By Freya Shaw, Creative Director

Epigram investigates the University of Bristol's problematic crest and whether it is time for a change.

When I accepted my place to study History in Bristol in the aftermath of the 2020 BLM movement, I was well aware that the city’s colonial history was resting heavily on its shoulders. Over time, I have become increasingly aware of the University’s complicity in supporting families who had active roles in the slave trade.

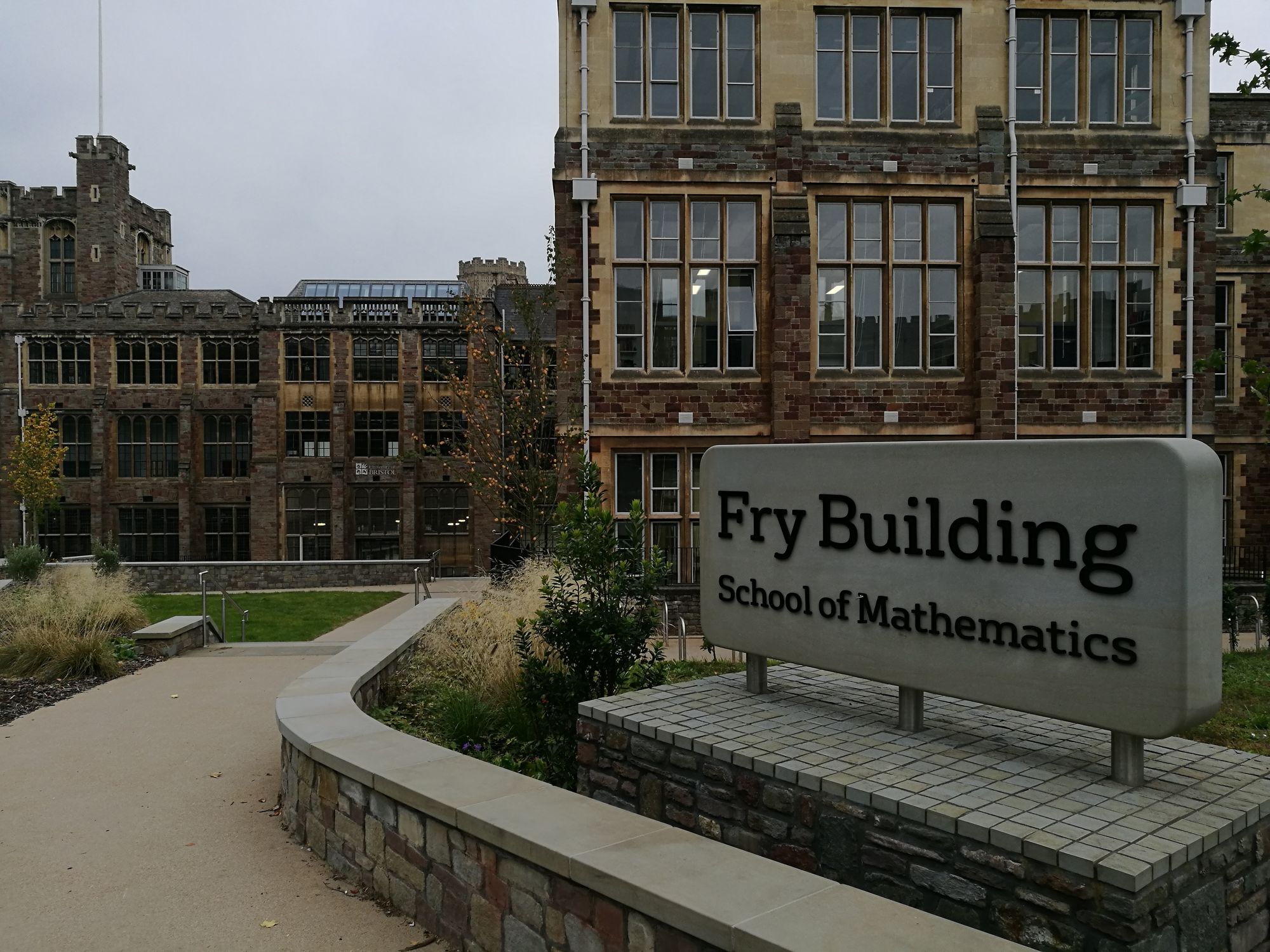

According to University’s estimates, 89 per cent of the wealth used to found the University was reliant on the labour of enslaved people. This funding, seen as charitable donations, enshrined colonial families in the institution's history, with many prominent and symbolic buildings being named in their honour; notable examples include the Fry Building and Wills Memorial Building.

These families were also bestowed the honour of visibility on the University Crest, which became the University logo as late as 2003. A sun for the Wills family, a dolphin for the Colston family, and a horse for the Fry family. Each family with their own colonial legacy through their direct participation in the slave trade.

The Colston family’s links to the slave trade are particularly infamous, owing to the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue in 2020. As deputy-governor of the Royal African Company, he was directly responsible for the enslavement of 84,000 people, 19,000 people of whom died in the Atlantic crossing.

In August 2021, ‘Colston Street Halls’ was renamed to ‘Accommodation Thirty-Three’, in an effort from the University to become an anti-racist organisation.

The second family to feature on the logo is the Fry family, who invented the world's first chocolate bar. The Frys' were responsible for 39 per cent of all cocoa imports from the Caribbean and its slave plantations. The family continued to exploit people even after the abolition of slavery in 1833, through enslaving people in countries where slavery was not yet illegal, like Sao Tomé.

Epigram spoke to Dr Richard Stone who, having spent 19 years at the University, is passionate about researching the economic legacies of slavery, particularly in relation to the University.

He explained the hypocrisy of the charitable donations of the Fry family who, despite being responsible for forced labour, were key figures in the Bristol abolitionist movement.

'You can't deny that he would have known what the conditions were like because he's read Equiano’s narrative. He's an abolitionist. He would have known buying all of these ingredients is propping up slavery, and yet he's still being actively, knowingly complicit in it, which is really, really complicated.'

Finally, the Wills family were tobacco manufacturers who owned slave plantations in the US despite Slavery being abolished in the UK. The Wills family is perhaps the most visibly commemorated family in the structure of the University today with the iconic Wills Memorial Building named after the University’s first chancellor, Henry Overton Wills III, whose donations are claimed to have made the institution possible.

This begs the question, do the actions of these families truly represent the current institution as we see it today? What role should the University play in educating its population on the dark side of its past? And more crucially, what should be done about the University logo?

Demands for Bristol University to address its colonial history are not new. In 2017, ‘Past Matters’, a project lead by Dr Stone, organised a petition to change the name of Wills Memorial Building. This petition gained 692 signatures and divided Bristolians, with a counter petition appearing in reaction. At the time, the University commented to Epigram that ‘It is important to retain these names as a reflection of our history.’

In 2020, Epigram met up with Asher Websdale and Shakeel Taylor-Camara, students involved in the ‘Past Matters’ project, who stated, ‘The biggest issue is that people that oppose these movements really struggle to understand what memorialisation is. There are many ways we can memorialise without paying homage to any of these people.’

Since 2020, the University has stated that they have ‘Made a commitment to review the logo which is part of a wider project looking at our brand identity.’ A request for an updated statement from the University in October 2022 was greeted with a reiteration of this ‘commitment’.

However, according to Dr Stone, change is imminent: ‘I don't know what we'll see. It's important that this is based on consultation and discussion. It needs to be a back and forth talking to people and engagement with people.

‘Everyone should feel welcome in university. And if you have these difficult histories and you're trying to push them under the carpet, intentionally or not, you create a barrier for some people.

The crest is present in all University branding: every official document and email is smeared with this colonial reminder. Logos are visual brand reputations, thus leading us to question why the University appears to be validating individuals who were directly accountable for profiting from human exploitation.

'Our relationship with the past shouldn't be fixed in time, it should be

shaped by the values of the current generation and actually what we care about, what we value.'

Dr Stone agrees: ‘For me, 20 years is quite a long lifespan for a brand. So I think it's time for the University to rebrand, to change a lot of its graphics. And it's part of a natural process that our relationship with the past shouldn't be fixed in time [...] We always need to be mindful of the past, but equally we really need to look to the present and the future as well.’

The past is not static, and in order for the University to be brought in to the modern, anti-racist institution it professes it is, the logo should be changed. The fact that until recently I, and many others, were unaware of the colonial links in the logo speaks to how normalised the University’s colonial history is.

Dr Stone notes that we miss the colonial nature of the logo because it's ‘Hidden in plain sight: A lot of these things don’t look like [...] they're connected to slavery. And that's a big part of the problem. So, one of the things we need to do is train people to look critically, to think critically, and to alter the way people think about things.’

Often, those who argue against a change will claim that if we keep these symbols of the slave trade, it will educate people. Even if this were true, I don't see how this would educate people more effectively than a change itself. Moreover, if a modern, controversial figure, linked to the suffering of hundreds of thousands, was memorialised in this way on the basis of ‘education’, serious questions would be raised. So why do we not hold older, institutional logos to this standard?

The University of Bristol would not be the first Bristol academic institution to change the logo in the aims of reassessing the colonial narrative. The Dolphin School in Montpelier designed a new image in March 2021 as the dolphin was likened to the crest of the Colston family. This change was not an erasure of history. Instead, it redirected the historical narrative into one that does not glorify the profits of the slave trade.

Throughout my investigation, it’s become clear that a change is needed. This is crucial, not just for the legacy of the University itself but also for the students and staff, who deserve more than to be represented in this antiquated, immoral way.

Do you think the University of Bristol should change its logo?