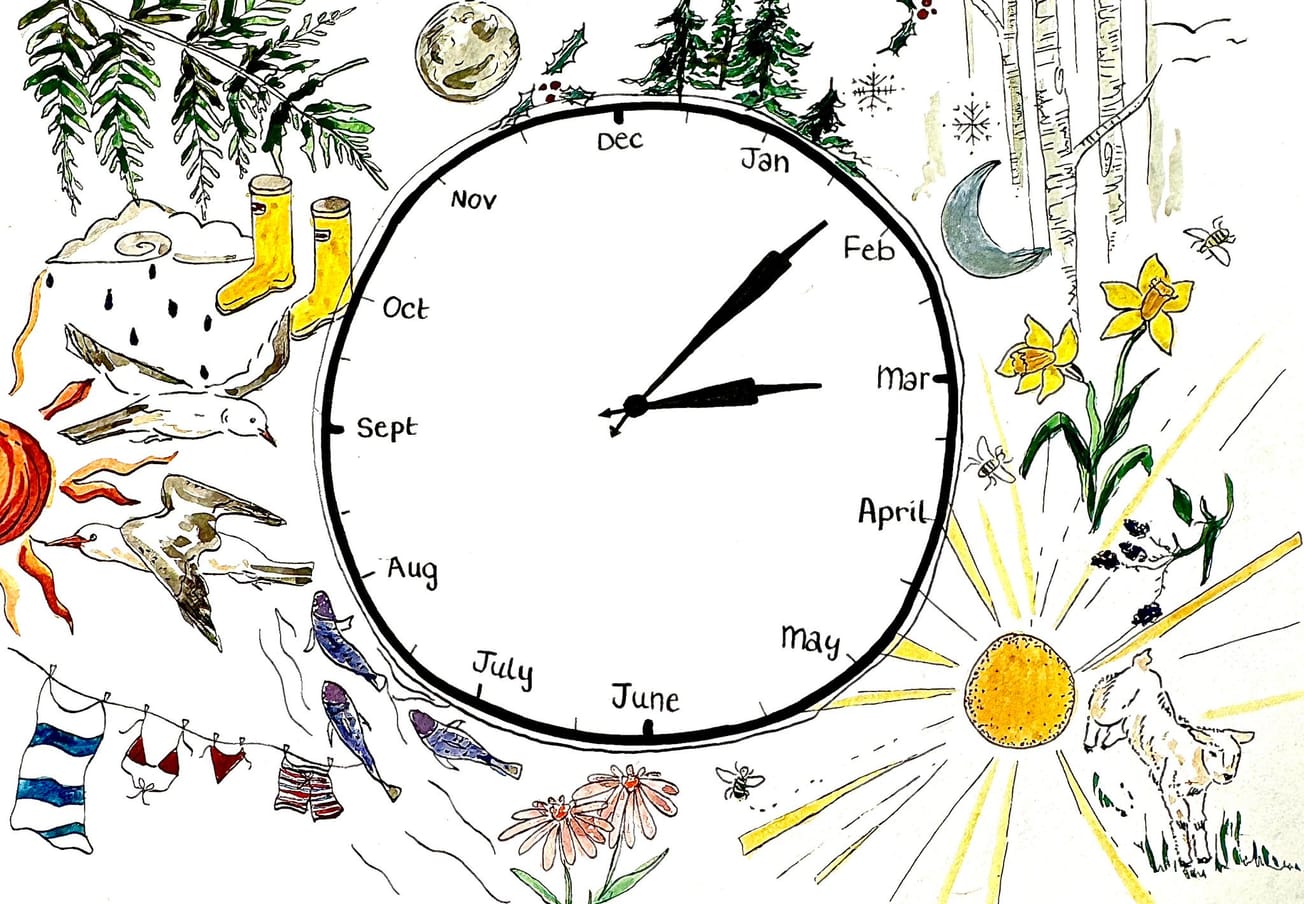

Catching up with loved ones is always important when taking a break from the stress of university. However, there seems to be one exchange I have with any given relative at least a handful of times every time I go back home, a conversation that haunts every non-STEM student just trying to enjoy the break from their studies.

‘Oh, you’re studying X? What job can you actually get with that?’

Less of an actual question, more of a cautionary reminder: ‘you do realise what you are doing, don’t you?’ is what they’re really getting at, disguised with feigned interest and curiosity. This is, of course, followed by a rush of anecdotes about their own children’s university careers, and how they are so unbelievably proud that they chose to pursue Law, or Medicine. Without saying it outright, how relieved they are that they chose a real degree. If the current job market doesn’t already keep you up at night, now you know that your aunts and uncles are just as unsure about your career prospects as you are.

This is, of course, untrue. Someone’s pursuit of a University education in English or Fine Art should hold as much value as if they were studying Medicine or Law. Why, then, does this feel controversial to say? Some may retort that lawyers and GPs make a much more tangible impact on the world around them, which leads to a bigger issue: what does it mean that the degrees mentioned in the former, ones seen as not having a real-world impact, are also ones that are female-dominated?

As termed by Margaret Hodge, what happens when these ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees and the low-level employment they are seen to result in targets a massive percentage of female graduates? Are current views on humanities-based degrees burying a shallow grave for women after university education?

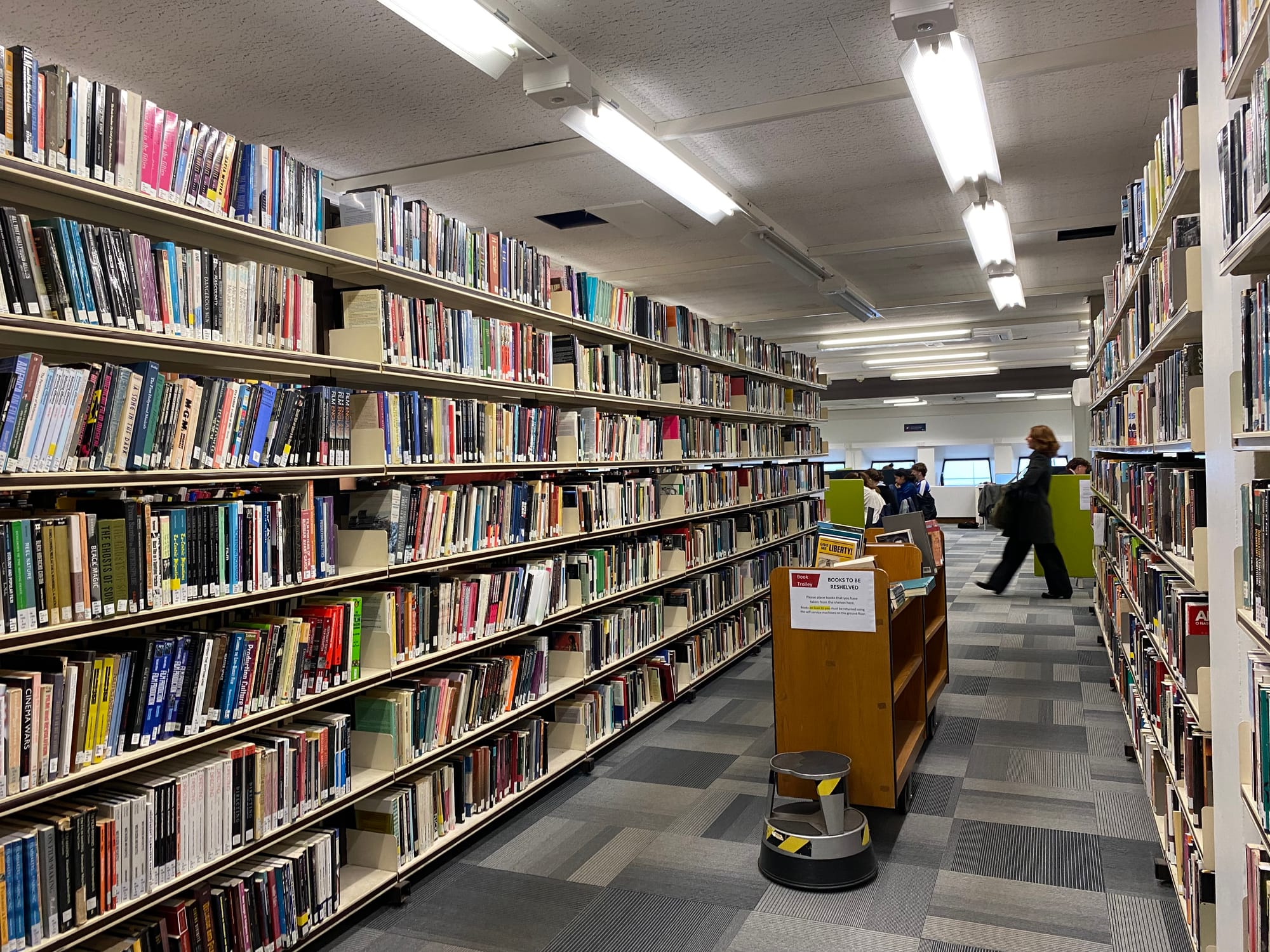

What led us to believe that a degree in the arts or humanities inherently held less worth in the first place? What has tricked us into thinking that there is something unprofessional about, say, someone devoting themselves to the study of film, one of the most documented forms of emotive human expression? Why do we not recognise the intelligence of someone studying anthropology, who has their finger on the pulse of the human experience? When all of these fields are discarded as useless, what is left for the women of the arts?

‘We can respect the choices of these people retroactively, after their success is proven’

Firstly, it's important to recognise that success has never truly been unreachable for those with non-STEM degrees. Fashion icon Vera Wang, who graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in 1971 with an Art History degree, found immense success when her groundbreaking approach to wedding gowns transformed bridal fashion forever. Before becoming the powerhouse actress we know her to be today, Meryl Streep studied Drama at Yale. Martin Scorsese studied English before his work broke out into cinemas around the world. You would be hard-pressed to find someone willing to chastise these titans of their fields for their choice of degree. What, then, makes their choices, but not ours, respectable? There is an unfortunate answer to this question, which comes in the form of an understanding that we can respect the choices of these people retroactively, after their success is proven. This respect is seldom extended to current cohorts of undergraduate students. This is worsened further by AI’s steamrolling of tasks in creative industries, furthering the idea that we as humans are better than engaging in menial creative activities. The writer and artist are being displaced by the machine and the manufacturer. This poses a great worry for the future of the women of these industries, who make up the majority of students across these degree subjects. What is worse, this struggle is not a new phenomenon.

Pam Skelton, in her article ‘Women in Art Education’ (1986), surveyed female art students about their overall thoughts and feelings about their current education in the arts. She identifies the product of complex discrimination of female students as the ‘confidence crisis’, which keeps women from thriving within creative spaces, despite having a higher education in creative subjects, due to feeling like they are unable to achieve that success. This documented subduing of female creativity through rigorous criticism is something that may resound with many today, with no real solution in sight.

‘The value of a degree in the arts [...] is found in conversation with others, in creation, in debate’

Coming back to university after visiting home, there is a significant bruise to your confidence that you carry when you’re a woman with a ‘useless’ degree. You don’t want all of this to be for nothing, but this is hard to honour when you are unsure if what you are doing is anything at all. This philosophy, though temptingly defeatist, is quelled quickly when you surround yourself with women in the same boat as you. The conversations I had back home are forgotten quickly when re-entering the uni bubble. Before I have even dropped my bags off in my room, I am bombarded with the unbridled joy of my female flatmates gushing over a new piece of media they had the chance to produce as a part of their film module, or brooding over a written classic they’ve had to analyse for English. You start to remember that this is the value of a degree in the arts. It may not be as easily found in a surgical theatre or courtroom, but it is found in conversation with others, in creation, in debate. As long as there are women in these fields, there are also women to share its value. Ultimately, there is value in it yet. We must create the spaces ourselves for it to appreciate and be appreciated, and not concern ourselves with those who deem it useless.

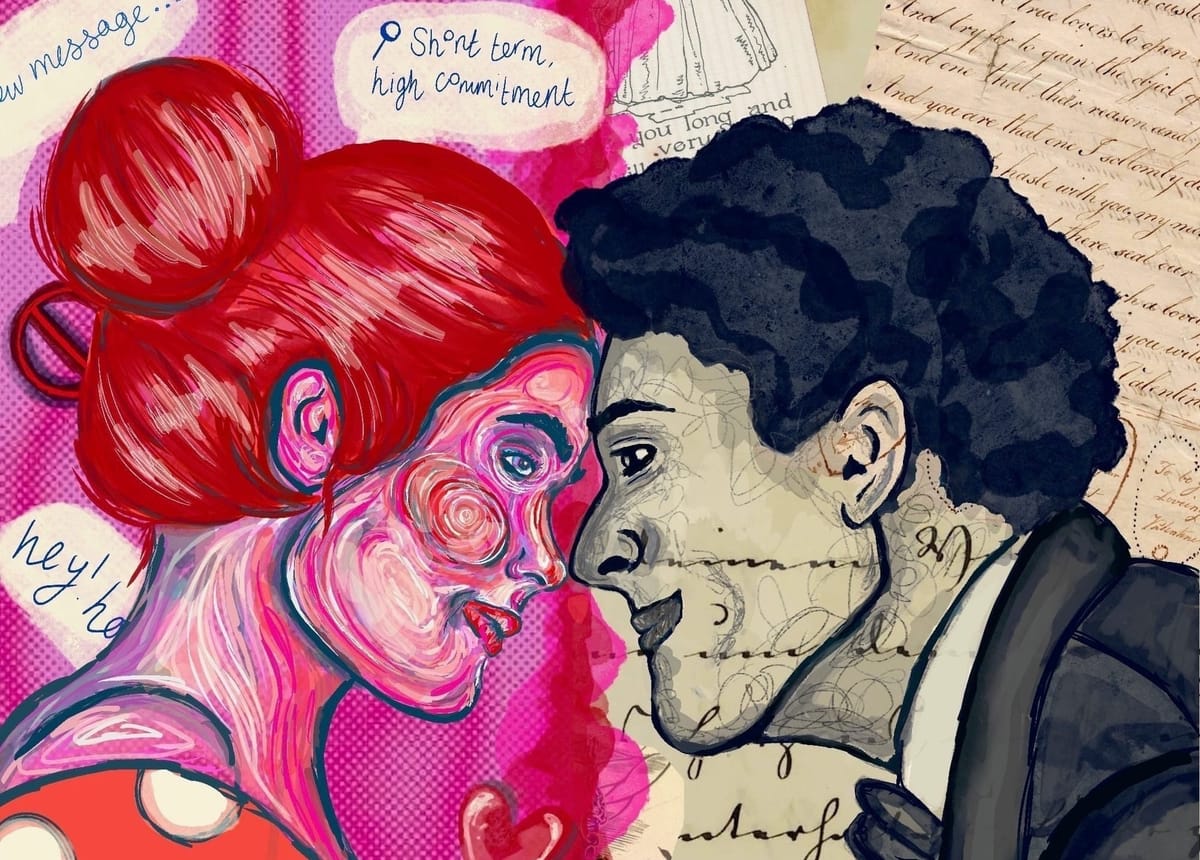

Featured image: Hugh Someya-Carr

Do you think arts degrees are valuable in today's world?