By Beth Astley, Second Year, Biomedical Sciences

After years of limited clinical research, University of Bristol researchers explore the link between self-harm and disordered eating in young people.

Self-harm and disordered eating are two of the most common consequences of mental health disorders across the globe and unfortunately often occur together. This is likely due to similar risk factors such as impulsivity, emotion disregulation and dissociation from psychological disorders.

A group of researchers from the University of Bristol have conducted a longitudinal study of 3384 females and 2326 males from a UK population, evaluated once at 16 years old and then a second time at 24 years old.

The researchers used a questionnaire which asked participants to report on their personal experience with disordered eating (which can include fasting, purging and binge eating among other things).

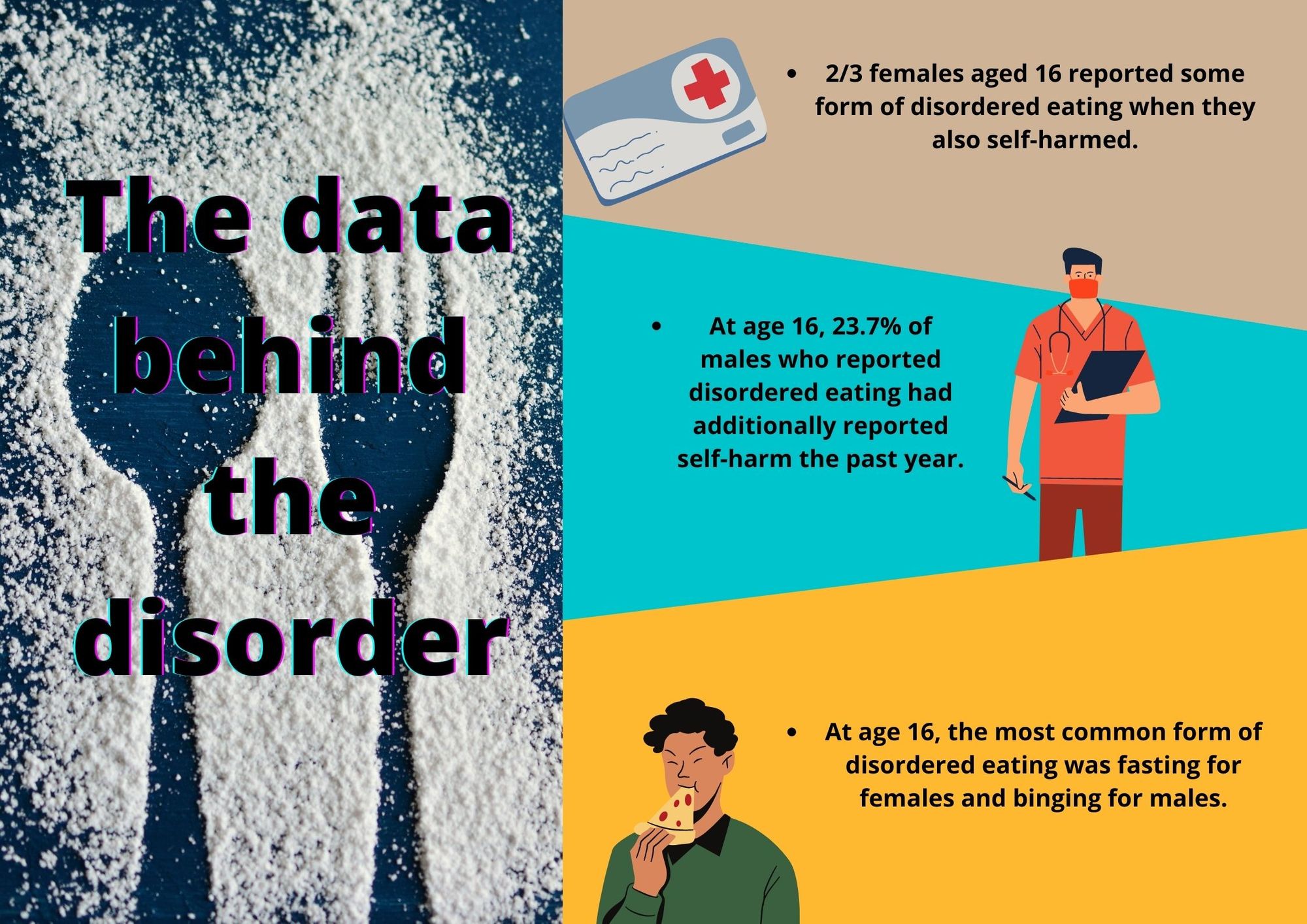

The study highlighted a large rate of comorbidity (the simultaneous presence of two or more medical conditions). Nearly two-thirds of females aged 16 and two-in-five 24-year-old males reporting some form of disordered eating when they also self-harmed.

Before 2021, most of the data collected on the comorbidity between self-harm and disordered eating had taken place in a clinical setting. Whilst this has been useful preliminary information, generalisation to the wider population has been difficult. This is because many of those with disordered eating and self-harm tendencies do not present to professional services or seek help.

Current Bristol research has opened pathways to understanding disordered eating

Therefore, current Bristol research which does not rely on clinical settings has opened pathways to understanding disordered eating. The most common form of disordered eating behaviour found in 16-year-old females was fasting, whereas binge eating was the most common behaviour in 16-year-old males and 24-year-old males and females.

At age 16 (of those that reported any disordered eating), 29.9 per cent of females and 23.7 per cent of males additionally reported self-harm in the past year. At the age of 24, these figures dropped to 16.1 per cent and 11.1 per cent respectively. This data collection was found to be consistent with previous research on the topic.

Future efforts should be put into place to encourage young people to come forward, and to increase awareness of indicators

However, despite the importance of this research, it does not come without flaws. While the study used a large, non-clinical sample unlike previous studies, more than 95 per cent of the participants were of white ethnicity.

This makes it difficult to generalise these findings to a wider population. Other demographics may have different, subtle symptoms that were not addressed in this questionnaire but are still significant.

Additionally, the study did not take into account participants who may define disordered eating as self-harm.

Eating Disorder Awareness week 2021: It’s time to shine a light on binge eating at university

Eating Disorders: a personal account

Despite this, the ground-breaking data has shed light to health professionals, raising awareness that this comorbidity exists. This study demonstrates that these behaviours can persist from late adolescence to early adulthood, and therefore future efforts should be put into place to encourage young people to come forward to services and to increase awareness of indicators.

This could help prevent those from developing this comorbidity between disordered eating and self-harm.

Featured Image: Epigram / Julia Riopelle (canva)

Warning: this is a sensitive topic.

If you or someone you know has been affected by any of the issues raised above, don’t be afraid to speak to a GP or contact charities such as Mind or Samaritans (call: 116 123).