By Harry Stringer, Third Year, Classics

Transgender characters have existed on the periphery of all manner of media. But in recent years, portrayals of trans characters that are more positive, more accurate and ultimately more diverse have become increasingly more common.

Lacking the understanding of gender identity and dysphoria that we possess today, trans identity has often been conflated with different concepts like cross-dressing and sexual role play. Even though most older media does not explicitly depict trans characters, the films and television series that depicted this amalgamation of ‘gender confusion’ nevertheless would have influenced the public perception of trans people.

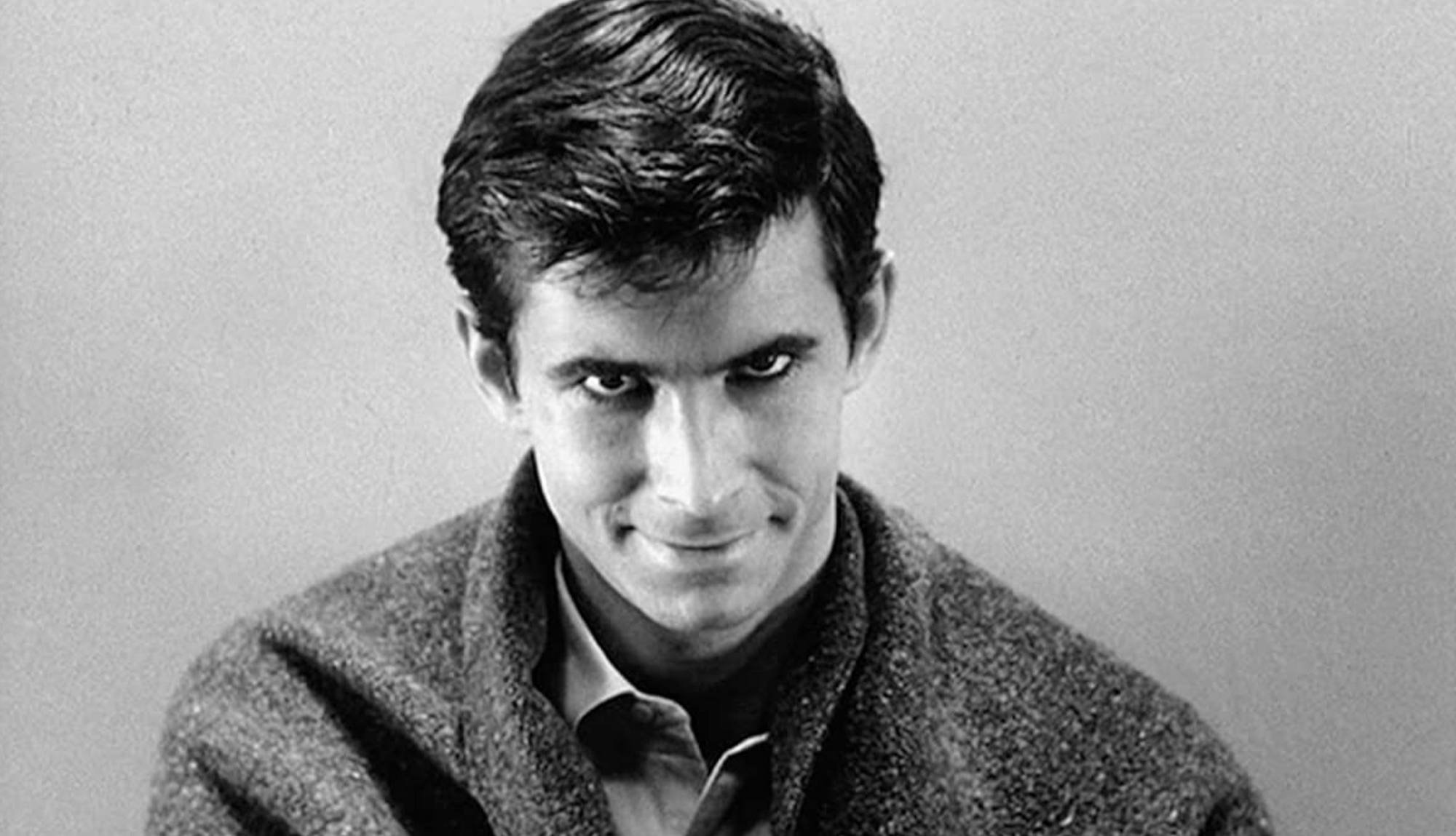

Many have noted a distinct correlation between ‘gender-confused men’ and perverted serial killers like Norman Bates of Psycho (1960), who commits murder in the dissociative identity of his deceased mother, and Jame Gumb from The Silence of the Lambs (1991), who kidnaps women so that he can make a female-presenting suit out of their skin.

Neither of these characters are actually transgender (in fact, Gumb is explicitly stated not to be) and yet to some, these murderers and trans women are grouped together as ‘men who fantasise about being women,’ damaging the perception nevertheless.

Trans representation in media should attempt to portray the realities of the historical and current trans experience, both positive and negative

This is the case despite the reality that trans people are far more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators of it according to statistics from ONS. This brings us to another harmful trope: transgender characters are portrayed as the victims of violence in 40% of their depictions on screen, according to a study by GLAAD.

A notable example of this is Boys Don’t Cry (1999), one of the few high-profile stories of trans men, which tells the true story of the rape and murder of Brandon Teena. Meanwhile, trans women often appear as victims of horrific crimes, often murdered sex workers in crime procedurals like CSI (2000-2015). These depictions are not wholly misguided as they do draw attention to a genuine issue. However, there is a risk that seeing the stories of trans people constantly end in tragedy sets a dire expectation.

That is not to say that trans representation in media should not involve depictions of prejudice as it is, unfortunately, an almost inherent part of the current trans experience, but rather that it should depict joy and unity also.

An example that walks this line is Pose (2018-), set in the ballroom scene of 80s/90s New York, a subculture where black and Latinx LGBT+ people, subject to the brunt of society’s prejudice and rejected by their birth parents, would form substitute families in the form of ‘houses’ and compete in ‘balls’ by walking the runway dressed for categories like ‘executive realness’ and ‘royalty’, drawing heavily from the seminal documentary Paris is Burning (1990).

Cisgender homosexuals and drag queens were also prominent in the scene but the series puts transgender women in the spotlight, featuring five trans women of colour playing major characters in its ensemble cast. Pose does not shy away from the dark underbelly of LGBT+ history, depicting brutal violence, poverty, the effects of HIV and prejudice in all its forms.

Furthermore, it does not hesitate to show some of the prejudice within the community with gay people discriminating against trans people, white LGBT+ people against those of colour and trans women who pass well against those who don’t. However, it also depicts the support and love of one’s ‘chosen family’ against their shared adversity. As one of the house mothers, Elektra, says after her estranged house daughters come to her aid in a time of need: ‘We may cut each other up like a pack of alley cats, but when the outside world tries to tear us down, this army closes ranks.’

Through this duality, Pose both educates the mainstream audience about trans history and transphobia but does not doom them to a life of tragedy. Of course, it is not perfect: the fact that the modern-day actresses pass so well does not quite capture the difficulties of being trans at the time without the same access to medical resources and narratively, problems have a tendency to be solved almost as soon as they arise. But, overall it is a vast improvement from earlier depictions.

As art imitates life, trans representation in media should attempt to portray the realities of the historical and current trans experience, both positive and negative. However, as life also imitates art, perhaps there is space for another kind of transgender representation. When the members of various houses dress up as executives and monarchs in the kind of balls we see in Pose, they are not representing their reality but rather an elaborate performance of their aspirations, unattainable to most but forever hoped for. Perhaps it is the aspirational spirit of the balls that will pervade the next generation of trans representation.

Shows like Netflix’s She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (2018-2020) seem to be moving in that direction, with several trans or otherwise gender nonconforming characters, already revolutionary in a children’s series, who effectively exist in a post-gender world. The representation is there but their gender identity is never an issue of contention.

How fiction tells the stories history won't

World Mental Health Day: how should mental illness be explored in cinema

We ought to turn our gaze beyond western media and to, for example, Japanese anime which is often far less conservative in its depiction of gender nonconformity. Granted, it possesses its own harmful tropes such as the ‘trap’ – passing trans women who are fetishised for their supposed capacity to deceitfully cast male heterosexuality into jeopardy, and the ‘okama’ – a grotesque caricature of effeminate gay men, drag queens and trans women, all conflated under one label.

What these two examples share is a tendency towards the otherworldly. Indeed, supernatural and science-fiction genres, in which gender can be changed as easily as clothes, or fantasy worlds, which lack our history of prejudice, seem the natural home for these more aspirational trans stories and it is to these that we should turn for the next step in trans representation.

Featured: IMDb

What are your favourite films and TV shows that feature transgender characters?