By Anonymous

The Croft Magazine // An anonymous student sheds light on the realities of drug-taking and mental health.

I am an ordinary teenager and come from an ordinary background. My experience with drugs and mental health are not extraordinary.

I never experienced problems with mental health throughout my childhood and early teenage years. I had a standard upbringing and by the time GCSEs came around I was happy, healthy and enjoying life. I smoked weed and drank alcohol on occasion but not in excess.

I tried a harder drug when I took MDMA during the summer after GCSEs at a music festival - very cliché, I know. I took it three nights in a row and became obsessed with the euphoria it gave me. I ended up taking it every month from September until December.

The drug was perfect for my work hard, play hard lifestyle and so after my exams my MDMA consumption increased; I took it about six times in four weeks, ignorant of its long-term effects. Regardless, I got stellar exam results and by the end of my lower sixth year summer life could not have been better.

But if you’re using MDMA to hold your life together it is bound to come crashing down. My first bout of anxiety was at the start of upper sixth when my teacher told me that my personal statement was below par. I lay on my bed and worried that I was stupid and bound to be a failure and for the next four days I had all the symptoms of flu: body temperature fluctuation, nausea, exhaustion, headaches, you name it.

The possibility that this was caused by anxiety never ran through my mind; I did not even know what anxiety was. After five days my older brother told me to go and see my teacher and when I reluctantly did, my teacher explained how to improve and my flu literally disappeared. I assumed that what had just happened was a blip, so I carried on with my life as it was.

I had the mindset that if no one told me that I seemed different, I was getting good grades, and my friends were still friends with me, things were fine

The rest of upper sixth was mundane. I was depleted from the drugs and although my anxiety was manageable, my interest in hobbies and life in general had evaporated and I mindlessly floated about. I resorted to what I knew best and used drugs to provide the dopamine and serotonin that my body longed for. I’d smoke weed up to five times a week and it soon became my main source of happiness.

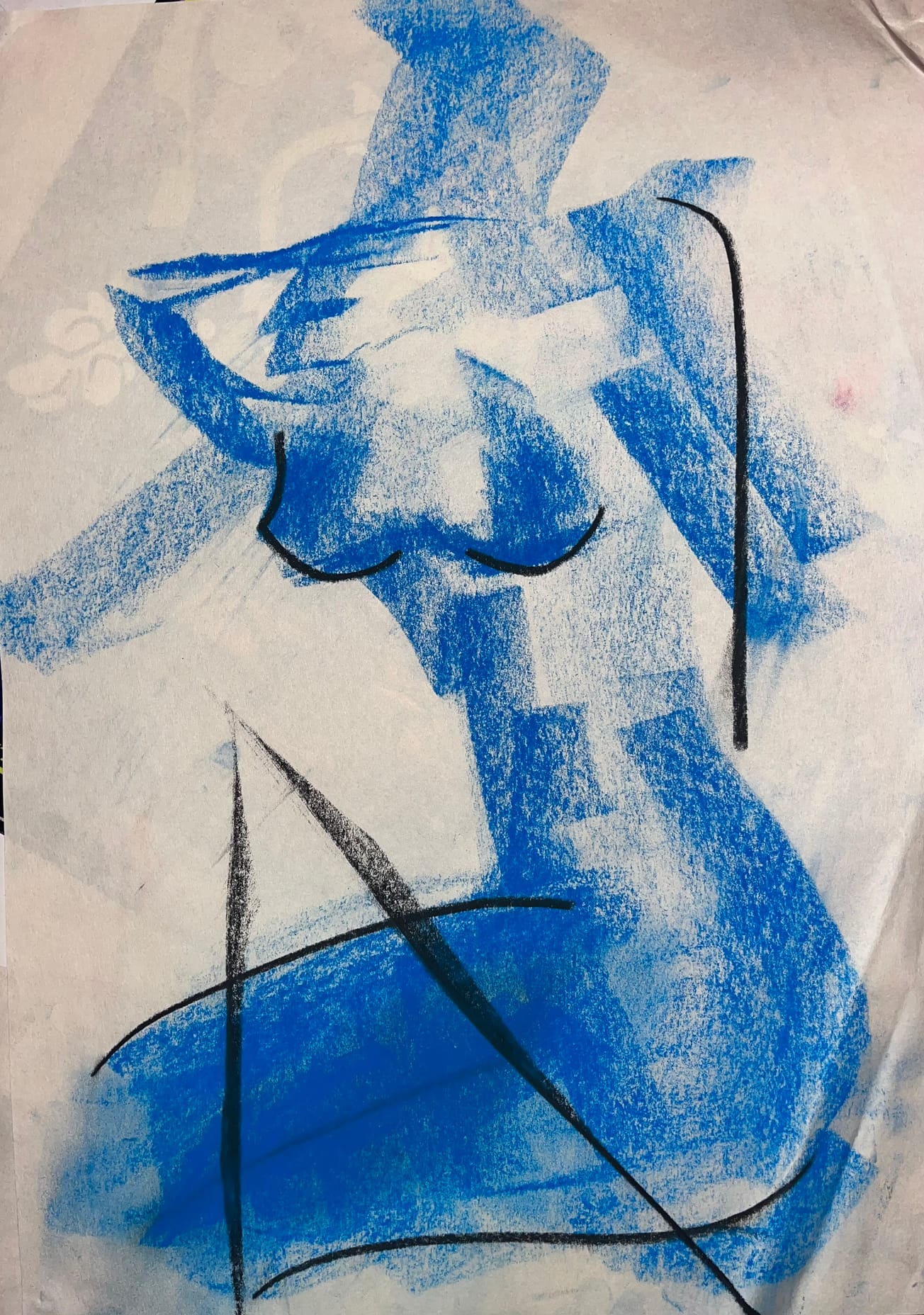

Life was blue but I had the mindset that if no one told me that I seemed different, I was getting good grades, and my friends were still friends with me, things were fine. There were countless red flags that year but I didn’t have the skillset to pick up on even the most blatant evidence.

A Level exam season arrived and a month before my exams I was smacked to the ground by a tsunami of crippling anxiety. I had been stressed since revision had started, but my anxiety intensified from a three to a nine on the Richter scale when I woke up in the night before my Geography mock. It was 3am, my right leg was twitching uncontrollably, I was out of breath and reciting a case study on the Akosombo Dam, listing every bloody detail I knew about it. As you may have guessed, I didn’t get back to sleep.

I had begun my descent into a dark abyss. From that point until exams, every minute I was awake I worried about any thought, regardless of how unimportant it was. It could have been something rude that I had said to someone when I was 13, but I would fret about it for hours, sometimes even days.

I struggled to maintain even the most basic conversation without finding the most trivial detail to dissect and worry about. Productive work would last for about 10 minutes at a stretch, because as soon as the first concern entered my mind it was game over – from that point until the end of the day I was utterly unproductive. As I picked up new worries throughout the day my anxiety intensified until around 4pm, when I’d acquire my daily migraine, and had to give up my futile battle against my overwhelmingly powerful arch nemesis.

I would wake up every day at 4 a.m. feeling incredibly distressed, and worries would immediately storm my mind like a burglar invading an unarmed property – from that point there was no chance of me getting back to sleep. Without sleep, I was more vulnerable to anxiety and so I would desperately try get back to sleep till 8am. By the third week I had memorized every sound so that I knew exactly what time it was: 4.30 was when the birds started tweeting, 5.15 was when the sun would rise, 6.45 was when I would hear my dad getting ready for the day… when I would finally get up I’d feel like I was going to vomit and could not eat until the evening. Every day was an emotional roller-coaster and I wanted to burst into tears by the evening. I was clueless about how to deal with these issues and none of my friends could give me good advice.

When I finished my exams my anxiety immediately improved, so I blocked out what had happened since I felt frightened and humiliated that I could be unwell. Fortunately, my anxiety only affected me occasionally through the summer. But it was waiting to lash out when I started university. The prospect of a new life far away from home was enough for my anxiety to recommence its attack, but I tried my best to avoid it. I did all I could to fit in, no longer interested in excelling. I found people I got on with and stuck with them. I was not interested in working hard or doing extracurriculars, I was solely interested in minimizing my worries.

Ironically, living such a mundane life only worsened my mental health and when I got back to university after Christmas, I felt increasingly lonely, lost and despondent. I constantly questioned whether I had any friends: I felt like no one liked me and thought that everyone was judging me, and since drugs had played a big part in my life for the past two years and I resorted to them to suppress my issues.

I’d go out most days of the week and do as many drugs as possible, be it MDMA, Cocaine, Ketamine, Xanax; I became increasingly reliant on Xanax, which seemed like a godsend since it magically wiped away all my problems and made me feel like I was the king of the world. I was high on it once for five days straight.

It’s so common for peers to assume that someone who abuses drugs is just a fun-loving hedonist but underneath there is often a cry for help

Not only did I act like an idiot, but the days after were intensely sobering. My food, my bedroom, the grass, everything, was the blandest, most mind-numbing grey I have ever seen. That term, my average day consisted of ordering takeaway to my room, skipping seminars, spending hours playing PlayStation, smoking weed to pass the time and going to bed when the sun rose. I had no goals, no intentions, no meaning. My sole task was to get to the end of the day.

I knew deep down that the drugs were serving an ulterior motive, but I was confused and lost, and they were the easiest way to deal with my problems, especially because everyone around me was taking them too. I floated through term and no one around me suspected a thing – they just thought I loved getting high. It’s so common for peers to assume that someone who abuses drugs is just a fun-loving hedonist but underneath there is often a cry for help. As I took more drugs, I did less with my life and my mental health further deteriorated, which I responded to by doing more drugs… nonetheless, I finished the year with a 2:1 and superficially it seemed I was doing fine!

During the summer holidays I came to the conclusion that something was wrong, but I was oblivious as how to improve. I refused to accept that I could have mental health issues since I always had the fearful perception that illnesses like anxiety and depression indicated that someone was fragile and feeble. Nonetheless, I was determined to live a more meaningful life than I had in the previous year and the most obvious step I could take was to become healthier.

I had been living an unhealthy life for the past few years and knew that even if this was not the key to solving my problems, it would certainly help. This involved doing less drugs, getting up earlier, working harder, going to the gym and having a daily routine. Within months I was significantly happier and more confident.

Yet I was still anxious most of the time and my continual attempt to ignore this prevented more substantial improvements. During the third week of second year I went into freak-out mode about my coursework and all the symptoms I had during A Level revision came back. It felt like I had just run head-first into the same brick wall that I had crashed into before; it was particularly dejecting since I’d thought I was on the mend.

At that point I wanted to give up on university and my aspirations and strive for a simpler life. I thought to myself, If I feel like this every time I try to do anything slightly complex, what is the point in carrying on? What was the point in trying if every time I worked on something, I suddenly became distressed and lost all capability to be productive?

vocalising my worries helped me understand what was going on in my mind

Fortunately, every cloud has a silver lining and this episode convinced me to begin searching for a therapist. I dished up 800 pounds of savings and saw a few until I found one that I got along with. I kept the whole therapist situation a secret since I still felt embarrassed about it. I had never spoken about my anxiety and vocalising my worries helped me understand what was going on in my mind and the extent to which it affected me. My therapist taught me practical techniques about how to tackle, rationalise and be positive about anxious thoughts and I soon noticed significant improvements. After a few months I could look my anxiety in the eyes and overpower it.

Even though I had accepted my anxiety I was still ashamed of it, but I knew that my parents deserved to know what was going on. As I confessed my darkest secrets to them I felt humiliated, weak and emasculated even though they had supported me since day one. I had never spoken to my parents about my problems and I couldn’t help but feel like I had failed them. Unsurprisingly, it turned out that talking to them was integral as even though they didn’t fully understand, they reassured me that they were proud of me no matter what. This helped me feel more willing to deal with my anxiety and I could then make hastier improvements. Furthermore, I became less disappointed in myself when I got anxious and I was happier to talk about it with my friends.

I have been significantly happier in the past year thanks to living a more fulfilling life and dealing with my anxiety. I have stopped doing drugs and I am sure that this has improved my anxiety and general wellbeing; stopping drugs was not easy but not as hard as I expected.

Although I am better at dealing with my anxiety, I still don’t always sleep well, and I still have bad days and weeks. However, I have learned to be positive even when I am having the worst of days and to tackle my problems immediately rather than letting them grow. I am sure that I am only going to get better at dealing with negative thoughts.

If you feel like something is not quite right, even if you aren’t certain what is wrong, speak to someone you can trust

We are suffering from a mental health epidemic. I imagine that there are so many people out there, particularly boys, who are suffering from similar or much worse problems than the ones I had and refuse to accept this. The stigma around mental health is still very much alive and a lot of people still judge each other about it – I don’t feel comfortable talking about my mental health with a lot of my male friends.

Drug abuse is a common cause of and exacerbator to mental health issues. I can’t stress anything more than if you want to do drugs, educate yourself on them so that you know the sensible amount to take and how often you should take them. Be aware of how much and how often you are taking them and whether you are doing it in moderation.

Make sure your friends are doing fine and be there to listen to them – listening to a friend’s problem can be all it takes to improve their day. However a desire to change has to be made of your own accord.

If you feel like something is not quite right, even if you aren’t certain what is wrong, speak to someone you can trust. This could be a therapist, a close friend, or a parent. Once you talk about your problems you can understand them better and tackle them more effectively. It’s a slow process but things do improve.