By Julia Masluszczak, Arts Correspondent

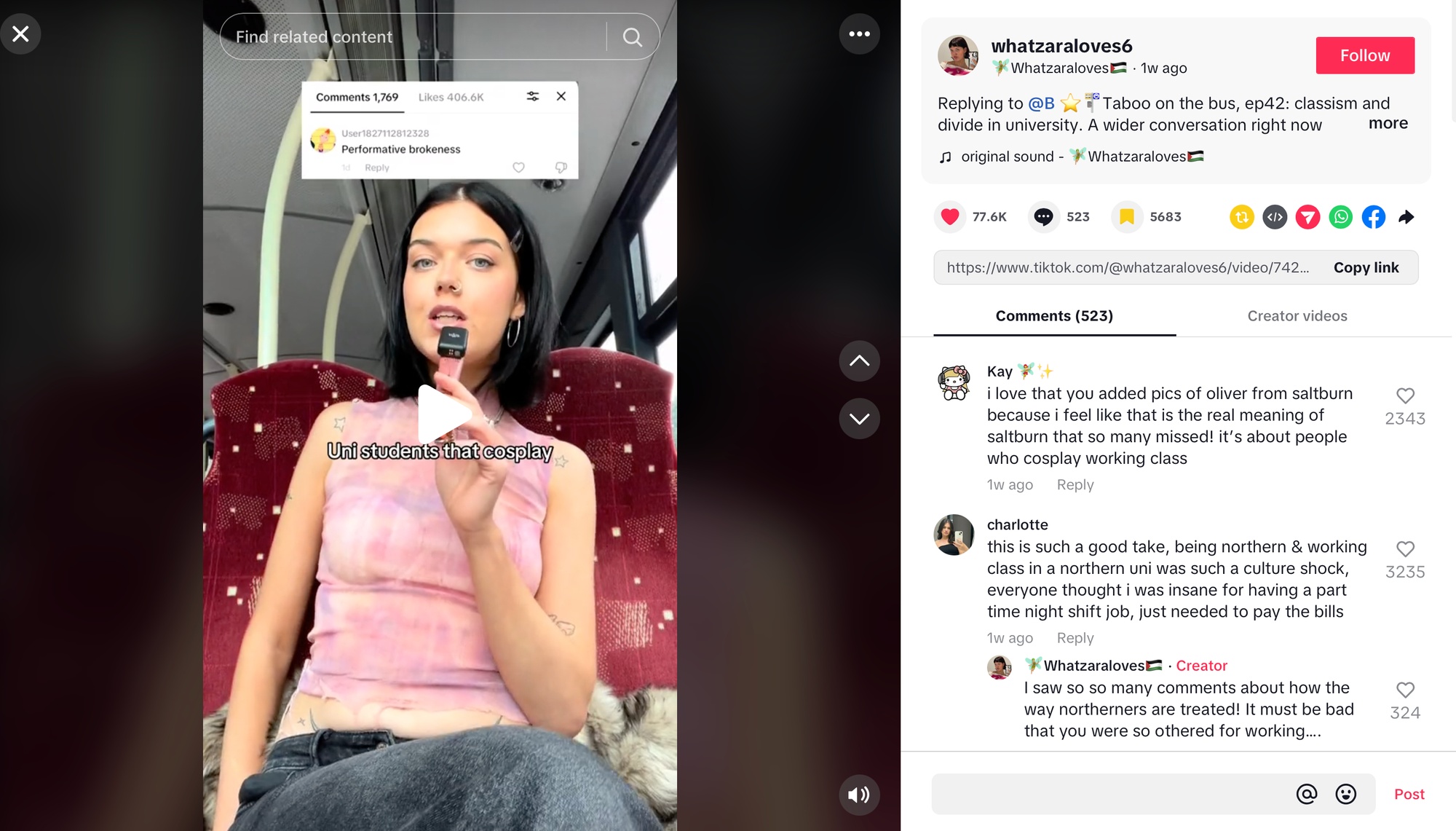

The recent controversy sparked by the Edinburgh Tab over the aesthetics of the posh and poor has raised important questions around classism and style. Their viral TikToks showcased university students' outfits, but commenters pointed out the conspicuous absence of Scottish students. When confronted, the Edinburgh Tab replied: "As god intended." This response, dripping with elitism, brings into sharp focus the class divides in academic spaces. But this isn't just an Edinburgh phenomenon—it also resonates here in Bristol, where the figure of the 'rah' girl epitomises class distinctions, particularly in fashion.

We all know what a ‘rah’ girl looks like, but if you want a detailed description, head to our recent article by Hannah Moser, ‘a ‘rah’ girl in her natural habitat: exploring the Bristol stereotype’ and you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. Basically, rah girls are often from wealthy backgrounds, known for their layered, eclectic fashion with scarves, jewellery, and tousled hair, usually all effortlessly thrown together in a perfect outfit.

Anyway, the ‘rah’ girl aesthetic isn’t just about high-end clothing and accessories; it’s a complex mix of luxury and deliberate shabbiness that has evolved over time. This tension between the posh and the poor has become particularly noticeable in recent fashion trends, where the style of the financially privileged often mimics elements traditionally associated with poverty. A perfect example is the frazzled Englishwoman vibe - look it up on Pinterest. What’s even more ironic is that these elements, rooted in economic necessity, are re-contextualised as fashion statements for the wealthy, further blurring the lines between necessity and choice.

At its core, fashion is an ever-evolving conversation about culture, identity, and status. But when trends that reflect poverty become chic, it raises an uncomfortable question: Are we fetishising poorness? From clothes to accessories, the aesthetic associated with the underprivileged has always been about making do—wearing old, used, or shabby items because there are no alternatives. What’s ironic is that these practical choices are now being replicated in the world of high fashion, where privileged individuals are paying premium prices for distressed or worn-looking clothing. You can even buy pre-worn shoes now - not pre-loved, but ones that have been broken in by someone and actually end up costing more.

Basically, the message seems to be that one can afford to look poor because one isn’t. And therein lies the paradox—people who struggle with financial insecurity don’t have the luxury of embracing ‘shabbiness’ for aesthetic value.

In Bristol, where wealth and poverty coexist, the rah girl aesthetic highlights this tension. While it claims to embody casual elegance, it often appropriates the "poor look"—vintage finds, skinny scarves, and worn-out shoes—raising questions about authenticity. Can we assert individuality when our privileged backgrounds shield us from real oppression? This disconnect from those they emulate is stark, as these carefully chosen items from charity shops and car boot sales come with inflated prices. Ultimately, this transformation of necessity into luxury underscores the class divide, turning the struggles of the less fortunate into a fashion statement for the privileged.

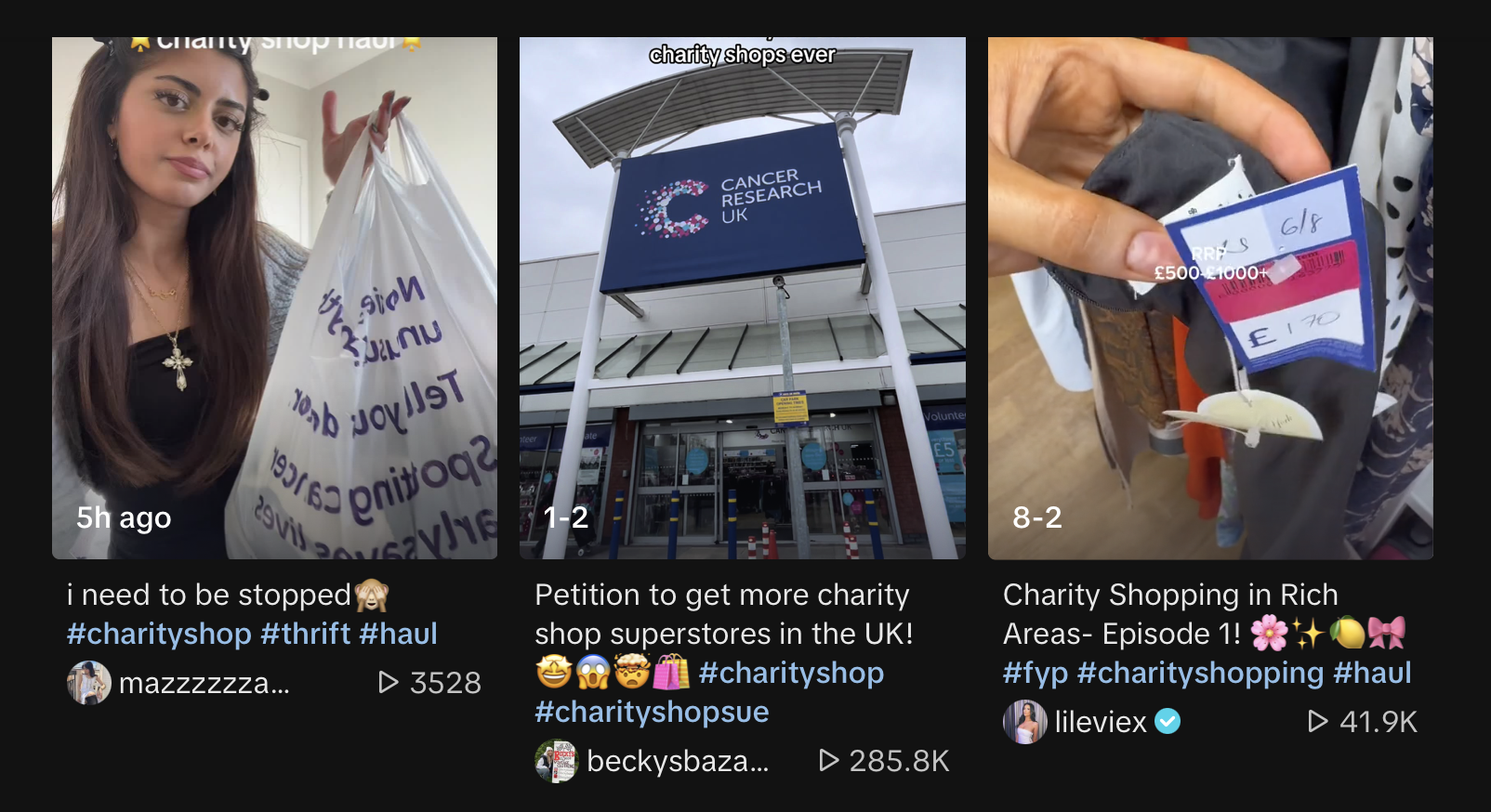

Charity shops, traditionally a lifeline for those in need of affordable clothing, are now catering to an entirely different clientele. According to the Charity Retail Association, charity shops saw a 15.1% increase in like-for-like store income between January and March 2023, compared to the same period in 2022. This spike isn’t due to an increase in economic hardship but to the rising popularity of vintage fashion, largely driven by wealthier consumers and by various TikTok trends.

While the demand for second-hand goods might seem like a win for sustainability and a fight against fast-fashion, it raises concerns about access. As charity shops become more popular among the middle and upper classes, prices rise, making it harder for those who truly need affordable options. And are we really criticising fast-fashion if we are also over-consuming second-hand goods? In this way, fashion trends not only appropriate the aesthetics of poverty but also limit the availability of resources for the people who rely on them.

As we critique these trends, it’s essential to question the ethics of fashion’s fascination with poverty. Are we celebrating resilience, or are we commodifying hardship? In a world where the line between wealth and poverty is increasingly blurred in the realm of aesthetics, we must be careful not to trivialise the realities of those who can’t afford to make ‘looking poor’ a choice. We could even go as far as to call it cultural appropriation.

As a little finishing note to our readers, this article is not intended to generalise or stereotype individuals into rigid categories of "posh" or "poor." We recognise that people's backgrounds, experiences, and identities are diverse and complex, and cannot be reduced to simplistic labels. Our discussion of fashion trends and aesthetics aims to highlight broader societal issues and dynamics, not to diminish or invalidate individual experiences.